Throughout history, a few gifted souls have managed to turn momentous events into epic poems. We have the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Epic of Gilgamesh and now the Aztec Rhapsodies.

The theme of the rhapsodies is the fall of the Mexica empire as seen through Mexican eyes, and it’s a tale even more bizarre than the fall of Troy.

As the legend goes, a handful of unwashed Spaniards who didn’t know the local language walked into one of the best-organized cities in the world — a city protected by the most ferocious warriors in the Americas — and captured its leader without a hitch. That, indeed, is a story worth telling.

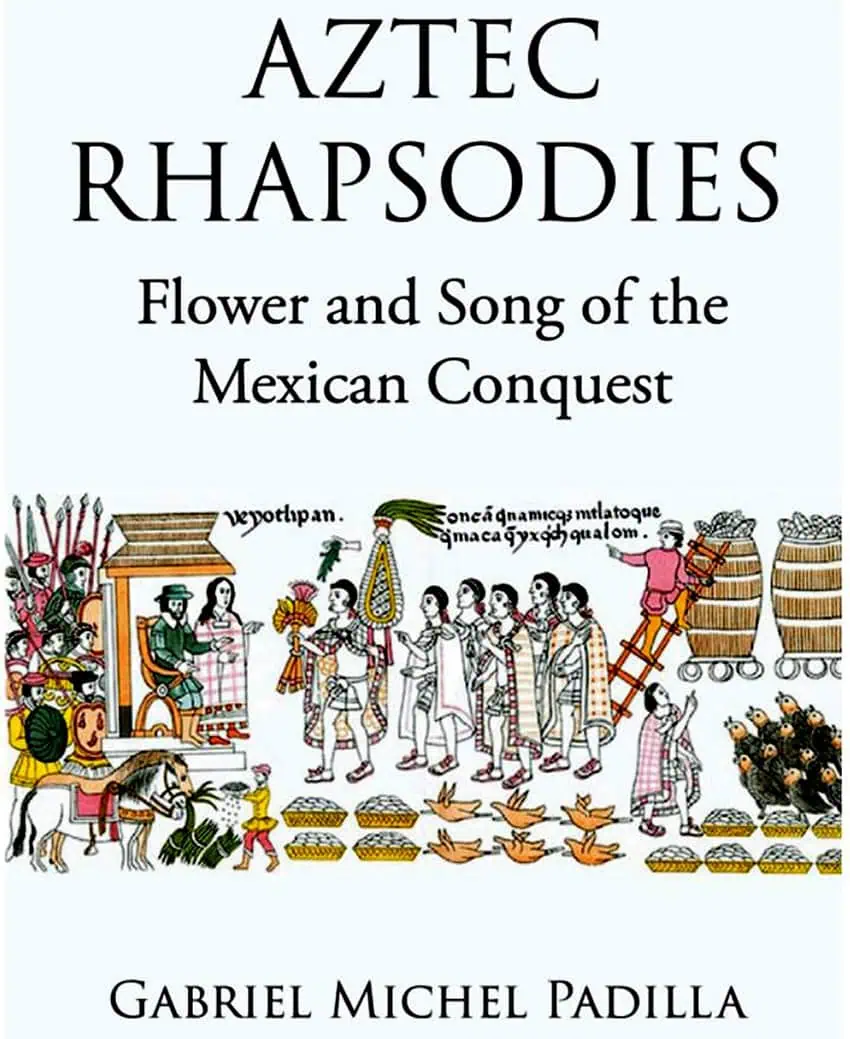

The tale is told in verse over 132 pages with more than 100 illustrations, taken mainly from 16th-century codices. “Aztec Rhapsodies, Flower and Song of the Mexican Conquest,” was published in 2024. It is now available on Amazon, both in print and Kindle form. And yes, it is in English!

The author of this most unusual work is Gabriel de la Asunción Michel Padilla, curator of a fascinating little museum in the town of El Limón, Jalisco, located halfway between Guadalajara and the Pacific coast.

Michel’s well-illustrated book of 48 rhapsodies begins with the landing of the Spaniards in Cuetlaxtlan (today’s Veracruz) in the year 1519. The book begins with these lines:

In the house of the flowers, of the music,

by the blossomy mansion of Mixcóatl,

where are hatched and sung anthems of battle,

here is woven in words, here is recited,

how ominously landed in Cuetláxtlan,

Castilian men proceeding from the east,

at the coastland governed by Pinotéuctli,

nearby the limits of the godly water,

the threshold of the sea, of twisted tides.

The following chapters relate Moctezuma’s reaction to the presence of those Castilian men, how he sent magicians and sorcerers to do them in — unsuccessfully — and how, fearing they were gods, he welcomed them to his palace.

We learn how the Spaniards allied themselves with the many tribes that hated the Aztecs, of the fierce battles that ensued, of the scourge of smallpox… and the day that the Spaniards grabbed Moctezuma by the arms and forced him to show them the storehouse of the national treasure.

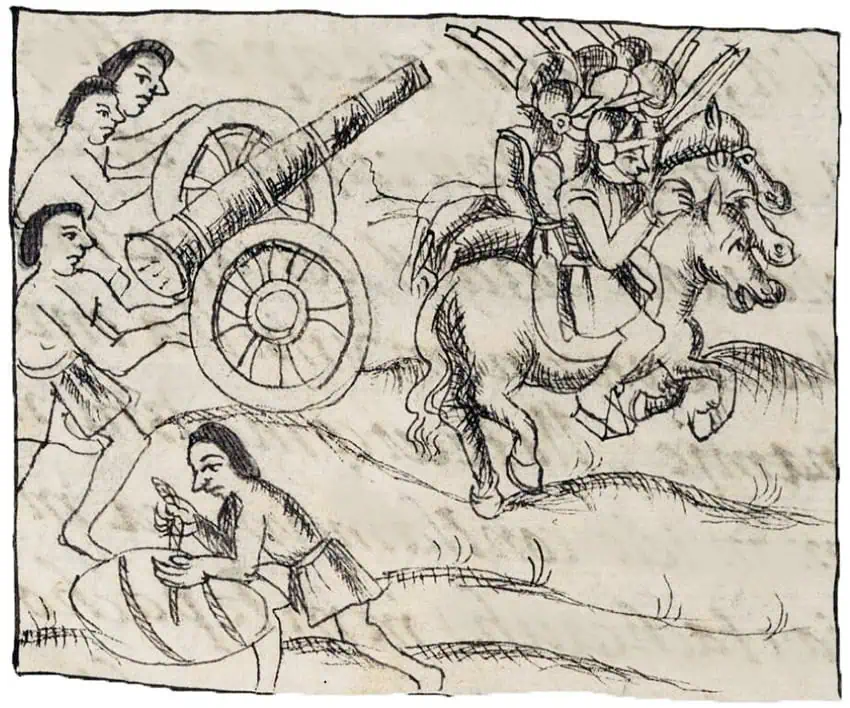

Of particular interest are the Aztec descriptions of guns and cannon and their impact upon Moctezuma:

Specially did it cause him to faint

when he heard how the guns discharged the shot,

how it resounded and thundered, terrifying.

There was fright, consternation, eardrums burst,

when the Spaniards ordained fire of the shot.

From within, a rock came forth, a round pebble,

It went along sparkling, it rained fire.

The smoke that came from it was fetid, foul.

When it went into the brain, the head was wounded.

When it struck a hill, it made a hole.

It was as if the mountain were demolished.

If the shot reached a tree, it turned into a sliver.

It was something amazing, awe-inspiring.

It was as if someone blew it away.

I asked author Gabriel Michel what inspired him to write an epic poem on the Spanish conquest.

“Many years ago,” he told me, “I was a seminarian, and in my studies of Greek, I came upon Virgil’s Aeneid, the epic poem which tells the story of the fall of Troy and the founding of the Roman Empire. At the age of 13, I told myself: “This is what I should be doing. I should apply this to my own country.”

At that point, Michel began his lifelong study of the Spanish conquest of Mexico, starting with Bernal Diaz de Castillo’s “True History of the Conquest of New Spain.”

“Later on,” said Michel, “I examined the writings of those who had been conquered, and I was truly astonished by what I found.”

Michel first wrote his own version of the Conquista in prose and then, bit by bit, rewrote it in verse, inspired, he says, by the writings of St. John of the Cross, whom he considered the very best poet of Spanish literature.

English speakers may glean the most from “Aztec Rhapsodies” by simultaneously reading chapters of the book “The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico” (2006) by historian Miguel León-Portilla. Both books tell the same story, but in a very different manner.

Like all epic poems, “Aztec Rhapsodies” is meant to be read aloud. Give it a try!

Should you ever travel through Jalisco, you may want to stop in El Limón to visit Gabriel Michel and his fascinating museum Museo Licho Santana, which offers a fine collection of everything from pre-Hispanic figurines to prehistoric fossils — such as an intact Ice Age gliptodont.

If you are interested in the Spanish version of “Aztec Rhapsodies,” you can get a copy here — or by contacting Gabriel Michel at Whatsapp 321 100 5138.

John Pint has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.