In 2023, two important things happened in a beautiful and little-known corner of northern Mexico – the 100th anniversary of Pancho Villa’s death and the naming of Parral, Chihuahua as a Pueblo Mágico.

With luck, the two will eventually lead to more interest in Villa’s “home range,” the rural lands between the cities of Durango and Chihuahua. The journey offers both stretches of unspoiled natural beauty, and a testament to some of Mexico’s most colorful and chaotic history.

No other region in Mexico identifies more strongly with Villa than here. José Doroteo Arango Arámbula was his real name but the world knows him better as Francisco, or Pancho Villa. He was a complicated figure in a complicated time – part of a decade-long struggle for power among various factions that would define modern Mexico.

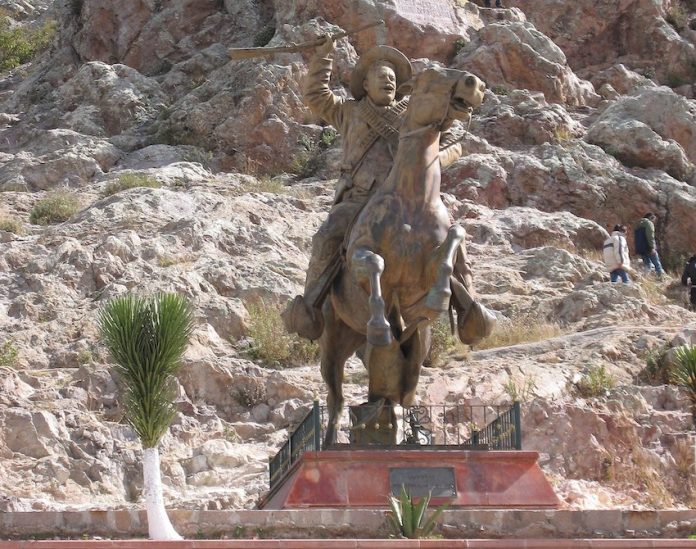

At his height, Villa and his División del Norte army would swiftly push south as far as Mexico City, but would also then be swiftly pushed back to Durango. Here Villa could not be beaten – a lifetime of being on the run from the law and his enemies meant he not only knew the area like the back of his hand, but that the locals supported him, too.

Until, of course, he was assassinated in Parral, Chihuahua.

To start exploring this region, the logical place to start is the city of Durango. Major highways take you there from Mazatlán and even Mexico City, (there is also an international airport), and it has much to offer visitors including Baroque architecture, a sprawling market, colonial history and, of course, mezcal. The city honors Villa, the state’s native son, with a 10-hall museum opened in 2013 in the downtown Zambrano Palace, which gives a good introduction to his life and times before you begin trekking north.

Only a couple hours away from Durango is San Juan del Río, Villa’s birthplace. Even before you arrive, you will notice how much unspoiled nature there is just driving on Highway 45. Despite its claim to the Villa name, San Juan itself is still a typical rural mining and agricultural municipality, instead of a tourist attraction, although the town has several points-of-interest, including its 16th/17th century church and La Coyotada, the house where Villa was born.

Heading further north, the next stop is just before the Durango/Chihuahua state line, at the very rural municipality of Ocampo. The main attraction here is the former Canutillo Hacienda. Abandoned during the Revolution, the 87,000 hectare estate enticed Villa to sign the Sabinas Accords with then-President Adolfo de la Huerta to lay down his arms and become a civilian.

Back among the mountains and forests that served to protect him so well for decades, Villa and his allies spent three years growing crops and providing locals with work and education.

After Villa’s death in 1923, the hacienda was abandoned again, its contents ransacked and its lands eventually redistributed. In 1978, the federal government converted the main house into a regional museum. The building proper is in good condition and the guide very knowledgeable about Villa, but Canutillo needs much work before it really can be called a “regional museum.” Villa is important, but there is so much more to northern Durango.

So far, the state has done little to promote tourism here, prompting organizations such as Sombreros Unidos de Ocampo to take on the monumental task of developing infrastructure to let people know about the area’s impressive natural beauty, indigenous and colonial history, and more. If you visit, please contact the Sombreros beforehand as they are your best bet for lodging and guides.

Villa’s banking needs took him regularly to Parral, which would eventually seal his doom. On July 20, 1923, his car was ambushed by gunmen, killing him and the other occupants instantly. Perhaps Villa was a little too optimistic that someone of his caliber could just “retire.”

Parral is in the valley north of the El Toche mountains, which separate Durango and Chihuahua. Here, the land is noticeably drier, and the architecture is much more norteño, more like the Mexico of Hollywood films.

Although the town has an important history of mining and Indigenous multiculturalism, its Pueblo Mágico status is directly related to Villa. He was not only murdered here, but local Elisa Griersen faced down the U.S. Army here, when they passed through looking to capture Villa. They never did.

To get a taste of just how important Villa is to the town’s identity, visit during the Jornadas Villistas (Villa Days) in July, which feature a horseback parade with participants in period attire and a reenactment of Villa’s death.

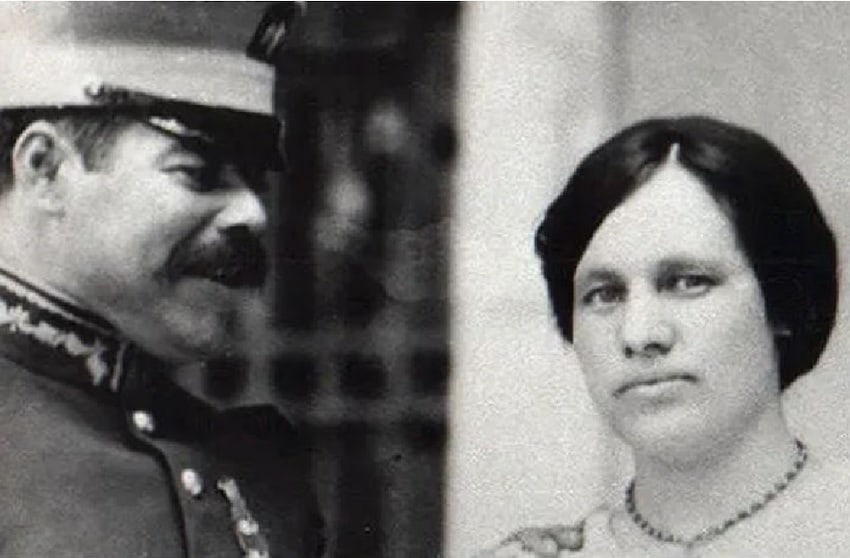

This is not Chihuahua’s only association with Villa. During the height of his power, the general served as the state’s governor for short periods in 1913 and 1914. He bought a mansion here, renaming it Quinta Luz in honor of his wife, Luz Corral de Villa.

She would remain in this house the rest of her life, playing a pivotal role in preserving Villa’s legacy. Here, she established a museum to him and his army, preserving many of his belongings.

Just before her death in 1982, she negotiated a deal with the Defense Ministry to take over the building and completely remodel it. Today it is the Historic Museum of the Revolution, managed by the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). The museum’s collection is extensive and even includes the car Villa was assassinated in.

Villa and his home range are particularly important now that history is reassessing his role in the “pantheon” of figures of the Mexican Revolution. For decades, he was vilified as a violent bandit by both the U.S. and Mexico, in part because he attacked the border looking to draw Mexico’s northern neighbor more directly into the internal conflict.

Over the course of the last century, both Mexico and the U.S. have produced books and films about Villa, slowly mythologizing his role in history, and in the 1970s, the general’s remains were moved to a place of honor at the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City. The 100th anniversary has offered new opportunities with President López Obrador paying homage in Villa’s birthplace and Star Plus putting out a series about his life and times.

It may be about time that a man seen as little more than a bandit in the U.S. – and his homeland – got their due.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.