I was recently talking to a Mexican friend about people whose work defined our respective countries. Other friends trotted out the usual suspects – “William Shakespeare,” “Winston Churchill,” “Isembard Kingdom Brunel” and so on. When it was his turn to think of some notable Mexicans, my friend began with the same somewhat tired list; Benito Juárez, Emiliano Zapata and Diego Rivera. Then he turned to me and said “Did you know a Mexican wrote ‘The Blue Danube?’”

I didn’t, and that was partly because he turned out to be incorrect. It turns out that while Mexican authorship of “Blue Danube” is something of a common misconception in Mexico, the song he was referring to is arguably even more recognized than Johann Strauss’ Viennese waltz.

You actually already know the song. It plays at the circus, at the sports game, the carnival, in movies and even in video games like “Forza Horizon.” The tune has become synonymous with good old-fashioned leisure, but its composer and an enormous influence on U.S. folk genres remain relatively unknown, even in his home country.

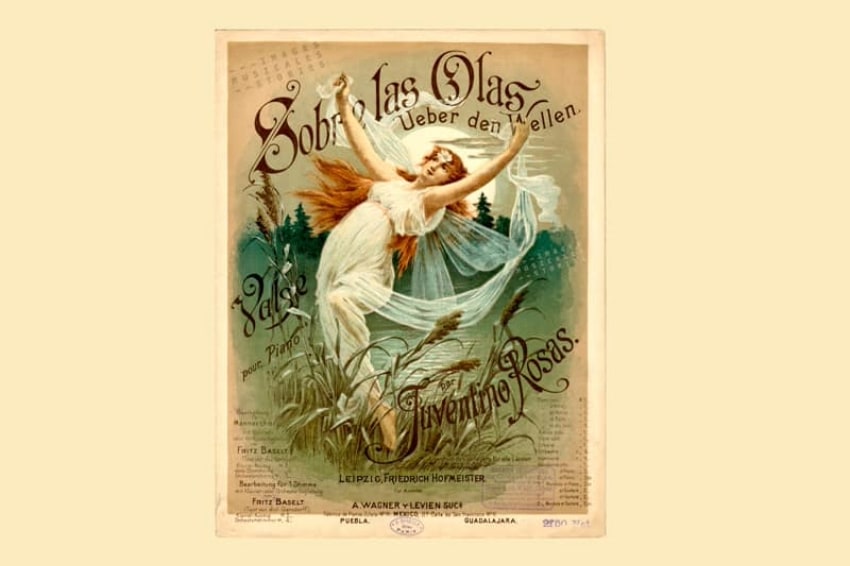

“Sobre las olas” was composed by Juventino Policarpo Rosas Cadenas back in 1888 and is more than the soundtrack to a daring trapeze routine. After experiencing a revival in the mid-20th century, the song has become a mainstay of classical music and New Orleans jazz, country, bluegrass and tejano – many of the more traditional U.S. and Mexican folk genres.

Juventino Rosas: Mexico’s most important classical composer

Born in Santa Cruz, Guanajuato – now Santa Cruz de Juventino Rosas, for reasons that will become obvious – in 1868, Rosas began his career as many aspiring musicians have: on the street. Joining up with a dance band in Mexico City, the young Otomí composer and his family walked the 180 miles from their hometown to what was then the Mexico City suburb of Tepito when Juventino was just seven years old.

Success very quickly followed the young violinist, and by 18, he had performed for legendary opera singer Angela Peralta – the “Mexican Nightingale” – and for President Porfirío Díaz. Despite these enormous achievements, young Rosas had an uneasy relationship with the formal musical establishment, dropping out of the city’s conservatory twice before taking any formal exams.

By the end of the 1880s, the now-teenaged Rosas toured with a military band, finding himself in Michoacán. A few years later, he was further north still, working in Monterrey. Here, Rosas joined a touring band, traveling through the U.S. on his way to perform at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

Death and success

The World’s Fair gig was high profile enough to land Rosas a job traveling Cuba with an international crew of musicians. Sadly, he contracted spinal myelitis while touring the island and succumbed to the infection shortly afterward, aged only 26. He was buried in Cuba but his remains were later repatriated to Mexico in 1909. Thanks to his posthumous stardom, Rosas was buried in the Panteón Civil de Dolores cemetery in the prestigious Circle of Illustrious Persons, next to presidents, artists and revolutionary heroes.

He published 25 compositions in his lifetime – mostly Mexican danzas and European waltzes, almost entirely through the Mexican publishing house Wagner y Levien. “Sobre las olas” itself was sold for a mere 45 pesos – though it reportedly made its new owner hundreds of thousands when it became a fixture of the European waltz scene.

“Sobre las olas” did not make much of a splash in Rosas’s lifetime. However, in the early part of the 20th Century, the song exploded in popularity.

Author José Emilio Pacheco once remarked, “Only one other waltz vies with the ‘Blue Danube’ for the privilege of being played around the world every day, every hour. It is ‘Sobre las olas’, the best-known musical composition among those produced by the Mexican arts.”

“Sobre las olas,” George Lewis and Americana

While the song became a smash hit on the European and Latin Waltz circuits, its life in the early 20th century is still more remarkable. The evolution of U.S. southern folk genres – particularly New Orleans Jazz, Tejano, Bluegrass, and Country and Western – owes Rosas a significant debt, and the song became a mainstay for musicians across the country.

While other traditional Mexican songs often formed part of early jazz repertoire – notably “Cielito Lindo” and “La Bamba” – none has been elevated to the status of Rosas’ magnum opus.

While it is well known as the classic crooning track “The Most Wonderful Night of the Year,” it is New Orleans Jazz where the song became most notable. Jazz scholar Paul Tighe explains how the song became so symbolic of early jazz that British audiences actually wept when first hearing it performed.

The song was closely associated with legendary jazzman George Lewis – a man who had supposedly never left New Orleans and was, therefore one of the purist players of the genre. His rendition of “Sobre las olas” was now tied to the legend that he had recorded it while recovering from an attack in a hospital in 1943.

“The pedestal that this song was placed on shows it was a major part of the set and is identified with Lewis as early as 1943,” he explains.

“When he toured Britain in 1957, when people saw him – when people heard him for the first time, people wept because they thought they were hearing the essence of New Orleans Jazz,” Tighe continues. “The song remained prominent in his live performances until his death in 1968.”

This was 80 years after Rosas first published the song, which had taken on a new life. The adoption of “Sobre las olas” was actually part of a wider trend of Latin music entering the U.S. cultural sphere. According to Tighe, legendary Jelly Roll Morton – one of the progenitors of the New Orleans scene – described the importance of infusing Mexican and Latin sounds into the genre.

“As Morton told the Library of Congress, ‘If you can’t manage to put tinges of Spanish in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning for jazz.’”

As New Orleans jazz became a starting point for a variety of other southern folk genres, the new life that Lewis had afforded it meant that it was borrowed by other artists across a variety of genres. Willie Nelson recorded it on his seminal “Red Headed Stranger” album. The Beach Boys released it under the title “Carnival” and the Atari video game company released it as the soundtrack to Pitfall II: Lost Caverns (albeit in a very bleepy style) on their Atari 2600 console.

The song also regained its Mexican roots somewhat, becoming a staple of early Tejano music. The genre would eventually morph into what we now know as Norteño, but few songs in the early days of the style better represented the fusion of north and south quite like “Across the Waves.”

It is a shame that Rosas has never truly gained the recognition he deserves for his work as a musical innovator. The genres that picked up his tune have all become iconic – but whatever the size of their modern audiences, they all owe their debt to an Otomí man who lived a short yet brilliant life more than a century ago.

By Mexico News Daily writer Chris Havler-Barrett