Mexico — home to the world’s second-largest Catholic population after Brazil — boasts unique traditions to mark the end of Lent during Holy Week. Influenced by a blend of pre-Hispanic customs and Hispanic culture — in addition to cultural modern elements like Coca Cola – these rituals vary widely by region.

Here are four of the most authentic Holy Week rituals and processions around Mexico to catch during Holy Week.

Dance of the Judases in Pajacuarán, Michoacán

In a colorful and lively display of faith, Pajacuarán, a small town in northeastern Michoacán, celebrates Holy Week with a procession known as the Dance of the Judases.

Combining Indigenous and Christian elements, the parade’s origins date back to the 19th century, when the priest Secundino Bautista evangelized the region’s Indigenous inhabitants by fusing their agricultural dances with Christian mysticism.

During the parade, which occurs on Holy Wednesday, dancers wear elaborate masks and tunics decorated with embroidery. They also carry sandals and a chirrión, a whip, they crack during their walks.

Roosters and Coca-Cola for Jesus in Chiapas

San Juan Chamula, a municipality located in the Chiapas highlands, is home to a distinctive and perhaps surprising practice that combines roosters, Coca-Cola and Indigenous beliefs.

In preparation for Holy Week, villagers walk into the forest to cut down a cypress tree after offering a prayer asking for permission and forgiveness from the tree. The giant log is then brought to the main church.

Then, on Holy Thursday, a rag doll representing Judas Iscariot is “punished” by being imprisoned and hanged for betraying Jesus.

But one of the most distinctive rituals happens inside the dim, incense-filled San Sebastián church, where roosters are sacrificed as offerings in an act believed to cleanse the faithful of evil and illness.

Bottles of Coca-Cola are placed at the altar and offered to the saints. Villagers believe the cola’s fizziness expels bad spirits and purifies the soul.

The presence of Coca-Cola in the ritual reflects cultural syncretism, as the soft drink has become deeply engraved into locals’ daily lives and religious practices.

How the Chihuahua Rarámuri defend God

Known in the Indigenous Rarámuri language as Comonorirawachi (“when we walk in circles”), this Holy Week celebration in the Sierra Tarahumara mountain range is a deeply spiritual event that combines ancestral beliefs with Christian elements.

Symbolizing the eternal struggle between good (God) and evil (the devil), the celebration centers around solemn processions encircling temples, symbolizing a “cordon of belief” in God’s defense.

Throughout the week, staged battles take place between the “Pharisees,” who represent the forces of evil, and the “soldiers,” the defenders of God.

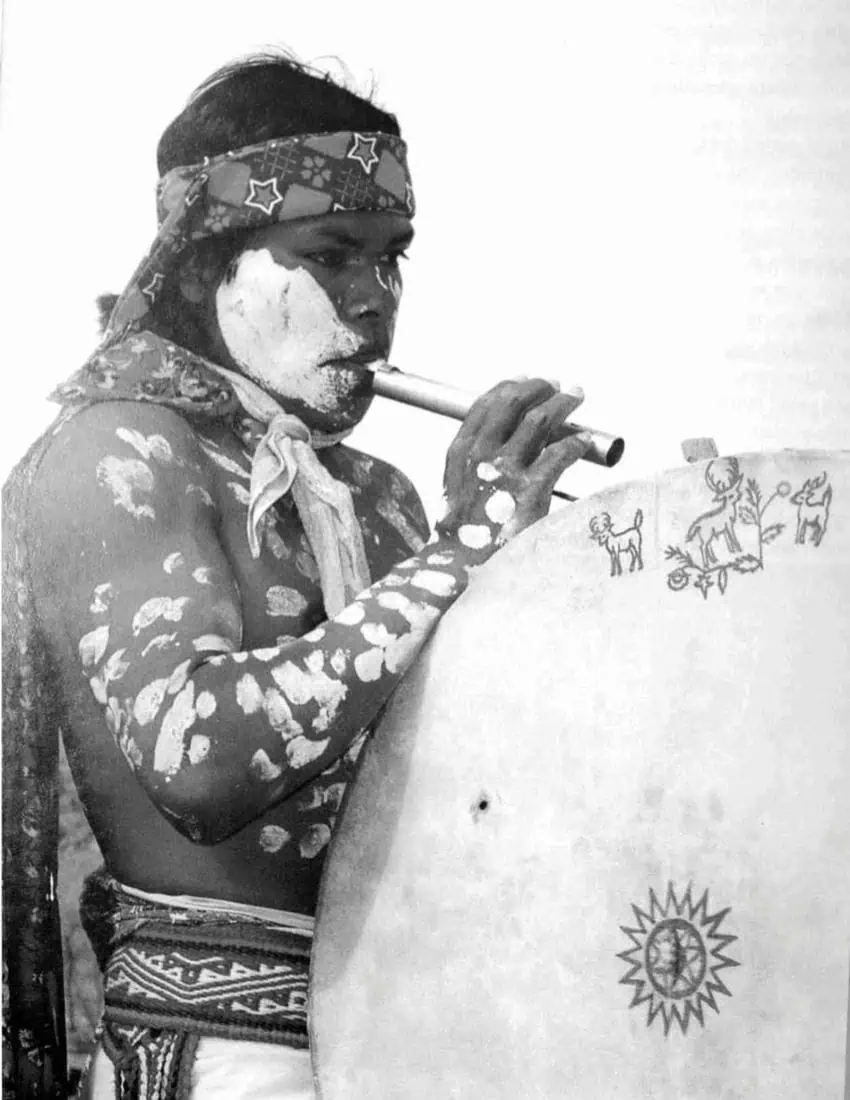

One of the most visually striking processions is the pintos dance, in which participants paint their bodies with small circles using lime (the mineral form of limestone).

To wrap up, participants burn a Judas effigy in a ceremony that symbolizes betrayal and the ultimate triumph of good over evil.

According to local customs, the local religious authority of the Rarámuri needs to grant permission to outsiders.

Penitence and purgatory in Taxco, Guerrero

Taxco is home to some of the most visually striking processions of the country: the procession of the blessed souls of purgatory.

Taking place on Holy Tuesday (April 15 this year), participants are divided into three groups that weave their way through the town’s streets: the cross bearers, the flagellants and the souls.

The cross bearers are typically men walking barefoot and bare chested, while they shoulder coils of thorny brambles weighing over 40 kilograms pressing into their skin that often causes it to bleed. The flagellants whip their own backs with nail-tipped scourges. The third group — women who represent souls — wear black cloaks and walk slowly, wearing heavy metal chains bound to their hands and feet.

The flagellants and the souls appear again the following day at the atrium of the church of Santa Prisca during a representation of Christ’s agony at the Garden of Gethsemane.

While some attendees get unsettled by the sight of the hooded figures and self-inflicted suffering, many others see these processions as a powerful expression of faith and a reminder of Christ’s agony.

Gabriela Solis is a Mexican lawyer turned full-time writer. She was born and raised in Guadalajara and covers business, culture, lifestyle and travel for Mexico News Daily. You can follow her lifestyle blog Dunas y Palmeras.