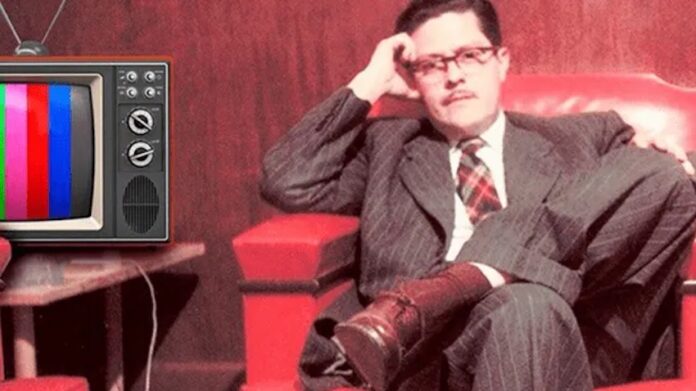

In Mexico, television remains king. Despite the global digital revolution, the glow of a TV screen still dominates Mexican living rooms. According to the country’s Federal Institute of Telecommunications, 91 percent of Mexican households own at least one television. YouTube, streaming platforms, and smartphones may nibble at its audience, but television has held its throne for more than seven decades.

The story of how television became so central to Mexican life begins with a young man who decided that black-and-white was simply not enough. In the 1940s, a self-taught engineer from Guadalajara would create a device that changed not just Mexico, but the way the entire world sees itself.

Mexico at the dawn of the television age

Picture Mexico in 1940: just three decades removed from the Revolution, eager to project an image of modernity. Mexico City’s population had barely reached 1.7 million; electric streetcars were replacing mule-drawn trams, and the Federal Electricity Company (IFE) — created only three years earlier — was bringing power to more and more homes.

Refrigerators, radios, washing machines, status symbols as much as conveniences, were finding their way into the country’s wealthiest households. Yet the medium that would transform Mexican culture was still a curiosity: television.

Entrepreneurs at radio giant XEW-AM were already leading broadcasters in Mexico, as the government envisioned a BBC-style channel run by the National Institute of Fine Arts, mixing culture with the occasional political message. Mexican engineers had been experimenting with television since 1928, and by 1931, they imported the first sets and cameras for the nation’s inaugural broadcast.

Among them was a teenage apprentice who would become a national icon: Guillermo González Camarena.

The boy genius

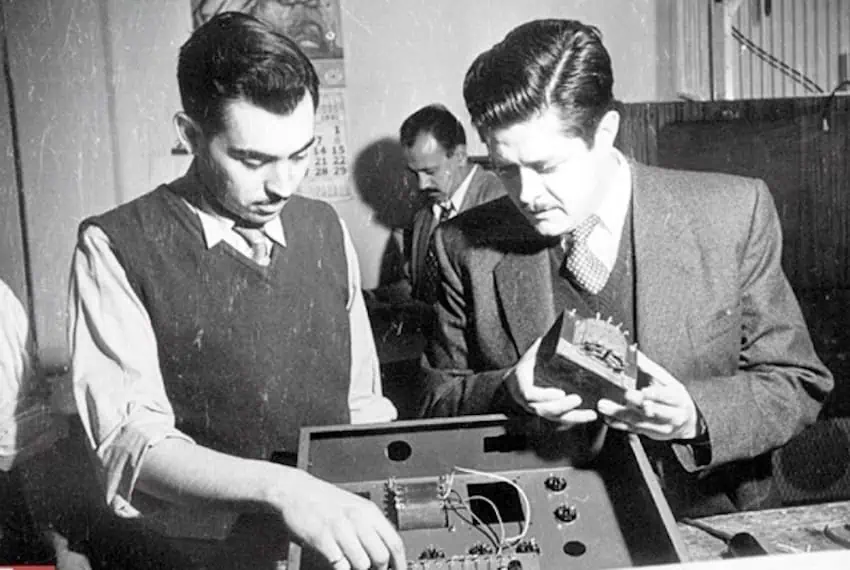

Born in 1917 to a middle-class family, Camarena displayed an irrepressible curiosity from childhood. By eight, he was dismantling and improving any electrical gadget he could get his hands on. At seventeen, combing through the markets of Tepito and La Lagunilla for discarded components, he built an entirely electronic television camera from scratch. He also began producing experimental programming, broadcasting to an almost non-existent audience.

His work caught the attention of then-President Lázaro Cárdenas, who in 1935 granted him access to government radio studios to further his research. Television at the time was a luxury, its sets bulky and expensive. But Camarena’s ambitions reached beyond wider access. He wanted to add something the world’s television pioneers had not yet perfected: color.

Bringing color to a black and white world

In the 1930s, moviegoers had already marveled at Technicolor films, so the idea of color television was not science fiction — it was an inevitability. What was missing was the technology to make it affordable and compatible with existing systems.

In 1939, Camarena invented it: the “Trichromatic Sequential Field System” (STSC). Using synchronized spinning discs in both cameras and TV sets, his method captured and displayed red, green, and blue fields in quick succession. The eye blended these fields into full-color images — vivid and sharp — without changing the existing broadcasting infrastructure.

It was brilliant in its simplicity, and revolutionary in its implications. In 1940, he patented the system in Mexico; two years later, in the United States. He was just 23 years old, holding the world’s first patent for a color television system, having beaten Hungarian-American rival Peter Goldmark to the patent office by 19 days.

American companies tried to buy the invention, but Camarena refused. He wanted Mexico to be a technology exporter, not merely a consumer.

The color television wars

In 1950, CBS in the United States adopted Camarena’s system for its color broadcasts. But RCA — having sold more than ten million black-and-white sets incompatible with the technology — fought back. Legal and market pressures kept the system from taking root in the U.S., but in Mexico, Camarena thrived.

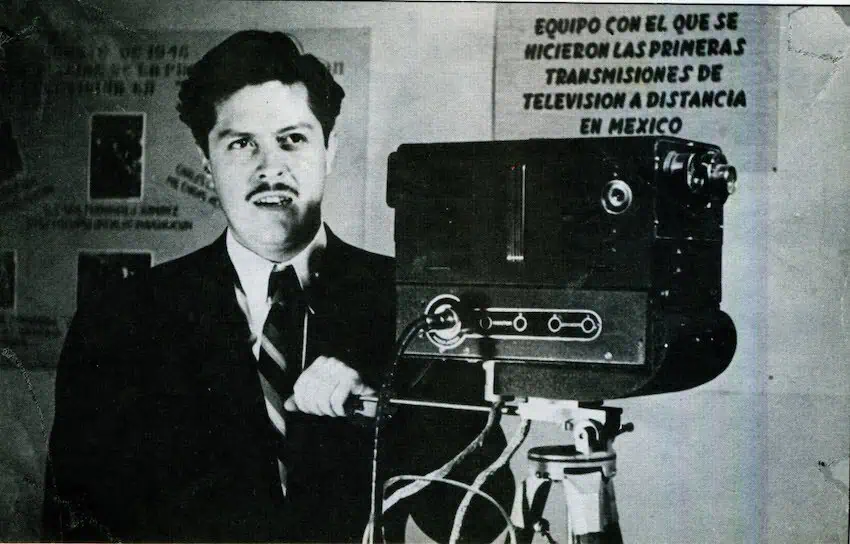

By 1946, he was transmitting experimental broadcasts from his home. Knowing few could afford a set, he installed closed-circuit televisions in department stores so customers could see themselves on screen — a clever preview of what was to come.

Building a television industry

On August 31, 1950, Camarena and media magnate Rómulo O’Farrill launched Channel 4. Its first broadcast was dedicated to President Miguel Alemán’s State of the Union address, followed by Mexico’s first televised newscast.

A year later, Emilio Azcárraga Vidaurreta received the concession for Channel 2, which would grow into Televisa, the country’s most influential network. These early broadcasts were still in black and white, however.

In 1950, Camarena began operation of Channel 5, dedicated to educational and cultural programming. When Azcárraga acquired the channel in 1955, it pivoted to children’s content, reflecting Camarena’s lifelong belief that television should inspire young viewers into education and culture.

By 1960, he was celebrated as the father of Mexican television. But his true breakthrough came on February 8, 1963, when Channel 5 aired “Paraíso Infantil” (Children’s Paradise) in full color. Nearly 24 years after inventing the STSC, Camarena had made Mexico the fourth country in the world to broadcast regularly in color.

A life cut short

On April 18, 1965, Camarena died in a car accident while returning from inspecting a transmitter in Veracruz. He was 48. At the time of his death, he was still working on projects that would have shaped Mexico’s role in global broadcasting, including preparations for the 1968 Olympics.

His loss was felt not only in Mexico but across the international scientific community. Yet his influence was far from over.

The enduring color revolution

From the 1950s onward, television transformed Mexican life. It changed domestic architecture, redefined leisure, and created a shared visual culture.

His invention traveled far beyond Mexican living rooms. In the late 1970s, NASA adapted his STSC system for the Voyager missions, which returned humanity’s first color images of Jupiter. The same principle that lit up Mexican children’s shows in 1963 was sophisticated enough to capture the planet’s massive, swirling storms from millions of miles away.

A Digital Legacy

In a way, if you are reading this on a screen, watching Netflix tonight, or video-calling a loved one, you are benefiting from a chain of invention that began with a teenager rummaging through flea market stalls in 1930s Mexico City, searching for the parts to build something no one had imagined.

Camarena’s story is more than his technical achievements. It’s about the belief that innovation can — and should — emerge from anywhere. His refusal to sell out his invention to foreign corporations was not just patriotism; it was a declaration that Mexico could lead, not follow, in the technological future.

María Meléndez is a Mexico City food blogger and influencer.