Every year, as summer draws to a close, Guadalajara celebrates its twin traditions of charrería and mariachis in grand style, with concerts, musicals, rodeos and fiestas all around the state: “more than 50 presentations filled with music and folklore.”

While todo el mundo knows what a mariachi is, not everyone has heard of charrería, a word that might be translated into English as ”everything related to cowboys,” but in modern times really refers to certain skills which cowboys or charros display in competition with one another.

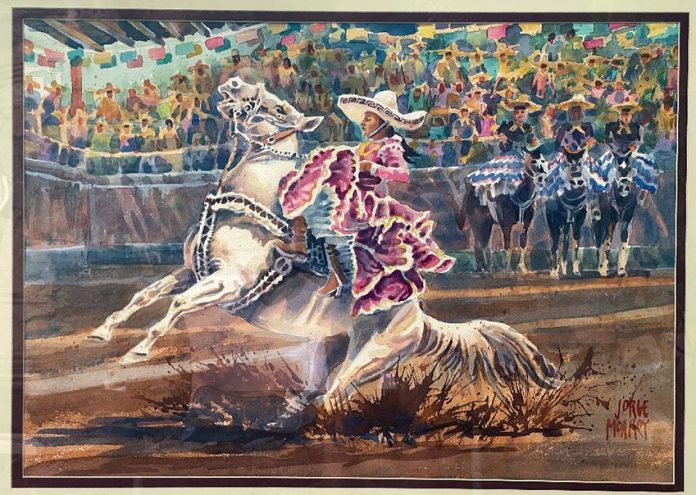

This year Jalisco kicked off its celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of mariachi music and charrería with an art exhibit inaugurated on Aug. 24 entitled Entre Lazos y Cuerdas (Among Lassos and Chords) featuring watercolor paintings, all related (of course) to charros and mariachis.

The expo — on display at the Guadalajara Chamber of Commerce until Sept. 30 — offers an excellent way for you to acquaint yourself with every aspect of these traditions.The art show features 59 paintings, all of them by members of the Jalisco Society of Watercolorists, and many of them for sale.

I asked one of those watercolorists, artist Jorge Monroy, what the public might be able to learn about charrería while visiting the art exhibit.

“When it comes to charros,” replied the artist, “my favorite themes are related to what they call las nueve suertes. These are nine skills that are tested in competition at lienzos charro, specially built arenas which regularly stage what those north of the border would call a rodeo.

Monroy then gave me a few examples of the suertes which take place at a lienzo charro – a competitive rodeo.

Pial

The Pial is a challenge requiring the charro to lasso a galloping mare while mounted on his horse. As soon as the mare runs through the loop of the lasso, the horseman must catch it by the hind legs (only). He then “dallies” or wraps the rope around his saddle horn in such a way that the friction will bring the racing mare to a complete stop in the shortest distance possible. In some cases the intense friction generated may literally produce a cloud of smoke.

Coleadero

Mounted on his horse, the charro must get close to a young bull and grab its tail, causing the bull to fall to the ground. The more times the bull rolls, the more successful the suerte. The entire trial takes place within a distance of 60 meters.

La Cala de Caballo

To execute this suerte, the charro must race his horse at top speed and then stop as quickly as possible. When the horse “puts on the brakes,” it slides forward and its hooves leave skid marks, known as rayas (lines), whose lengths are measured.

To the uninitiated, this may sound easy, but many consider this the most difficult suerte of all, and the ultimate demonstration of the oneness between rider and horse.

These and many other tests of horsemanship and roping feature in the watercolor expo.

The other theme of the art show is the mariachi, which has undergone an interesting evolution over the years.

The town of Cocula in Jalisco claims to be the birthplace of the mariachi. At first the music was referred to as son jalisciense, (the Jalisco sound) and the musicians played stringed instruments only, perhaps guitars and a harp. On top of that they weren’t dressed as charros, but wore the white shirt and pants of peasants.

And how about the word “mariachi?” What does it mean?

For years we were told that it’s a corruption of the French word mariage, because the musicians typically played at weddings in the days when France was trying to conquer Mexico.

Recent studies demonstrate that the term “mariachi” was well established long before the French invasion. A letter from a priest complaining to his archbishop about “the noise of the mariachis,” was written in 1848, thirteen years before the French invaded. The origin of the word continues to be debated.

If you have a chance to visit the exposition, you will have a perfect opportunity to examine the various techniques of Mexican watercolorists.

“Watercolor (acuarela in Spanish),” Jorge Monroy told me, “is considered by many to be the most difficult form of painting. Put a drop of water on cotton fiber paper and you can’t see if it is absorbed completely, so, if you put color on that surface, you don’t know what is going to happen. If it’s very wet, the paint will expand, if it’s a bit dry you’ll end up with a glob of color, a glob you don’t want to see. Watercolor always gives unexpected results.”

Oil or acrylic is different, he told me. “If you don’t like what you see, you can remove it with the spatula and put something else on top, but in acuarela, it’s impossible to make corrections. You have to get it right the first time around. You have to be sure of yourself and you have to succeed at the very first attempt. So the oil painter can relax in his studio, drinking a cup of wine and listening to music. He doesn’t have to fight the battle of the watercolorist, because he knows he can always correct a possible mistake. He has no worries.”

If you visit the show at the Chamber of Commerce (entry is free), you can learn about charros and mariachis as well as the intricacies of acuarela technique…and help a good cause, as a portion of art sales will be donated to families of policemen killed in the line of duty.

The Cámara de Comercio de Guadalajara is located at Av. Vallarta 4095 and is open Monday to Saturday, 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM until Sept. 30.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.