Slavery is as old as civilization and has taken a wide variety of forms across history, but if you speak of slavery today, most people will envision the Atlantic slave trade, which snatched Africans from their homeland and transported them far away to be sold as property.

This is why Andrés Reséndez, Mexican historian and professor at UC Davis, wrote “The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America,” published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2016.

The book’s very title suggests that Reséndez addresses a system perhaps as bad as the one perpetrated upon Africans, and it also suggests that not many people know about that system.

I must confess I was jolted by what the author has to say about Christopher Columbus and his plans for the lands he discovered. I was obliged to quickly remove Columbus from that pedestal he had occupied in my mind since childhood.

Apart from being a skillful and imaginative navigator, Admiral Christopher Columbus, reports Reséndez, was also a shrewd and experienced businessman. When he secured a sponsorship for his voyage from Ferdinand II and Isabella I in April of 1492, he insisted that clauses be added to the contract that gave him one-tenth of “all the merchandise, whether pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices and any other marketable goods of any kind, name, or manner that can be bought or bartered.”

Upon encountering problems in extracting tribute from the Indians of Hispaniola, where he had established a base, Columbus noted the “tameness” and “ingenuity” of the local people. In the very first letter he wrote upon his return to Spain, addressed to Royal Comptroller Luis de Santangel, he promised to deliver “as many slaves as their Majesties order to make, from among those who are idolaters.”

He wrote another revealing letter to Ferdinand and Isabella early in his second voyage to the Americas, in reference to dozens of captive Indigenous people he had just sent to Spain, apparently as samples of “marketable goods.”

“May your Highnesses judge whether they ought to be captured,” says the admiral, “for I believe we could take many of the males every year and an infinite number of the women.”

Columbus was not bashful about touting the quality of the “human merchandise” he promoted:

“May you also believe that one of them would be worth more than three black slaves from Guinea in strength and ingenuity, as you will gather from those I am shipping out now.”

A year later in 1495, he sent 550 Indigenous captives to Spain to be auctioned off as slaves. He crammed them into four caravels, light sailing ships only meant to hold 100 individuals each. Two hundred of them perished during the journey.

With this voyage, Reséndez says, Columbus inaugurated the infamous Middle Passage that would later kill countless Africans packed like spoons into filthy holds for a typical voyage of four to eight weeks.

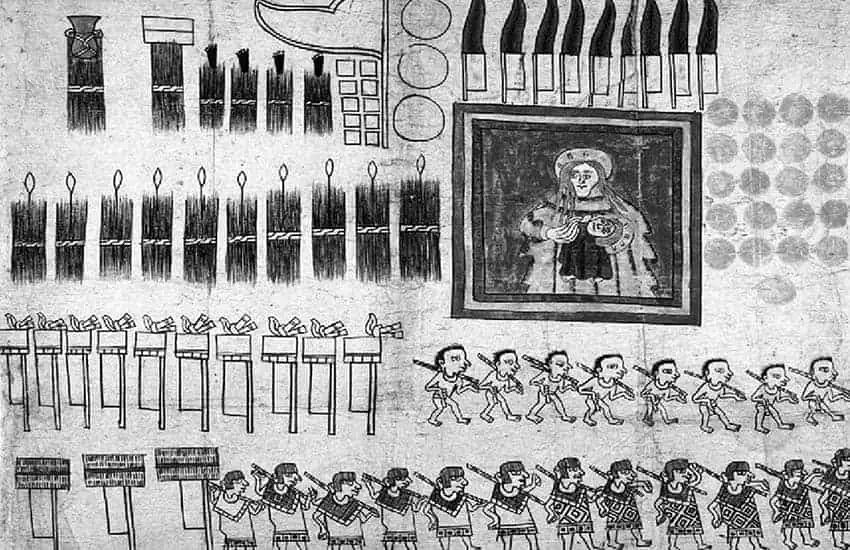

Once they had established a foothold in Mexico, conquistadors were rewarded for their participation in the conquest not just with booty but with parcels of land known as encomienda. The Indigenous people already living on that land were assigned to the new owner — now an encomendero — as his workers.

Though the nominal arrangement was that the encomendero would see to the Christian education and safety of his workers in exchange for labor and tribute, the reality was that they were enslaved.

In addition to their agricultural labor, Indigenous slaves were an essential and integral part of the mining industry, which was soon flourishing all over Mexico: a mine was always with the slaves forced to work it.

The leader in mining was Hernán Cortés himself. Notarial records show Cortés spending more than 20,000 pesos in a single day to buy three mines and hundreds of slaves.

“Ultimately,” says Reséndez, “not only was Cortés the richest man in Mexico, he was also the largest owner of Indian slaves. And wherever Cortés led, others followed.”

Most mines required digging, usually downward through solid rock. Since explosives were not introduced until the early 18th century, miners had to dig with simple picks and crowbars and wedges, working from sunrise to sunset. On top of this they faced the dangers of tunnel collapses and, in the long run, death from silicosis, which filled their lungs with scar tissue.

And then there was the job of carrying the ore to the surface, up notched pine logs called “chicken ladders,” in leather bags weighing around 150 kilos.

Perhaps the most horrible job of all in mining work was the “patio process.” Silver ore was crushed to powder, spread over a patio and sprinkled with mercury. Water was added to form sludge. Then a slave, still wearing shackles, had to walk over this toxic mud in order to mix it thoroughly.

“This job,” says Reséndez, “invariably resulted in serious health problems, as the poisonous metal would enter the body through the pores and seep into the cartilage in the joints.”

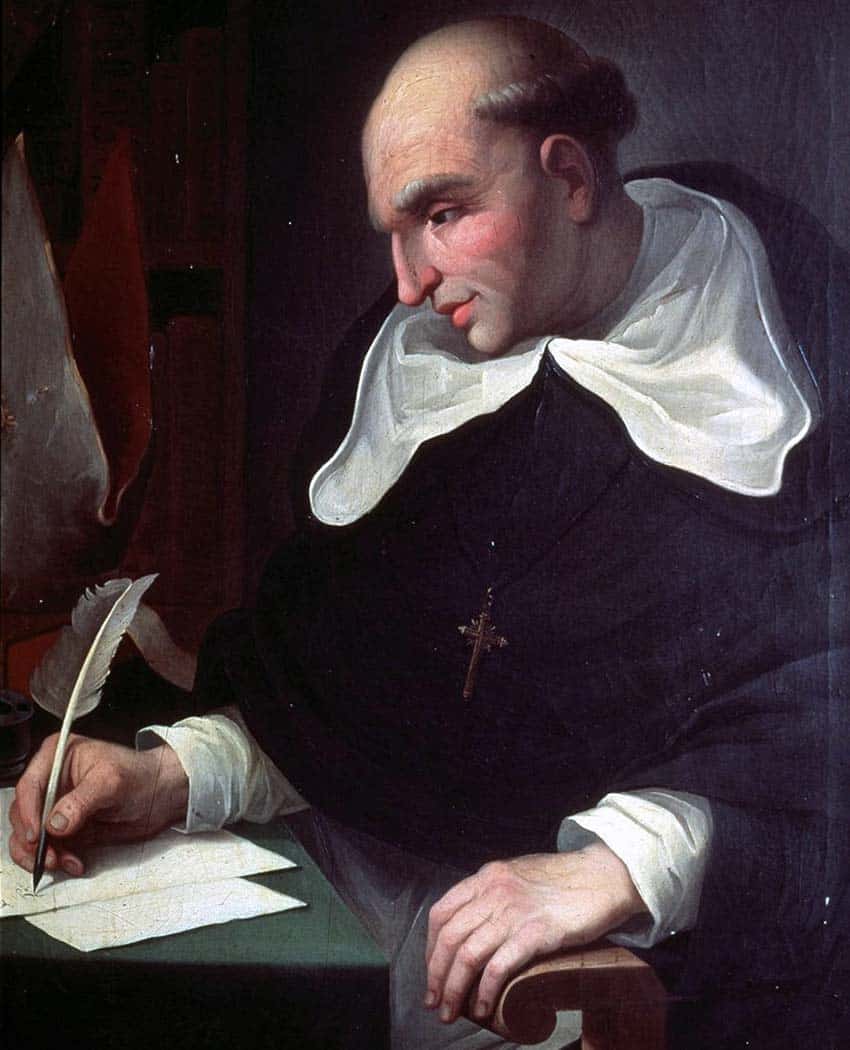

Fortunately, in the Spanish court there was a group of activists trying to mitigate the worst excesses of the conquistadors. Prominent among them was Bartolomé de Las Casas, a Dominican friar who witnessed Spanish atrocities in the Caribbean firsthand.

One of the friar’s favorite tactics to win people over to his cause, says Reséndez, was to scandalize court members by reading aloud from a manuscript that would later become his book “A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies,” which described the manner in which the Spaniards “dismember, slay, perturb, afflict, torment and destroy the Indians by all manner of cruelty: new and [diverse] and most singular manners such as never before seen or read of.”

University students today around the world still learn about the gory details of the Spanish colonization of the Caribbean from this book.

Eventually, new legislation known as the New Laws aimed at establishing a different relationship between Spain and its Native American vassals. The new code stated that Indigenous people were free vassals of the crown.

“So from now on,” it declared, “no Indian can be made into a slave under any circumstance.”

Spaniards in the New World who had long relied upon Indigenous slave labor were in shock. Naturally, they tried to use every trick in the book to continue as before, but now they had to worry about getting caught by the crown.

As in his retelling of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s odyssey across America, Andrés Reséndez’ prose is captivating. Once you start reading “The Other Slavery,” you may find it hard to put down.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.