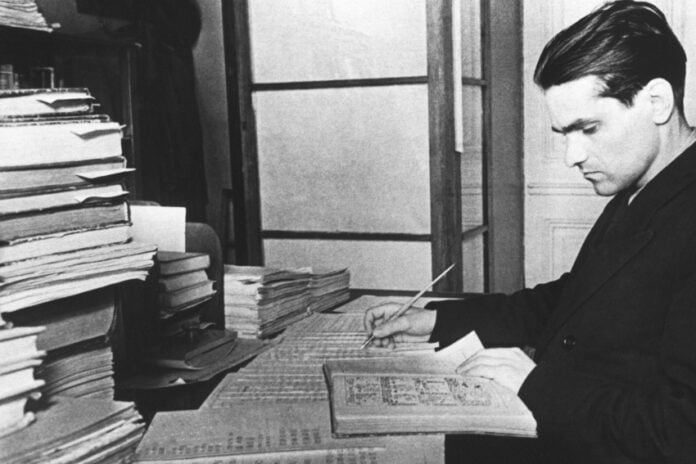

It’s 1952, and Western archaeologists are trekking through lush Central American jungles, searching for clues to unlock centuries of mystery surrounding the Maya civilization. Yuri Knorozov is sitting at his desk in a chilly Moscow, poring over ancient hieroglyphic texts and images, on the verge of a monumental breakthrough that would change history forever.

The Soviet linguist, known for his unconventional mind, had never seen a Maya ruin, never felt the humid air of the Yucatán, never touched an ancient stone carving. But from his remote office more than 10,000 kilometers away, Knorozov managed to crack the Mesoamerican code that had stumped scholars for centuries.

From WWII Berlin to Moscow: How war led to a breakthrough

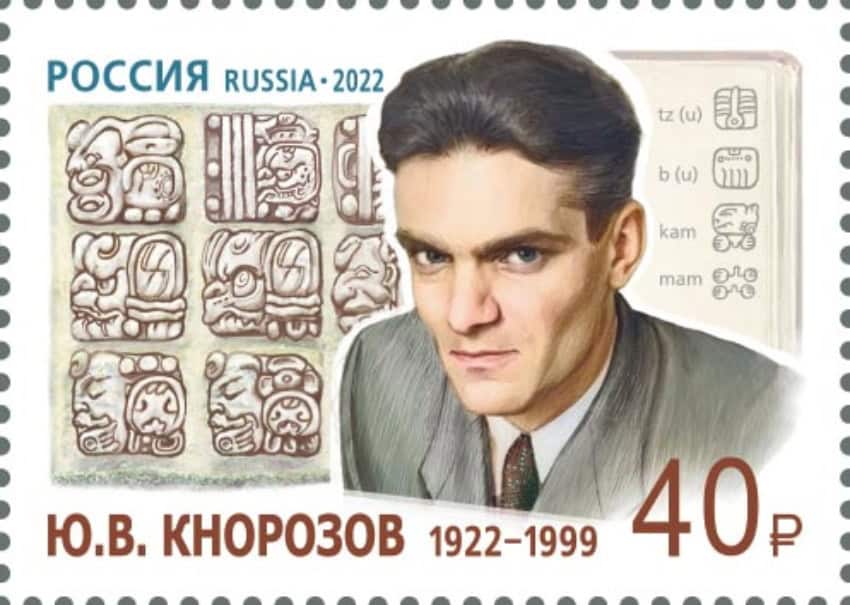

Born in the Soviet Union in 1922, Knorozov, a fair-skinned, dark-haired intellectual, spent his early 20s at the start of World War II hopping from village to village to avoid army conscription. Between relocations, Knorozov studied Egyptology at the local university.

He was eventually conscripted and sent as a Soviet artillery spotter to Berlin, where he stumbled upon something precious. Inside a crate of Nazi materials marked for destruction, Knorozov found a collection of rare reproductions containing three Maya codices. He took them home.

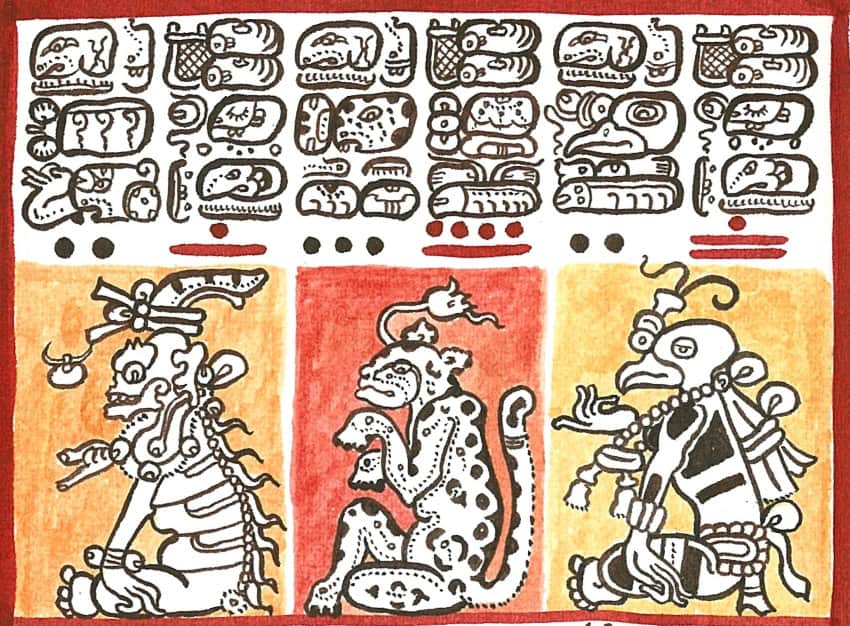

The codices consisted of three screenfold books with bark paper and coated with stucco. The Dresden Codex, at 74 pages, contained precise Venus tables, lunar eclipse cycles and ritual almanacs demonstrating the Maya’s sophisticated understanding of celestial mechanics. The Madrid Codex, the longest of the three at 112 pages, featured extensive almanacs and divinatory texts that showed the intertwining of Maya daily life with their complex calendar systems. The fragmentary Paris Codex, at just over 20 pages, offered crucial references to Maya mythology and new year ceremonies.

Back in Moscow after the war, Knorozov also worked extensively with a Spanish manuscript by Franciscan bishop Diego de Landa, called “Relación de las cosas de Yucatán.” This text, written in 1566, attempted to document Maya culture and writing by assigning each glyph to a letter of the Spanish alphabet.

While studying these materials, Knorozov came across an article by the German scholar Paul Schellhas entitled “Deciphering Mayan Hieroglyphs: An Unsolvable Problem?” The author dismissed Mayan written language as indecipherable. Many academics of the time accepted Schellhas’s conclusion.

Knorozov saw it as a challenge.

The mathematical method that decoded Maya hieroglyphs

Studying the codices in Moscow, Knorozov began to question the prevailing assumptions about Mayan writing. How could a civilization capable of producing such detailed celestial calculations possess an unsophisticated writing system? His in-depth analysis of de Landa’s work revealed two crucial errors. First, de Landa had tried to match Mayan symbols to Spanish letters, but with 355 symbols, it was clear that Mayan writing didn’t work like a simple alphabet. Second, he’d missed that the system was mixed: symbols could represent entire words (logograms) or syllabic sounds, depending on their position.

Knorozov developed a statistical approach that was revolutionary for its time: Working methodically through the codices, he counted symbol frequencies and tracked their positions. How many times did each symbol appear? Where in the text — at word beginnings, middles or ends? This positional analysis revealed patterns that previous scholars had overlooked, patterns that would prove crucial to unlocking the meaning behind Maya script.

His mathematical approach gave him confidence in his conclusions, but convincing the academic world would prove a different challenge entirely.

When Soviet science met Western skepticism

The academic establishment of the 1960s was in no way ready for a Soviet solution to their Western puzzle. Eric Thompson, the leading British Maya expert, blatantly dismissed Knorozov’s 1963 book “The Writing of the Maya Indians” as fundamentally flawed. Thompson’s skepticism carried weight, as he was the Western authority on Maya studies.

But this wasn’t just scholarly disagreement. Cold War tensions made Western academics suspicious of Soviet research. How could a linguist who’d never set foot in Maya territory, who worked from reproductions rather than original stones, crack a code that had stumped generations of field researchers? To many Western scholars, the idea seemed implausible.

Vindication finally came in 1973 at the Palenque Round Table conference. Thirty researchers — including art instructor Linda Schele and undergraduate epigrapher Peter Mathews — gathered to work on Mayan inscriptions. When they applied Knorozov’s methods to the Tablet of the 96 Glyphs, they achieved something remarkable: they deciphered actual names of Maya rulers, including the great king K’inich Janaab’ Pakal. Suddenly, the stories on Maya stones made sense, and the dates, dynasties and personal names would change the course of Mexican history. Thompson, his biggest rival, would die two years later without acknowledging Knorozov’s revolutionary contributions.

The man behind the discovery: Academic quirks and scholarly focus

Beyond his groundbreaking scholarship, Knorozov was a figure of fascinating contradictions. Described by colleagues as an introvert, he possessed a sense of humor that manifested in unexpected ways. His most famous quirk — it has been said that he listed his Siamese cat, Asya, as coauthor on academic papers — reflected the scholar’s playful approach to rigid academic conventions.

Knorozov maintained an intense work ethic, spending countless hours studying in institutions like the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Leningrad and the University of Moscow. His motivation came from intellectual challenge rather than conventional academic pathways, and when faced with the widespread idea that Mayan hieroglyphs couldn’t be cracked, he decided to solve an unsolvable problem.

Despite his revolutionary discoveries, he remained remarkably modest about his achievements. His personal life reflected the focused lifestyle typical of Soviet intellectuals: He got married, had a daughter named Ekaterina and a granddaughter named Anna and lived a life largely dedicated to his scholarly work. When he finally visited Mexico in the 1990s, colleagues noted his surprise at being received as a hero, suggesting a man more comfortable with codices than celebrity.

Knorozov’s triumphant Mexico visits

In 1990, nearly 40 years after his discovery, Knorozov finally traveled to see the Maya lands that had consumed his career.

Invited personally by the President of Guatemala, Vinicio Cerezo, Knorozov traveled first to Guatemala and then made three subsequent visits to Mexico, visiting the Maya ruins of Palenque, Mérida, Uxmal and Dzibilchaltún. He was greeted with great admiration and respect, celebrated as a hero for having unlocked one of the greatest historical and linguistic mysteries of the Americas.

The man who had given a voice back to the ancient Maya civilization was embraced by modern Maya communities and Mexican scholars. The Mexican government awarded him the Order of the Aztec Eagle in 1994, making him an honorary Mexican — a fitting honor for someone whose heart, he said, “always remained with Mexico.”

Knorozov died in Saint Petersburg in 1999.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog or follow her on Instagram.