One of the most indelible flavors of my childhood is Boing! — a juice drink that seemed to

shadow every moment of daily life. It nestled in lunchboxes, accompanied our favorite

tacos, and appeared unfailingly wherever families gathered. Long before we understood

the environmental costs of plastic bags and straws, pouring a Boing! into a thin, crystal

clear plastic bag was a small ritual of play and nourishment, a tactile delight that defined

an era.

So, a few weeks ago, when I read that Boing! — after 80 years of being woven into the fabric of Mexican life — may soon disappear under legislation that raised the price of sugary beverages, the news struck with a familiar ache. The sadness came not only from

nostalgia but from the belief that behind this policy lies a fundamental miscalculation.

You can educate the public about balanced diets and curb aggressive advertising, but

punitive measures rarely unravel problems with deep cultural and logistical roots.

Pascual–Boing

Its story starts in the late 1930s and early 1940s, when Rafael Víctor Jiménez Zamudio

founded a modest company selling popsicles and bottled water. But Don Rafael had

always harbored a larger ambition: to offer refreshing beverages made with real fruit.

The company opened its first facilities in the San Rafael and Tránsito neighborhoods of

Mexico City. Its first major success was Pato Pascual, a soda marketed as the first

100% Mexican soft drink made with fruit. By the late 1950s, the company introduced

Lulú, another product crafted for a growing urban market seeking quality and flavor at

an accessible price.

By 1960, Pascual was thriving, expanding into other Mexican states and even reaching

the United States and Japan. It also launched Boing!, a non-carbonated drink made with

natural pulp and free of preservatives. Distinct from the rest of the brand’s

portfolio — and from its competitors — Boing drew on the cultural memory of aguas

frescas, tapping into Mexico’s deep affection for natural fruit beverages. Don Rafael, still

pursuing durability and innovation, approached the Swedish company Tetra Pak and

secured exclusive rights to its now-iconic triangular packaging, making Pascual the first

and, for a time, the only brand to use what was then considered the most hygienic

packaging available.

By the decade’s end, Pascual purchased a plant from Canada Dry and took over its

production lines. But the relationships with both Tetra Pak and Canada Dry would

fracture after a workers’ strike erupted.

La Guerra de los Patos

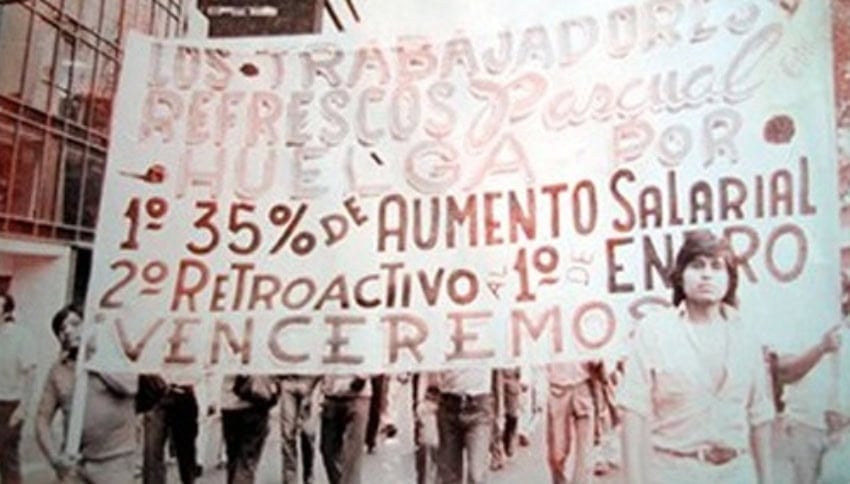

One of Mexico’s defining labor movements was led by Pascual Boing’s workers. In March

1982, amid a national economic crisis, the government decreed mandatory wage increases of 10%, 20% and 30%. Many companies complied; the Pascual Boing family

did not.

Frustrated by precarious working conditions, like 12-hour shifts, employees sought

support from the Mexican Workers’ Party. With its guidance, they launched a strike on

May 18, 1982, and shut down both the plants in Mexico City. Don Rafael assumed they

would eventually return. They did not.

On May 31, he made the unthinkable decision: he ordered that gunfire be opened on

the demonstrators. Two people were killed. Seventeen were wounded. Public outrage

surged. Workers, joined by allies, occupied the offices of the Federal Conciliation and

Arbitration Board. Eventually, the movement prevailed.

In August 1984, in an unprecedented resolution, it was agreed that the strike and the

so-called “Duck War” would end with the creation of a cooperative. The assets of

Refrescos Pascual S.A. would be transferred to its workers.

Pascual Workers’ Cooperative S.C.L.

On May 27, 1985, the newly formed Cooperative launched the Aguascalientes Project.

Eight trucks traveled to the Aguascalientes plant — where Boing! was still being

produced — to load products and return to what was then the Federal District, with the

intention of reopening operations.

The workers reclaimed control of the production process, not by abolishing hierarchy

but by humanizing it. Critical decisions were now made in assemblies where every

member had a voice.

They resumed activities with a renewed purpose: to craft natural, healthy, nourishing

beverages that could satisfy consumers of all ages, within a dignified and equitable

workplace.

Today, the cooperative employs 4,500 people across multiple Mexican states. It stands

as an exception in an industry dominated by multinational corporations, reinvesting

profits into cooperative members and the agricultural communities it supports. Its

financial philosophy is modest by design: prioritize employment and affordability over

profit maximization.

Adapting to a modern lifestyle

For more than a decade, Cooperativa Pascual has contended with policy initiatives

meant to limit sugary drink consumption. When the first tax on sugary beverages was

implemented in 2014, Boing!’s sales fell by 50%. Recovery took years, as the

cooperative chose job preservation over aggressive cost-cutting.

Since then, additional tax increases and regulatory measures have continued to weigh

heavily on production and distribution. To tackle this impact, they have added Agua

Pascual and Leche Pascual to their product lineup. Yet Boing!, Lulú sodas, Pato

Pascual and Mexicola remain their most popular products.

Boing and street food

Street food has been a cornerstone of Mexican life since pre-Hispanic times, yet Boing!

stands out as the first mass-produced commercial beverage to integrate organically into

this popular gastronomic ecosystem without flattening its diversity. At food stalls across

the country — though less frequently now than in years past — you can still find Boing! as

the traditional companion to tacos, gorditas, soups, panuchos and an endless array of

antojitos.

But Boing now faces an unprecedented threat. In March 2025, the Mexican government

launched the “Healthy Life” program, banning sugary drinks from all schools nationwide

and eliminating a significant segment of Boing!’s traditional market, which is a great

initiative, to be fair.

In October 2025, Congress approved a dramatic increase to the Special Tax on

Production and Services (IEPS) for sugary drinks. The tax will rise from 1.64 to 3.08

pesos per liter in 2026 — an 88% jump. Drinks with non-caloric sweeteners will face a tax

of 1.5 pesos per liter.

For a cooperative with just 2% of the national soft drink market that is competing against

Coca-Cola’s approximate 60% and PepsiCo, this escalation is disproportionate and

potentially catastrophic. Pascual’s leadership warns sales could shrink by as much as

60%, forcing the suspension of a new plant slated to open in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas,

in 2026. A 900-million-peso investment is now frozen.

The paradox of public health legislation

The tragedy here is that the legislation threatening Boing! was designed in the name of

public health, to combat Mexico’s staggering rates of childhood obesity. According to

the National Health and Nutrition Survey 2020–2023, 5.7 million children ages 5–11 and

10.4 million adolescents ages 12–19 live with obesity.

But the law lacks the nuance to distinguish between different production models. Coca-

Cola and PepsiCo can rapidly reformulate their beverages with synthetic sweeteners

and qualify for the lower tax rate of 1.5 pesos per liter. Pascual, operating under a

cooperative ethos and cultural mission, remains committed to natural cane sugar and

rejects high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), the cheaper alternative used by the U.S.

multinationals.

This commitment has real consequences. HFCS is inexpensive and helps large

corporations absorb tax burdens. Mexican cane sugar is costlier but nutritionally

superior — and central to Boing’s identity as an authentically Mexican beverage. Pascual

requested that Congress create differentiated tax mechanisms or incentives for social-

economy companies using natural and domestic ingredients. The plea went

unanswered.

Pascual’s leadership is weighing a complete reconfiguration of its products — or the

possibility of closing operations altogether. For the cooperative’s 4,500 workers and the

livelihoods of 785 cooperative members hang in the balance, alongside thousands of

sugarcane producers who rely on Pascual as a major buyer. Senator Carolina Viggiano

has warned that Mexican cane growers have already begun reducing supply because it

is no longer viable without large, consistent purchases from Pascual. This would mean

job loss in a sector where cooperatives already occupy a precarious position.

A political and cultural crossroads

In 2025 and 2026, Boing! stands at an economic, political and cultural crossroads. So, the fundamental question emerges: Is Mexico prepared to sacrifice the icons of its

social economy and popular gastronomy on the altar of well-intentioned but blunt

regulation — one that cannot distinguish what deserves protection (cooperative labor,

national production, cultural tradition) from what should truly be discouraged?

As a ’90s kid who grew up on radioactive chips, fluorescent ICEEs, candies that

probably violated several laws of physics, Morgan & Drake sodas with what looked like

floating confetti, and liters upon liters of Boing! as the perfect companion to my taquitos,

I learned a crucial truth at home — one that shaped both my health and my relationship

with food: having a treat now and then is perfectly fine, so long as you maintain a

balanced diet.

Yet maintaining a clean, healthy diet is far more difficult for most Mexicans, for reasons

that run deep in culture, infrastructure and economics — reasons that I’ll explore in future

articles.

Maria Meléndez is an influencer with half a degree in journalism