A treasure-trove of knowledge on 16th-century Indigenous Mexican culture is now available to the global public, via a new digitization of the Florentine Codex in Nahuatl, Spanish and English.

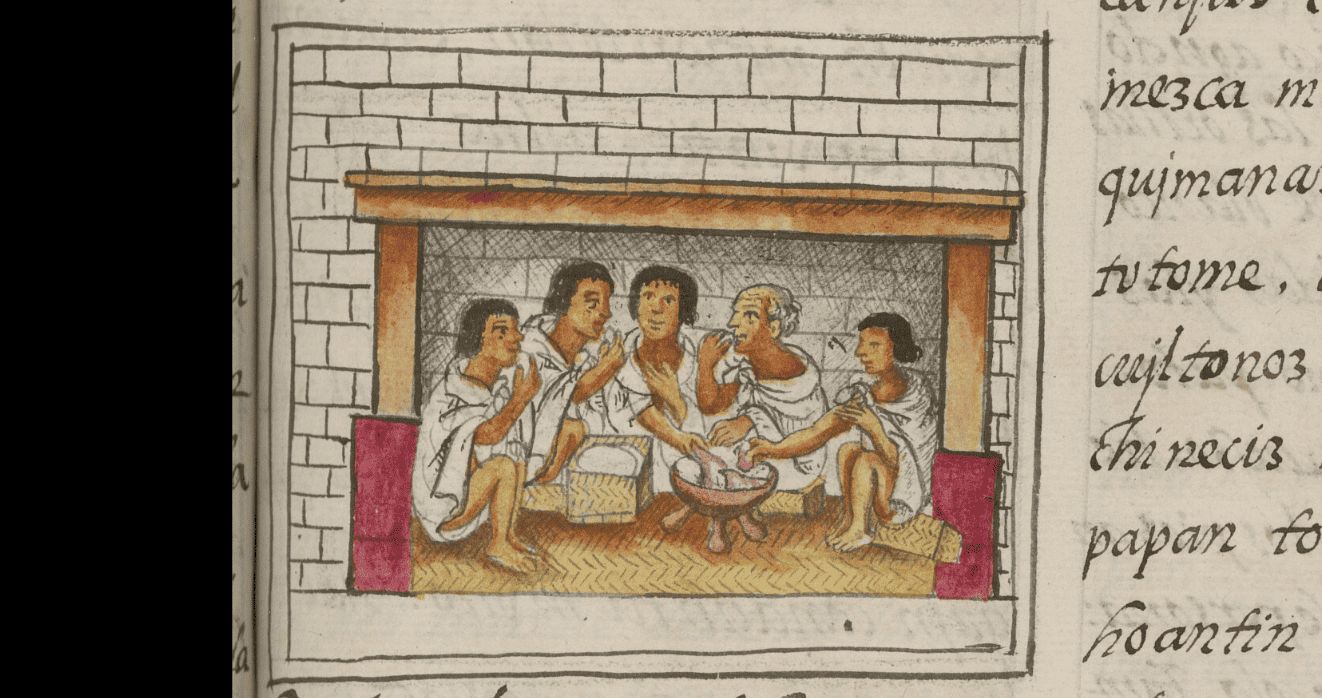

The Codex is a 12-book encyclopedia of Mexica (Aztec) life, written between 1575 and 1577 by Nahua scholars, based on interviews with elders who lived before and during the Spanish conquest. (Nahua refers to the Nahuatl-speaking Indigenous people of Mexico and Central America, a group that includes the Mexica.)

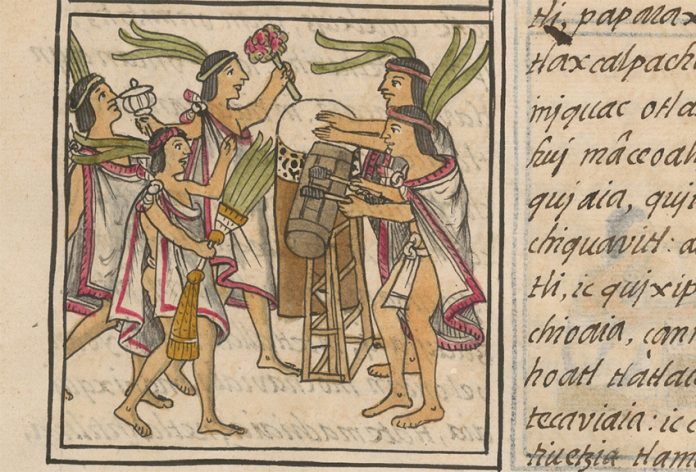

It also contains nearly 2,500 images by Nahua artists, depicting the daily life and mythology of their people. It was co-created and translated into Spanish by the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, who hoped that knowledge of Nahua culture would help convert them to Christianity.

Although the Codex was first digitized a decade ago, a project led by UCLA’s Latin American Institute and the Getty Research Institute has produced a new, easily navigable and searchable version, with the languages modernized and a parallel English translation.

The project is the result of seven years of work by 68 researchers, led by Mesoamerican art expert Kim N. Richter. The collaborators included Indigenous scholars who deciphered not only the ancient Nahua text, but also the various logograms — pictures used to represent words — embedded in its artwork.

“[The Codex] is the most remarkable cultural and intellectual product of the early Americas,” said Kevin Terraciano, chair of the UCLA history department and co-founder of the project. “The fact that many Nahua people in Mexico, including Nahua scholars who are working with us on the initiative, did not even know about the Florentine Codex before we began collaborating, suggests the real value of the project.”

One of the many fascinating aspects of the Codex is that the Spanish and Nahuatl texts are not direct translations of each other, but separate texts that present different views. The new translations will therefore allow non-Náhuatl-speaking people to read for the first time its Indigenous authors’ perspective on the colonization period.

Eduardo de la Cruz Cruz, a collaborator of the project and director of the Institute of Teaching and Ethnological Research of Zacatecas, described in a Getty symposium the impact of presenting the Codex to primary and secondary school children in Nahuatl-speaking communities in La Huasteca, a region along Mexico’s Gulf coast.

He said the children had been brought up with access only to European sources that described their ancestors as ignorant, violent and evil. Reading the Codex allowed the children to hear their ancestors’ own voices for the first time and find new pride in their history and culture.

“Believing that your heritage is inferior and that civilization came from outside must make you feel very small as a young Indigenous person, especially when you have experienced discrimination,” Richter said. “We are eager to see how scholars will utilize this resource to better understand the agency of the individual authors and artists who worked on the Codex — Sahagún and his many Nahua collaborators.”

With reports from UCLA, The Los Angeles Times and La Jornada Maya