Every March 21, Mexico celebrates the birth of Benito Juárez, the Zapotec boy who became a president, hero and symbol of just about everything Mexican. Schoolchildren memorize his words, politicians invoke his name, and his stern face stares down from statues across the nation. If you have a peso, you probably have Benito Juárez in your pocket right now.

Juárez was born in 1806 in the small village of San Pablo Guelatao, Oaxaca, a place so quiet you could hear a tortilla flip from a mile away. He spoke only Zapotec until the age of 12. Orphaned at three, he was, by all accounts, a quiet, serious boy.

But he learned Spanish. He studied law. And then, somehow, he overcame his humble beginnings and changed the fate of a nation. He became president not once, not twice, but five times. He fought off European invaders. He pushed for reforms that would put power in the hands of the people. And he did it all with the charisma of an overworked accountant.

A turbulent start in politics

Juárez had a roller coaster journey to becoming the unwavering leader of Mexico. He got involved in Liberal Party politics early in life and was elected governor of his home state in 1848, a role in which he made an enemy of Antonio López de Santa Anna. When Santa Anna came back to power for the last time in 1853, Juárez was imprisoned and exiled for his liberal views. It was not the first time he would be on the run in the coming years.

Juárez fled to New Orleans, where he spent two years in obscurity, working as a cigar maker and plotting the future of Mexico with other exiled liberals, waiting for the right moment to return home. That moment came in 1855, when Santa Anna was overthrown in the Ayutla Revolution and Juárez returned as Minister of Justice in the new liberal government that would shape Mexico’s future.

La Reforma and the Constitution of 1857

Juárez was, at his core, a reformer. He believed in laws, institutions, and, above all, the idea that a country should belong to its people, not to the Church or a handful of elites. He pushed for La Reforma, a series of laws that separated church and state, confiscated Church and communally-owned Indigenous lands and attempted to turn Mexico into what the liberals saw as a modern republic, kicking and screaming if need be. Juárez’s faction of the Liberal Party wrote the Constitution of 1857, incorporating these provisions as the iron-bound law of the land.

Naturally, this made a lot of powerful people very angry. The Catholic Church, which had been running things for quite some time, suddenly found itself on the losing end of history. Conservative elites, who preferred their peasants obedient and illiterate, saw Juárez as a dangerous man. And when Mexico’s ruling class gets uncomfortable, history tells us they usually do something drastic.

The Reform War and the Second French Intervention

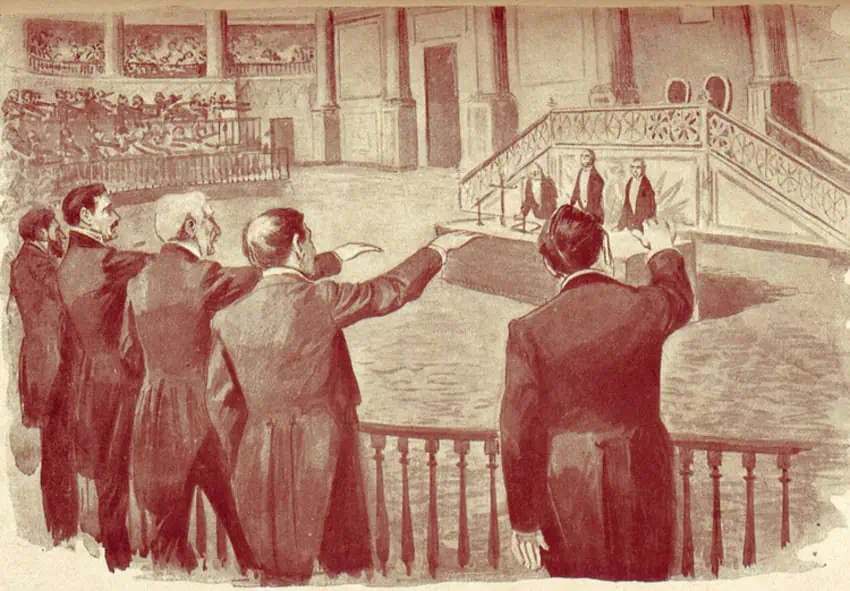

In December 1857, the conservatives rebelled against the new constitution, convinced liberal President Ignacio Comonfort to overthrow his own government and plunged Mexico into civil war. As Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the presidency legally passed to Juárez, who led the liberal government to military victory over the conservatives in 1860 and handily won the presidential elections of 1861. But the conservatives weren’t defeated yet, and they still had a trick up their sleeve.

Enter Maximilian von Habsburg, a well-dressed Austrian sent by Napoleon III to rule Mexico. With the support of the Mexican conservatives, France installed Maximilian as emperor, and suddenly Juárez found himself again leading a government on the run, chased across Mexico by a man who had absolutely no business being there.

Did Juárez surrender? No. Did he strike a deal, as Maximilian offered him? Absolutely not. Instead, he waged a guerrilla war against the conservatives and the French. And when the tides turned, and Maximilian was finally captured, Juárez had him tried and executed. No exile, no second chances. Just a firing squad and a clear message: Mexico would not be a European colony anymore.

Juárez had won. He had fought for democracy, for the people, for a government free from corruption and foreign influence. But then came the tricky part: governing in a time of peace.

The Restored Republic

Like many great revolutionaries before him, Juárez found that running a country is a lot harder than fighting for one. His reforms, such as the Lerdo Law, were meant to break up communal Indigenous lands to create private property and stimulate the economy — in reality, wealthy landowners and speculators bought up most of the newly private land.

While noble in principle, these reforms often did more to alienate people than unite them. The rural poor, many of whom had joined Juárez’s forces during the war, didn’t necessarily see their lives improve under his leadership. The Church, wounded but still powerful, continued to resist him. His enemies in government accused him of clinging to power, of ignoring dissent, of being just as dictatorial as the men he had fought against.

Still, Juárez kept getting reelected, often against strong opposition from other liberals. He centralized power in ways that made even his allies nervous. Some of his closest supporters defected and even revolted against his government in 1871, including, ironically enough, Porfirio Díaz, the general who would later rule Mexico as a dictator for over 30 years. The revolutionaries had become the establishment. And like so many before him, Juárez began to look less like a radical reformer and more like a man who simply couldn’t let go.

Benito Juárez is still kicking

In 1872, Juárez died of a heart attack at his desk. His legacy, however, refused to rest. Today, Benito Juárez is remembered as Mexico’s Abraham Lincoln, a man of the people who believed in justice and equality. His face is on the money. His birthday is a national holiday.

And yet Mexico still argues about him. They argue about his reforms, his decisions, his stubbornness. Some call him a hero. Others, a tyrant. Maybe that’s because his struggles still feel so present in Mexico. In some ways, the battles he fought — between rich and poor, liberal and conservative, progress and tradition — have never really ended.

Stephen Randall has lived in Mexico since 2018 by way of Kentucky, and before that, Germany. He’s an enthusiastic amateur chef who takes inspiration from many different cuisines, with favorites including Mexican and Mediterranean.