It all started with a wedding. In 1469, Isabella I of Castile married Ferdinand II of Aragon, uniting their two kingdoms and laying the foundation of modern Spain. The kingdom expanded further in 1492 when it forced the Muslims out of Granada. That same year, a self-educated visionary from Genoa came peddling his idea for finding a route to the wealth of Asia, not by rounding Africa, but by sailing westwards. Isabella I, seeing this as a way to circumvent the Portuguese monopoly on the eastern route, sponsored Christopher Columbus’s first Atlantic voyage.

Columbus indeed found land on the far side of the Atlantic, and he returned in 1493. This time, he established a settlement on the island of Hispaniola (modern Haiti and the Dominican Republic), creating a small foothold in a new world that still required exploration and mapping. It was, for example, uncertain if neighbouring Cuba was an island or, as Columbus believed, the most easterly point of mainland Asia. This would not be settled until 1508, when Sebastián de Ocampo finally circumnavigated the island.

The final voyage of Columbus

In 1502, Christopher Columbus’ fourth and final voyage brought him to the American mainland, and he sailed as far north as modern Belize. On July 30, 1502, his party spotted a large canoe approaching from the west. The canoe was carved from one large tree trunk and was powered by 25 nude rowers. As far as we can tell from the limited accounts, this was a Maya trading canoe from the Yucatán, carrying a cargo of trading goods that included ceramics, cotton, copper, and stone axes, war clubs and cacao. It was not a friendly first interaction. The Europeans looted whatever took their interest from the cargo and seized the elderly Maya captain to serve as their guide.

It had been a difficult trip, noted for unhelpful winds and currents, shallow reefs and sudden storms, and it ended with the crew being marooned on Jamaica for several months. Columbus had not rounded the eastern point of the Yucatán. Had he done so, he would have been the first European to see the great Maya cities. He had, however, seen enough to convince himself that they had been sailing along the shores of a continent, and one that was home to people far more technically advanced than the small villages encountered on the Caribbean islands. Columbus was more certain than ever that he had reached the eastern shores of Asia.

Spanish advances in the Americas

In 1510, the Spaniards made their first attempt to establish a settlement on the South American mainland, founding the colony of Santa María la Antigua del Darién in Colombia. The following year, a ship sailing out of this colony hit a sandbar off the coast of Jamaica. Most of the crew and passengers took to a small boat, but unable to combat the current and wind, they were swept westwards to the Yucatán and captured by the Maya. Somehow, two of them, a friar called Jerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, who was probably a sailor, escaped into the jungle.

In 1511, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar arrived in Cuba with instructions to bring the island more firmly under Spanish rule. The island proved far more welcoming to the Spanish than Hispaniola had been. The Indigenous Taínos, Ciboneys and the Guanajatabeyes, having generally been left alone by neighbouring islanders, had neither weapons nor a warlike culture. The forests and beaches provided sources of food, such as cassava, large lizards, turtles and wild birds, that offered a more varied and therefore healthier diet. Although the rumours of gold were greatly exaggerated, the Spanish brought in settlers to populate the small towns that Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar established around the island.

The Spanish settlement of Havana

One of these new settlements was Havana. Built around a natural bay, it lay to the north of the island at the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico. This gave easy access to the Gulf Stream, the main ocean current that navigators followed when returning to Europe, so it rapidly developed as an important port. By 1515, Cuba was largely pacified and already becoming the heart of Spanish interest in the Americas.

The first years of Spanish exploration and settlement had not produced any significant quantities of gold. Neither had ships been able to discover a trade route to Asia. Instead, it was plantations, particularly the growing of sugar and tobacco, that were proving the most profitable business. However, plantations were dependent on enslaved labor, and the Spaniards had brought new diseases with them, which had decimated the local Indigenous populations. Exploring the still uncharted lands to the west was increasingly motivated by the search for more people to enslave, and while ships leaving from Hispaniola had tended to head towards South America, the ever more important harbour of Havana was far closer to the Yucatán. The Spanish were about to turn their attention to Mexico.

The first Spanish voyages to Mexico

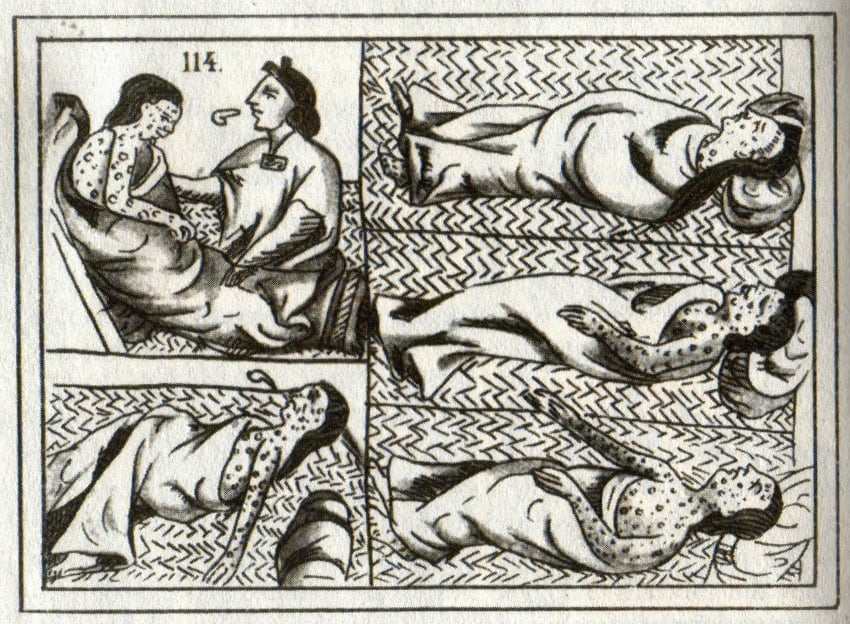

Around 1515, or perhaps the following year, the Maya were hit by a great plague. The sickness caused large, rotting pustules and is thought likely to have been smallpox. Whether it was carried by those handful of shipwrecked prisoners or brought overland by Indigenous peoples trading with the Spanish settlement in Panama is uncertain. Whatever the source, this was the Maya’s first experience of the European diseases that would take such a terrible toll in the years ahead.

In February 1517, 25 years after Columbus first sailed to the Americas, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba set out from Cuba with a small fleet of three ships. Little is known of Córdoba’s life before this. He had been born in Spain, had acquired land and wealth in Cuba, and was sailing in search of gold and people to enslave. These waters were stormy and dangerous, but at least the Spaniards now had some knowledge of what to expect. Antón de Alaminos, who had served as pilot under Christopher Columbus, was sailing with Córdoba, and three weeks after leaving Cuba, having survived a two-day storm, they sighted the northeastern tip of the Yucatán Peninsula. Here they saw a Maya city upon a low hill, which they called Gran Cairo, due to its size and its pyramids. As far as can be ascertained, they had reached Isla Mujeres.

Córdoba’s explorations of the Yucatán Peninsula

The initial reaction of the Maya was aggressive, and a Spanish party that went ashore at Chakán Putum was ambushed by a large group of warriors. Several Spaniards were killed, and others were wounded during the attack. However, the Spanish were able to continue into the city, reaching a small plaza, where they looted the temples.

They also captured two Mayas to be used as guides. One man injured in the attack was the future historian Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who returned to the ship with three wounds. One of these, an arrow that had pierced his ribs, was quite serious, but he survived. Bernal Díaz del Castillo’s story is typical of a Spanish adventurer of this age. Born in Spain to a modestly wealthy family, he had schooling and a talent for languages but few prospects. As a young man, he had sailed for the new colonies, but here, too, there seemed to be limited opportunities for the later arrivals. He turned to soldiering, sailing first with Córdoba and later with Hernán Cortés. Many years later, he would write an account of these events in “Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España.”

Over the next fifteen days, Córdoba’s fleet slowly followed the coastline west and then south, but they were running into problems. The poor quality Cuban water casks were leaking, and the need to find fresh water became critical. Another problem was that the Maya stone arrows tended to shatter on impact, and some of the wounds that had seemed minor were now becoming infected. Córdoba headed north for Florida, where they were again attacked, at which point the expedition was abandoned and they headed back for Cuba.

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar’s fleet arrives in the Yucatán

The following year, spurred in part by the gold Córdoba had looted from the temple at Chakán Putum, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar assembled a fleet of four ships and placed it under the command of Juan de Grijalva. They departed Cuba in April with Antón de Alaminos, now a veteran of these waters, once again the pilot. They also carried the two Indigenous peoples captured at Chakán Putum. These men had been given Spanish names, being known as Julianillo and Melchorejo, and presumably had learnt a fair bit of Spanish. They would act as both guides and interpreters.

The fleet rounded Cuba and reached the east coast of the Yucatán, where they became the first Europeans to see Cozumel. Turning north and following the coastline, they reached Chakán Putum. where they were again attacked. A few crew members were killed, and many, including the captain, were injured. They were attacked again at San Juan de Ulúa, this time by Indigenous people in canoes. Maya aggression prevented de Grijalva from establishing a small garrison and claiming these lands for Spain.

In other places, they were able to trade, acquiring some jewellery and “low-grade” gold items. One ship returned to Cuba to seek reinforcements, and the rest pushed on. They reached Tabasco, where they named the local river the Río Grijalva after their captain. It was around this time that they became the first Spaniards to encounter the Mexica, coming across a man called Pinotl, a representative of the great Moctezuma II. The Spaniards heard of a great inland city, while Pintol returned to Tenochtitlán with news of these strange foreigners, men with beards who sailed the seas in their great white ships.

Cortés comes to Mexico

On their return, the rumors of gold once again spurred excitement, and Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar selected Hernán Cortés to lead the next expedition. A decade of soldiering in the New World had seen Cortés grow rich in land and government positions, and he gathered a force of 11 ships, 500 men, as well as 13 horses. Backed by such an army, Cortés could be far more aggressive with the local Yucatán chieftains.

While on Cozumel, a canoe arrived with three men, one of whom rushed up to the sailors and asked in Spanish who they were and who their king was. This was Jerónimo de Aguilar, one of the last two survivors from the lifeboat the tides had swept here in 1510. Gonzalo Guerrero had also survived but had assimilated into Maya life and now had tattoos, piercings, a wife and several children. He would stay in the service of his Maya lord. Jerónimo de Aguilar, however, being a religious man, had rejected such temptations and sailed with Cortés as he departed for the north and his conquest of the great Mexica empire.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life-term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.