The morning arrived fresh in Oaxaca, with that clean air that only exists in the first hours of the day, when the sun is just beginning to warm the streets and the hills surrounding the city. I climbed into the car with my camera slung over my shoulder and my heart filled with the anticipation that always precedes true encounters.

I didn’t know exactly what I’d find in San Antonino Castillo Velasco, a nearby town of Zapotec origin; all I had was a name — José García — and the promise of meeting a clay artisan whose story had reached me the way all good stories do: by word of mouth, wrapped in admiration and mystery.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

There is something sacred in the craft of clay, something that connects the artisan to the very origins of humanity. Clay was the first thing we shaped, the first thing we transformed into something more than mere matter.

When I arrived, the town was quiet. Some people were walking in the streets, dogs were dozing in the shade of the trees, and the smell of burning firewood hung in the air. I asked about José García, and everyone knew who he was.

The same woman, rendered again and again

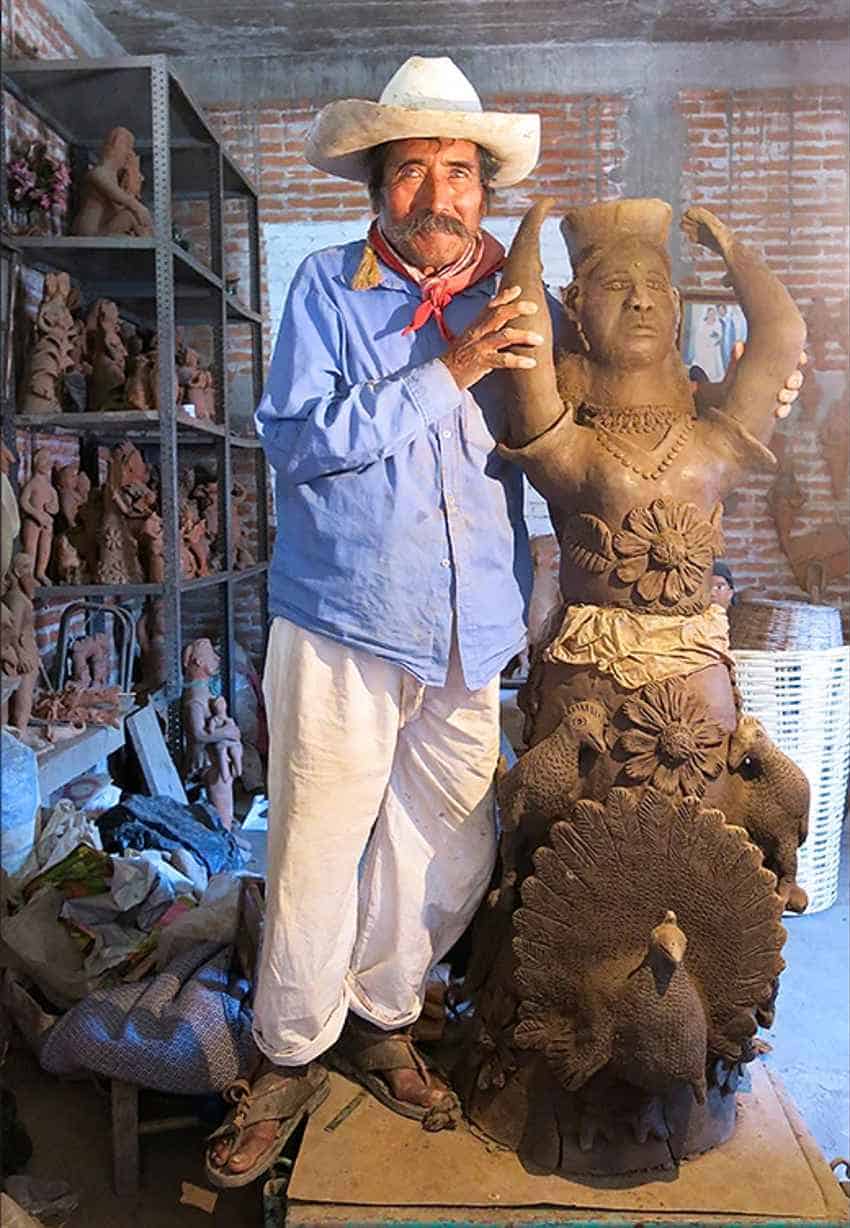

I knocked on the door, and a woman came out to greet me, her face lit up by a deep smile. She led me to her husband, who greeted us. His eyes, though open, had that opacity that betrays the absence of sight. José García, who lost his sight due to glaucoma, often known for his sculptures as “The Lord of the Sirens,” extended his hand to me with a warm smile, and in that simple gesture, I felt all his hospitality.

Under a corrugated metal roof that provided a shield from the sun but still let in the light, was José’s workshop. It wasn’t an ostentatious space, but it had that beauty that only places where things are created with soul possess. The house was large, and through the different rooms were wooden shelves filled with clay figures. Throughout the patio, pieces in various stages were freshly molded, still damp, air-drying, or already fired, bearing that terracotta hue.

But what caught my attention most was the repetition of these figures. Many of them depicted the same woman over and over, in different poses and dresses but always recognizable. Some stood with their hands on their hips; others were seated, as if resting after a long day; some carried pitchers or baskets.

There were dozens of them, each unique in its details but all sharing the same essence, the same spirit.

“She’s my wife,” José told me, as if reading my mind. His voice had that soft tone of someone speaking about the most sacred things. “I’ve been doing it for years.”

Sculpting by heart

He sat on his workbench, a low wooden seat polished by years of use, and held in his hands on the clay piece he had already shaped. He didn’t need to see to know exactly what to do. His fingers moved with a sureness that only muscle memory can provide, that wisdom that resides inside the body.

His hands worked as he spoke, kneading, shaping, smoothing. I watched as his fingers palpated the clay, recognizing every curve, every proportion. There was no doubt or hesitation in his movements. He knew every move by heart.

I remained silent, watching him work. There was something deeply moving about watching him bring the clay to life, creating the woman he loves over and over again. It wasn’t just craftsmanship; it was an act of devotion, a phrase made of clay and water, a way of speaking without words.

I raised the camera and began taking photographs. I captured his hands working the clay, the concentration on his face, the way his fingers moved with an almost dance-like grace. But above all, I tried to capture something intangible: the love that flowed from his hands into the clay, the devotion that transforms a simple lump of earth into a testament of gratitude.

Social anthropologist and photojournalist Ena Aguilar Peláez specializes on cross-cultural interactions within historical and cultural contexts. She writes about the environment, human rights, culture, and health.