The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is pausing avocado inspections in Michoacán following what it called an unsafe incident in a rural part of the state involving two American inspectors.

Michoacán is Mexico’s No. 1 avocado producer and exporter.

The pause in Michoacán avocado inspections also applies to mangoes grown in the state. Michoacán is Mexico’s second largest exporter state of mangoes to the U.S., according to the Mexican Association of Mango Producers and Exporters (EMEX). Michoacán was responsible for 19% of the 65.3 million cases of mangoes exported to the United States in 2023.

In conjunction with the announcement about the pause in avocado inspections, the U.S. State Department issued a travel alert stating, “Due to recent security incidents in Aranza, Michoacán, the U.S. government reminds U.S. citizens not to travel to the state.”

It restated that its current travel advisory for Michoacán is “Level 4 — Do Not Travel due to crime and kidnapping.”

The USDA’s red light on inspections in the state means the import into the United States of Michoacán’s “green gold” — as avocados from the state are often referred to — will be limited to items that have already undergone inspection or are currently in transit.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said Tuesday that a “sane solution is being sought … but it takes time.”

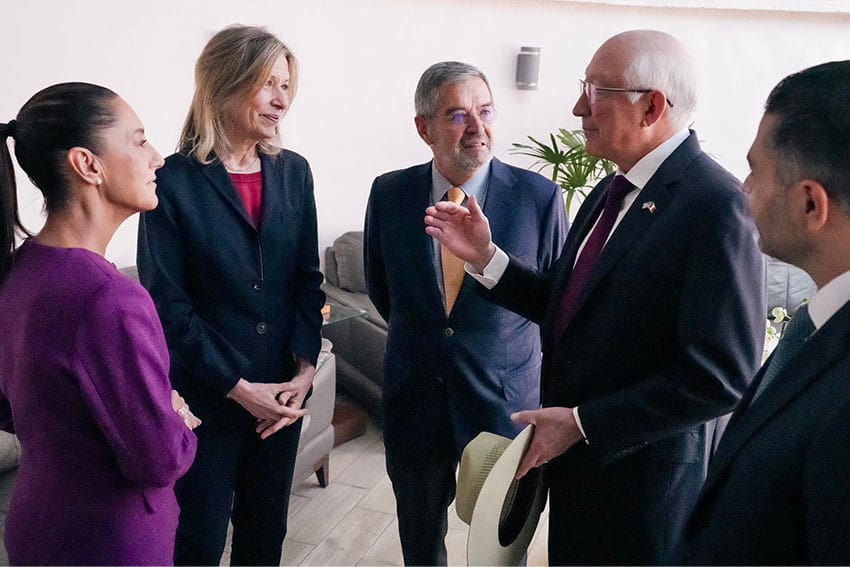

In a post on the X social media platform on Tuesday, U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Ken Salazar confirmed that the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) had suspended inspections in Michoacán “until these safety issues have been resolved.”

“This pause does not affect other Mexican states, where APHIS inspections continue,” Salazar added. “This action does not block all exports of avocados or mangoes to the United States, nor does it stop products currently in transit.”

Salazar wrote that two APHIS employees “were recently attacked and detained while carrying out their work in the state of Michoacán inspecting avocados,” adding, “They are no longer in captivity.”

The incident reportedly occurred Friday during a blockade by community members in Aranza, a town in the municipality of Paracho. However, Michoacán Governor Alfredo Ramírez Bedolla disagreed with Salazar’s version and other published accounts of the incident.

Ramirez told the Ciro Gómez Leyva news radio program that the “two agents were never at any risk.” However, the newspaper El País wrote that Aranza community members “detained and beat” the two inspectors.

Bedolla agreed that some private vehicles were stopped during a “social demonstration,” including the one in which the inspectors were traveling. However, he said it was not due to their role as inspectors and that they were not physically harmed or harassed.

He did concede that the inspectors might have “felt attacked,” as might anyone when their car is “detained.”

Bedolla also expressed confidence Tuesday morning that the conflict over avocado inspections could be resolved within the next 48 hours — a stance that was seemingly contradicted by Ambassador Salazar’s post on X shortly thereafter.

“Next week, I will travel to Michoacán to meet with [Bedolla] and the Association of Producers and Export Packers of Mexico (APEAN) to address, among other important issues, security,” Salazar wrote.

Of the U.S. decision to pause Michoacán inspections, President López Obrador said, “Well, those are their policies. Fortunately, we have good relations [with the U.S., and] we are convincing them to act differently, but it takes time.”

According to El País, the U.S. imported 1.4 million tonnes of avocados from Mexico last year, a 17% increase over 2022. More than 80% of the avocados produced in Mexico are exported to the U.S. Overall avocado production in Mexico this year is predicted to be 2.7 million tonnes, with 73% of that total coming from Michoacán.

The United States also halted Michoacán avocado inspections twice in 2022, also for safety concerns.

The first suspension occurred after a Uruapan-based inspector received a threatening call to his official cell phone; the second was implemented due to violence in Michoacán, one of six Mexican states categorized as “do not travel to” by the U.S. State Department.

With reports from Infobae, El País, Forbes and New York Times