As part of an exploration into Mexico’s long and rich history, Mexico News Daily has teamed up with one of the country’s top Maya experts to examine the ancient world that flourished across Mesoamerica. This is Part 4 in a series of articles on the ancient Maya. Follow the links to read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

In our previous entry, we talked about how the Late Classic period for the pre-Columbian Maya was characterized by a high degree of political maneuvering and military aggression, leading to increased political and social complexity.

Hence the need for this second article on the Maya Late Classic period — continuing our previous installment. Re-read the first part here.

There’s a lot we’re not certain of, but as we mentioned in the previous article, evidence suggests that the Maya societies during this period were involved in an escalating struggle to control natural resources, the procurement of luxury materials and the dominance of trade routes to guarantee the procurement of said luxury materials, and to generally accumulate wealth and power.

Who were the Kanu’l dynasty?

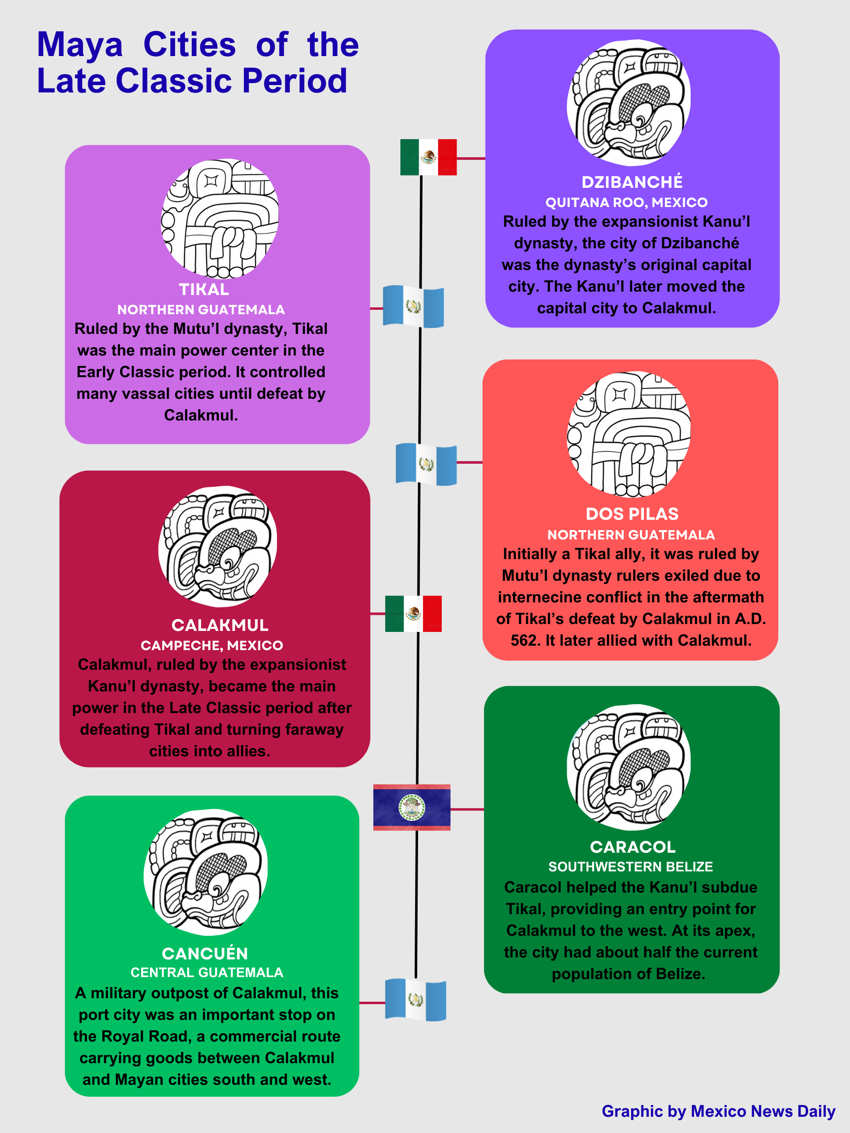

As we mentioned in Part 2 of our series, during much of the Early Classic period, the dominant power in the Maya Lowlands appears to have been the political entity of Tikal, in Guatemala, and its ruling dynasty, the Mutu’l. This dominance followed the defeat of nearby rivals like the city of Uaxactún, as well as the linking of the Mutu’l with foreigners arriving from Teotihuacan — an event we also discussed in Part 2. These Teotihuacan outsiders imposed a new geopolitical reality in Mesoamerica during the Early Classic period and possibly took Tikal as their primary center.

However, we know from an artifact from the Mesoamerican city of Caracol in Belize — referred to as Altar 21 — that Tikal’s forces were defeated in A.D. 562 when Caracol allied with a new force hailing from the distant northern lands: the Kanu’l dynasty, who were from the city of Dzibanché in Quintana Roo and used a distinctive emblem glyph featuring a snake’s head.

During the sixth century, Dzinbanché had begun an aggressive territorial expansion strategy that took them to both northwestern Mexico and southward into Belize and Guatemala’s Petén region. A clash with Tikal, the greatest power in the Petén, was inevitable.

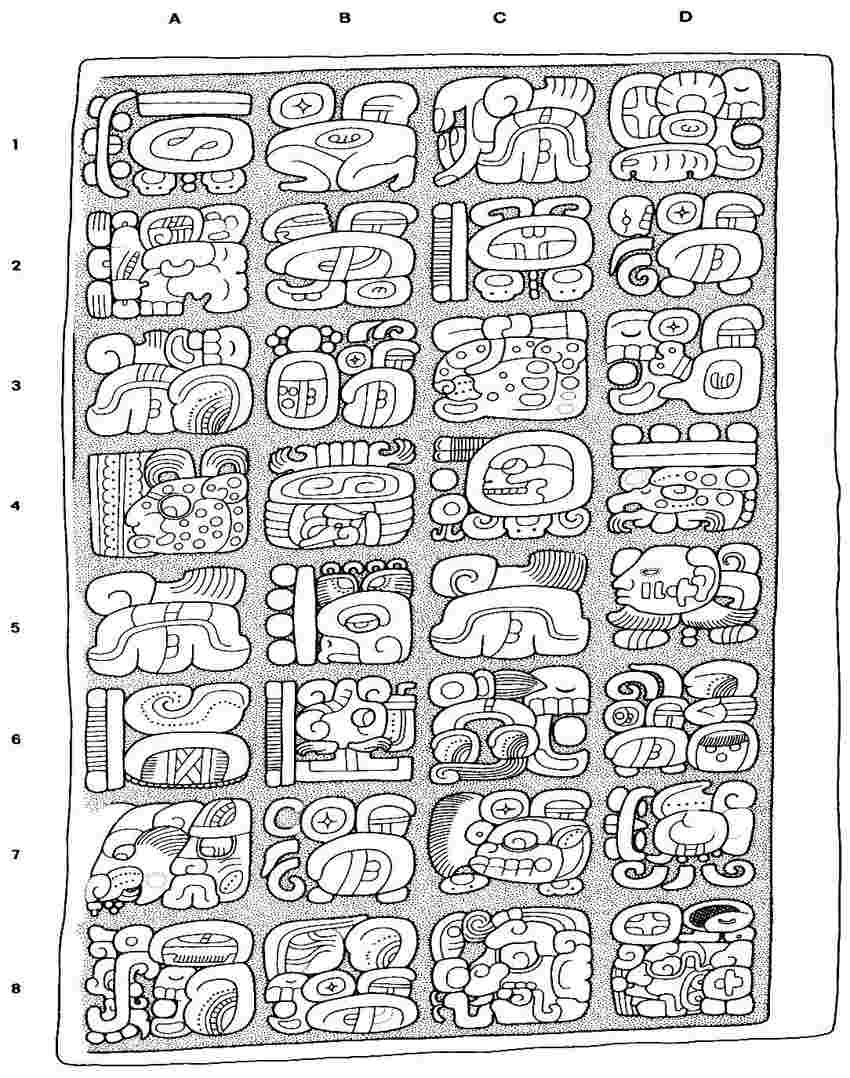

One piece of evidence Dzinbanché’s aggressive expansion can be found in an archeological artifact known as Lintel 35, from the Mesoamerican city of Yaxchilán, in modern-day Chiapas.

Carvings on the lintel recount how, during an armed conflict in A.D. 537, Yaxchilán’s rulers — the Pa’chan dynasty — captured an important war captain of the Kanu’l dynasty and sacrificed him to the city’s patron deities, evidence that Dzibanché’s rulers were rapidly expanding their power and influence.

Likewise, several stelae found in Naranjo — a city located in the Guatemalan Petén near Tikal and Caracol — explain that by A.D. 546, Naranjo’s rulers had already been allies of the Kanu’l dynasty for several generations.

This territorial expansion allowed Dzinbanché to gain control of two key routes: the Usumacinta River in the northwest and the Belize River and its tributaries — whose northern outlet reached as far as Chetumal and whose southern outlet facilitated communication with cities like Naranjo and Caracol. This control also provided a gateway to conquering the west and Tikal.

And so the conflict of A.D. 562 thus signified the collapse of the Mutu’l dynasty as a major power in the region — at least for the moment — and the rise of the Kanu’l dynasty, with its growing network of allies.

Dzinbanché becomes Calakmul

Multiple stone monuments from the beginning of the seventh century record the presence of Kanu’l rulers in different cities across the Maya Lowlands and their military imposition on sites as important as Palenque in Chiapas.

Around A.D. 635, following an interdynastic conflict, the Kanu’l dynasty decided to move its capital from Dzibanché to Calakmul, in present-day Campeche.

The great city of Calakmul — whose ancient name was Uxte’tuun (“the city of the three stones”) — enjoyed a privileged, central strategic location. Its position allowed it to control communications in all directions and establish trade routes to the west, east and south. With the appointment of Yuhkno’m Ch’e’n II as Calakmul’s new ruler around A.D. 636, the Kanu’l dynasty experienced its golden age, establishing a vast network of favorable alliances.

This ruler established what is known as the Camino Real (Royal Road), a communication route reaching the city of Cancuén in Guatemala, which allowed Calakmul to control the important Pasión River, through which various objects and products reached the capital.

Yuhkno’m Ch’e’n II began remodeling Calakmul, erecting several monuments and building its most important pyramidal structures. He also expanded the Kanu’l dynasty’s dominance: Many of the new k’uhul ajaw (holy lords) of other cities owed him fealty, as they had been installed into office in the presence of the ruler himself, who authorized and legitimized them.

Tikal’s loss is Calakmul’s gain

During Yuhkno’m Ch’e’n II’s reign — and until his death in A.D. 686 — the defeated city of Tikal and its leaders suffered submission to the Kanu’l, who closely monitored Tikal’s actions. In this regard, the Kanu’l leaders’ involvement in the internal conflict between two factions of the Tikal dynasty — as noted in the hieroglyphic record in the ancient city of Dos Pilas — is noteworthy.

Located in the Petexbatún region, near the Pasión River, the city became a key enclave to which a section of the Mutu’l dynasty in Tikal was exiled, possibly for advocating a closer relationship with the Kanu’l — possibly under the influence of Calakmul’s leaders. What we do know is that Dos Pilas integrated into Calakmul’s network of allies after the internal dynastic conflict in Tikal.

How Calakmul controlled its vassal cities

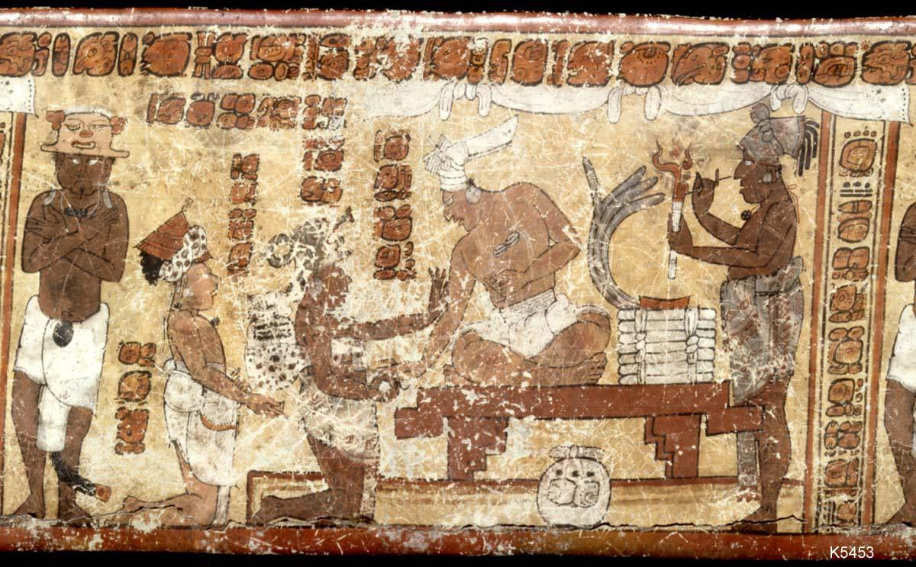

Although Calakmul’s network of vassal dynasties maintained a degree of political autonomy in their lordships, the Kanu’l rulers imposed a subtle yet firm control over their subordinates through marriage connections and by raising political hostages.

Yuhkno’m Ch’e’n II and his successors, Yuhkno’m Yihch’aak K’ahk’ and Yuhkno’m Took’ K’awiil, maintained a strategic marriage policy, sending elite daughters to various cities to marry future rulers and thus establish favorable alliances. In addition, hieroglyphic inscriptions also reveal cases where firstborn sons and future young rulers were sent to Calakmul to learn the ways of courtly life while being groomed as loyal future allies. Both of these strategies have been recorded at the site of La Corona in Guatemala.

A Tikal resurgence and the end of the Kanu’l dynasty

Although Yuhkno’m Ch’e’n II’s successors worked to maintain the Kanu’l dynasty’s power — representing themselves as the great rulers of both the earthly and supernatural planes who had the favor of a large number of deity patron entities that certified their authority — around A.D. 695, Calakmul’s network of allies and its control system began to crumble.

With Yuhkno’m Ch’e’n II’s death in A.D. 686, Tikal’s leaders began to reorganize: Ruler Jasaw Chan K’awiil strengthened his city’s position in the region to the point where he received emissaries from Calakmul at his court to negotiate. No agreement was reached, however, and in A.D. 695, the armies of the two most powerful dynasties in the Maya Lowlands clashed.

The confrontation was decisive, as was the defeat of the Kanu’l dynasty. Calakmul lost one of its most important patron deities, Yajaw Man, on the battlefield, taken back to Tikal as war booty. Gradually, the Kanu’l’s old network of allies became scattered as Tikal — under Jasaw Chan K’awiil and then his son, Yihk’in Chan K’awiil — continued to reconquer nearby territories.

The Kanu’l leadership — with Calakmul now a vassal state to Tikal — understandably made constant attempts to project a sense of normalcy: Yuhkno’m Took’ K’awiil ordered the remodeling of buildings and the erection of new stone monuments exalting the dynasty and its ruler — who bore the most important political titles, was accompanied by preeminent supernatural entities and was adorned as a prominent military chief.

However, the reality was different: A few years later, around A.D. 736, Tikal attacked again at the outskirts of the capital city. Ruler Yuhkno’m Took’ K’awiil was defeated and captured.

We do not truly know his fate, but he was likely taken to Tikal to be exposed to public derision alongside one of his captured patron entities. Perhaps he was fortunate enough to return to Calakmul. But a potential portrait of him carved on Altar 9 at Tikal — showing a man captured and bound — suggests a tragic end for the last of the Yuhkno’m rulers of Calakmul.

With Calakmul defeated, Tikal’s victorious ruler was not benevolent: He launched a series of attacks against former Kanu’l allies, such as the cities of Naranjo and El Perú-Waka’, subjugating Tikal’s longtime adversaries.

Despite the situation, Calakmul’s leadership made valiant efforts to maintain the political and social order in their city. But by the end of the eighth century, the dynasty’s sunset was an undeniable reality, and the Kanu’l rulers eventually disappeared from the archaeological record.

During this period, we know that the occupation of Calakmul dropped significantly, as did the construction of monuments and buildings. The great Kanu’l city slowly and irrevocably lost its splendor.

Pablo Mumary holds a doctorate in Mesoamerican studies from UNAM and currently works at the Center for Maya Studies at IIFL-UNAM as a full-time associate researcher. He specializes in the study of the lordships of the Maya Lowlands of the Classic period.