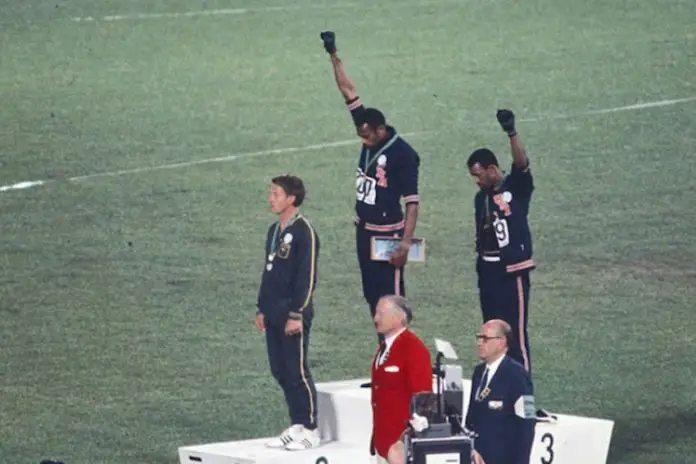

When it comes to politics, many in Mexico remember the 1968 Olympics primarily as a focal point of the student movement of that year, which culminated in the Tlatelolco Massacre days before the start of the games. The Olympics, which the International Olympic Committee (IOC) intended to remain apolitical, might have offered a quiet ending to the fiasco. Instead, they became the scene of John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s iconic Black Power salute, one of the most famous political statements ever made in sports. A response to racism across the world, the salute was not a spontaneous gesture but the brainchild of one man: Dr. Harry Edwards.

A former student athlete, in the mid-1960s Edwards was not only a 6-foot-8 giant of a man but a distinguished sociologist writing on race and sport, who had played basketball and could hurl the discus 200 feet. In 1967, he was teaching at San Jose State University: in September, Edwards led a protest movement against racist discrimination on campus, adding pressure to their demands by organizing a boycott of the season’s first football game by Black athletes. In October, this initiative grew into the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). Track and field stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos were two of the organization’s early members.

The OPHR’s list of demands included restoring the heavyweight title Muhammad Ali had lost protesting the Vietnam War and the resignation of International Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage, who had defended the Nazis and sought to bar women from the games. Disinviting apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia from the Olympics was the central demand, adding the OPHR to the 32-country boycott against the Mexico City games.

The leverage behind these demands would be the threat of America’s Black athletes boycotting the 1968 Olympics. “For years we have participated in the Olympic Games, carrying the U.S. on our backs with our victories, and race relations are worse now than ever,” Edwards said at a meeting on the boycott. “It’s time for the Black people to stand up as men and women and refuse to be utilized as performing animals.”

However, as the 1968 track season built up momentum and athletes got a taste for competing, Edwards felt his hopes of an Olympic boycott fading. The wind further went out of the boycott’s sails when the IOC maintained South Africa’s expulsion from the Olympics.

On the night of April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. In the tense weeks that followed, a group of Black athletes at University of Texas El Paso decided to boycott a track meet at Brigham Young University in protest of what they saw as the Mormon church’s racist teachings. Eight of the nine African-Americans on the team — including the young long-jump sensation Bob Beamon — refused to travel. They expected a reprimand but instead had their scholarships withdrawn. For his part, Bob Beamon was confident of his post-Olympic future and took it in his giant stride. But for the rest this was a shattering blow, making clear that any protests would carry a heavy price.

The potential Olympic team spent the summer in the high-altitude training camp at Echo Summit, California. Pumped and confident, nobody was considering boycotting. However, the idea of making some sort of protest at the Olympics had not been dismissed, although no one could agree on what form it should take. The athletes got on the plane to Mexico still uncertain of what lay ahead.

The 100-meter final, staged on day two of the track and field program, would be the first test for the protesters. A demonstration was never likely. Six-time NCAA champion Charlie Greene was the most militant of the three American representatives in the final, but was aware that his two colleges would not support him. Mel Pender was an active-duty military officer who could not make a political gesture. Jim Hines, who had just become the first man to sprint 100 meters in under 10 seconds, would not protest either. When Hines and Greene received their medals they stood quietly for the national anthem. It was one-nil to Avery Brundage and the IOC.

Two days later Tommie Smith and John Carlos took gold and bronze in the 200 meters and raised the Black Power salute on the Olympic podium. The next day, the two athletes were marched out of the Olympic compound by security guards. News of the expulsions broke slowly and attention was still centered on the track, where Willie Davenport took the men’s 110 hurdles title. Davenport had military connections and dreams of a football career. He and silver medalist Ervin Hall stood respectfully on the podium.

Yet as news of the draconian treatment of Smith and Carlos spread through the Olympic village, the mood darkened. African-American athletes forgot the demands of the OPHR: they were now protesting the treatment of their teammates. Vince Matthews, a member of the 4×400 relay team, wrote “Down with Brundage” on a bedsheet and hung it from his apartment window.

The Black athletes had support from many white colleagues but the U.S. team was divided on the issue. Coach Hank Iba ordered his basketball players not to get involved. When rower Paul Hoffman gave a boxer a protest button, a coach threatened him with physical violence.

The next test of their athlete’s resolve would come with the 400 meters final, where the clear favorite, Lee Evans, was a college teammate of Carlos and Smith. As the competitors were warming up for the big race, Bob Beamon stepped onto the long jump runway. Described as uncoachable, some pundits were predicting that Beamon would break the world record in Mexico. Others thought that his ragged style would end in three no-jumps.

Beamon was fast on the runaway and for once hit the board perfectly. He gained freakish height to his leap and his long, long legs stretched out in front of him; he bounced forward, balanced.

Then came the moment of farce. Mexico had installed the most modern measuring equipment, an optical device that slid along on a rail until it was level with the correct mark in the sand. But the device had not been designed to roll out this far. A steel tape was produced and the jump was measured the old-fashioned way. Fifteen minutes passed. Then the scoreboard shows 8.90: Beamon had just set a world record that would last for 23 years.

The evening finished with the medal presentations. The long jumpers were first up and neither Beamon nor bronze medalist Ralph Boston were considered militants. The team came out on the podium in long black socks. Boston took it even further, appearing barefoot. This was how angry the athletes had become. “Now they’re going to have to send me home too,” he commented afterwards. But despite the gesture, both men stood respectfully for the national anthem and in doing so walked an unclear line.

U.S. officials denied this was a demonstration and the IOC let the gesture slide.

The 400-meter awards followed and would be a greater test. The U.S. had won all three medals and Lee Evans, Larry James and Ron Freeman came out in the black berets associated with the Black Panthers. They wore long black socks. But when the national anthem sounded they removed the berets and stood quiet. The intellectual Evans handled the attention of the press. Asked why he had worn the beret, Evans responded that it was raining. Reporters noted that Smith and Carlos had been taciturn, whereas Evans and the others had smiled: “It’s harder to shoot a guy who’s smiling,” Evans replied.

The 400-meter men had made a protest of sorts, but the IOC did not press the issue. Their actions however, did not please everybody in the Black community. Certainly not Evans’s colleagues back at San Jose, who were angry with him for letting Carlos and Smith down. Certainly not his wife, who left Mexico and flew home before the relays.

Athlete protests in Mexico City soon faded out. When George Foreman won the heavyweight boxing title he paraded around the ring with an American flag. The basketball team won the country’s seventh consecutive title and celebrated with smiles and waves. It was as if events in the main stadium were happening in another world. But it was Smith and Carlos’s gesture that had marked the Olympics forever and changed American society more than anybody at the time suspected.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.