In early 1565, five ships commanded by Miguel López de Legazpi and navigated along a course plotted by Andrés de Urdaneta reached the Philippines after a three-month journey from Barra de Navidad, Jalisco. The tornaviaje, or return route, was even more difficult, since due to prevailing winds and currents, their previous route was impossible. Instead, they opted to head north towards Japan to make use of what would later be termed the Kuroshio Current, and by this means sail across to California, and thence down the coast to Mexico.

It was an amazing feat of seamanship and set the stage for what would become the first global trade route, one made possible by the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade, which, for 250 years, saw Asian silks, spices, gems and porcelain traded for Mexican silver. These yearly galleon ships, or Nao de China as they were known in Mexico, were laden with rich cargo and thus were immensely important to the Spanish imperial economy. Of course, they were also highly attractive to English pirates, or, as they were known during times of war, privateers.

Cabo San Lucas, a haven for pirate attacks

Amazingly, two of the four successful pirate attacks against Manila Galleons during the centuries-long trade occurred in Cabo San Lucas. Amazing, because there were no permanent settlements anywhere on the Baja California peninsula when the trade began during the 16th century. Only Indigenous populations. So, why here?

The route from Manila to Acapulco took longer, so crews suffered from scurvy and often ran low on water when their stores ran out and they couldn’t collect enough rainwater. The solution to both maladies was a stop at San José del Cabo, to replenish water at the freshwater estuary, and feast on local fare. Indeed, for nearly the entirety of the 250-year galleon trade, what is now known as Los Cabos was a stop-off point. The battles with pirates or privateers took place in Cabo San Lucas Bay because the half-mile Land’s End headland provided perfect cover for them to lie in wait, and a handy hill (the 500-foot Cerro del Vigía) on which to post a lookout.

Cavendish takes an epic prize

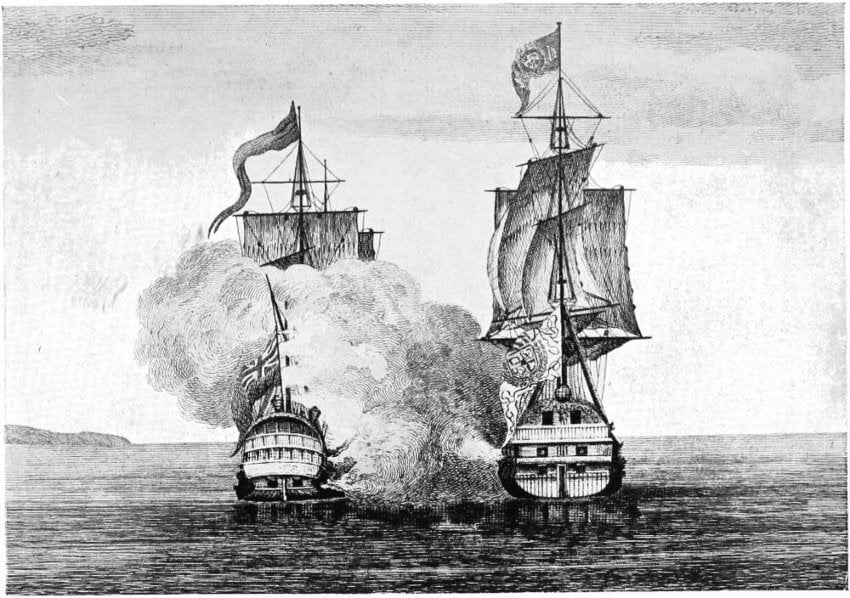

The galleon Santa Ana was four months out of Manila when she was sighted by English privateers led by Thomas Cavendish aboard two vessels, Her Majesty’s Ships (HMS) Desire and Content, in November 1587. The battle that would follow in Cabo San Lucas Bay was an epic one, lasting nearly six hours. The galleon was much larger — in the range of 600 tons, as compared to the 80-ton Content and the 120-ton Desire — but the smaller ships were more maneuverable, and during hand-to-hand fighting with swords and bucklers, the English discovered they had another advantage. During a previous visit to Acapulco, Santa Ana’s cannons had been commandeered to protect the fort.

Santa Ana was thus defenseless for the bombardment that followed, as the English stood off and pounded the ship and her crew of 160, with a barrage of cannonfire. Once the Santa Ana was compromised and began to sink, Captain Tomás de Alzola surrendered her and the treasure was offloaded into the holds of the two English ships. It was an immense haul, 122,000 pesos in gold and booty worth nearly two million pesos in total. To put this amount in perspective in modern terms is impossible, except to say that it amounted to approximately 10% of the annual Spanish imperial budget for itself and its far-flung colonies.

If sending ships this valuable on long sea voyages seemed an enormous gamble, understand, writes Arturo Giraldez in “The Age of Trade: The Manila Galleon and the Dawn of the Global Economy,” that trade during this era was highly speculative and highly volatile, and that a “single ship was capable of making a difference in the value of goods or altering the price of bullion in a particular market.”

Cavendish, meanwhile, sailed back to England aboard Desire to be knighted by Queen Elizabeth. Content, which was separated from Desire immediately after leaving Cabo San Lucas, was never seen again and has been the source of more than 400 years of lost treasure rumors in Los Cabos.

Woodes Rogers and Robinson Crusoe capture another galleon

Over 120 years would separate the first successful capture of a Manila Galleon and the second. What these two attacks had in common, of course, was that both took place in Cabo San Lucas Bay and were instigated by English belligerents. The difference was that Woodes Rogers, captain of the British ships Duke, Duchess and Marquis that would attack the Manila galleons in 1709 — yes, there were two that year — was a pirate, not a privateer, as Spain and England were, for a change, not at war at that time.

Rogers had plenty of time to get ready, as after rescuing Alexander Selkirk, the inspiration for Robinson Crusoe, from a remote Pacific island, he and his crew spent two months in Cabo San Lucas waiting and getting to know the Indigenous Pericú. Finally, in December, they sighted the Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación y Desengaño, which had been separated from her sister ship en route, and whose guns had been placed in the hold to make room for more cargo. It was thus easy pickings for the pirates, who helped themselves to the immense treasure (170,000 English pounds worth) after a brief engagement during which 20 Spanish sailors and nine British were killed.

Rogers took a musket ball to the jaw during the fighting, and when the sister ship Begoña arrived days later, fully armed and ready for combat, he was injured again in an unsuccessful attempt to capture her, too. Still, it was a successful mission and a well-heeled crew who returned to England with the Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación y Desengaño, renamed the Bachelor, in tow.

Buccaneer days in old Los Cabos

Those weren’t the only attempts made by English sailors to capture the Nao de China, nor was England the only country hell-bent on loosening Spain’s colonial grip in the Americas by harassing Spanish ships, including those transiting via Los Cabos. French pirates also made raids in what is now Baja California Sur during the 17th century, and Dutch sailors were seen in the vicinity during the following century, although there is no evidence of them engaging in piracy.

Not that this more legal approach paid very good dividends. The Dutch ship Hervating famously anchored in 1746 off San José del Cabo, in its San Bernabé Bay, with hopes of trading with the Jesuit missionaries who had been there for over a decade. The Jesuits were game, writes author Harry W. Crosby in “Antigua California,” despite the Spanish ban on such trade. However, when the padres sent an emissary to the mainland to smooth the way for further trade, he was tortured and the Dutch ship that had followed in his wake was turned away, with its landing parties beaten back by force.

Thus, in the pirate annals of Los Cabos, while it wasn’t always the British who opposed the Spanish, it was they who proved the most enduring and obdurate foes. The last example of this occurred in 1822 and was somewhat unusual since it happened one year after Mexico had gained its independence from Spain, and the British commanders were serving a different nation than their native one.

Lord Cochrane’s fleet sacks San José del Cabo

Lord Thomas Cochrane, the dashing British aristocrat and naval hero who inspired literary creations like Horatio Hornblower and Jack Aubry, was finishing up a stint as vice admiral of the Chilean navy in its fight for independence from Spain in 1822 and seeking to sweep the Pacific clean of any remaining Spanish ships when he arrived with his fleet in Acapulco in February 1822.

That same month, two British captains under his command, William Wilkinson aboard the Independencia and Robert Simpson on the Araucano, sacked and looted the now Dominican mission at San José del Cabo, on the pretext that it still flew the Spanish flag. The Baja California peninsula was so remote at this point that it’s possible the friars didn’t know the war had ended five months earlier. In any case, there was no excuse for the banditry and destruction that followed, first at San José del Cabo, then later at Todos Santos and Loreto. Except that such depredations are the calling cards of pirates everywhere, even those who fly the flags of nations instead of a skull and crossbones.

The good news for Los Cabos, although no one knew it then, was that after nearly three centuries of piratical incursions, there would be no more, save a few scattered filibustering attempts later in the 19th century. Now, in the 21st century, the only pirate ships in local waters are those operated by tour companies, and the simulated sword fights are merely entertainment between cocktails and helpings at the buffet.

Chris Sands is the Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best, writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook and a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily.