Throughout my literary explorations, I have long professed my belief that literature is a

portal to understanding the world — a means of grasping how other cultures perceive

existence, mortality and meaning itself. Among the authors who fundamentally

reshaped my adolescence and early adulthood was José Emilio Pacheco. His

novel “You Will Die Far Away” became transformative. I have returned to it three times.

Yet Pacheco’s story defies the romantic archetype we construct around artists. He was

not born into revolution’s tumult, nor shaped by privation or trauma. And yet his

literature exhales melancholy — a profound, almost physical sadness that permeates his

work. Those who knew him well describe a paradox: a serious, reserved figure whose

wit was sharp and whose kindness was genuine. He was a man consumed by music, a

passion he channeled through poetry into something luminous.

José Emilio Pacheco Berny

José Emilio Pacheco Berny arrived in Mexico City on June 30, 1939, at a moment when

his nation was constructing the fiction of modernity and industrial progress. His

childhood was neither desperate nor ordinary. His father was a lawyer and an accountant.

His family lacked wealth but overflowed with intellectual capital. Their home became a

salon where the era’s great minds gathered — José Vasconcelos, Juan de la Cabada,

Martín Luis Guzmán, Julio Torri — figures who would later define Mexican letters.

It is impossible to overstate what such an environment bestows. Pacheco was

intellectually precocious, a voracious reader from childhood. He devoured the Hispanic

American canon: Borges, Alfonso Reyes. But he also looked beyond his own tradition,

absorbing the world’s literature with something approaching hunger.

His father had other plans. Hoping to pass on his law practice and clientele, he steered

his son toward the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. For a time, Pacheco

complied. But at nineteen, he abandoned jurisprudence for literature, a choice that

must have bewildered his father, though perhaps not surprised him.

The early break came through Carlos Fuentes, who recognized Pacheco’s gifts and

opened doors to literary magazines and supplements. But it was Fernando

Benítez — that colossus of Mexican cultural life, founder of the magazine La Cultura en

México — who genuinely transformed Pacheco’s trajectory. Through Benítez’s pages,

Pacheco found his generation, and his generation found him.

A man of his generation

Like his literary contemporaries, Pacheco interrogated nationalism, wrestled with history,

pondered the city, death, memory and truth. What distinguished him was his refusal of

ornament. His language was direct, austere. His critical eye missed nothing. And he commanded, with equal mastery, nearly every literary form: poetry, short stories, novels,

essays.

This eclecticism mattered. It meant that whatever consumed him, and he was

consumed by much, could be channeled through multiple prisms.

What should you read by Pacheco?

Regrettably, only two of Pacheco’s major works exist in English translation: “Battles in

the Desert” (1981), a novel, and “You Will Die Far Away” (1967), likewise a novel. The

paucity of English translations is, frankly, a failure of the American literary

establishment.

‘You Will Die Far Away’

The title itself contains a tragedy. The novel was once rendered in English as “You Will

Die in a Distant Land,” a literal rendering that misses the philosophical thrust entirely.

The book speaks not merely of geography but of dislocation in time, being and

consciousness. It evokes war, humanity and the religious questions that torment us.

The novel unfolds against the Holocaust and the persecution of Jews — historical trauma

that Pacheco approaches obliquely, allowing readers to complete the narrative

themselves. We witness not the event but the impossibility of narrating it. We confront,

through fractured passages and deliberate silences, our own capacity for cruelty. The

book demolishes linear time, fracturing itself into temporal shards that force the reader

to pause, recalibrate and begin again.

Critics called it experimental. They were correct, though “ahead of its time” hardly captures it. Pacheco was reinventing the novel’s very structure decades before fragmentation became fashionable.

‘Battles in the Desert’

This novel and the song it inspired, composed and performed by Café

Tacvba, became the anthem of an entire Mexican generation. Through Carlitos, a boy

in La Roma during the waning 1940s, and his obsessive love for his schoolteacher

Mariana, Pacheco constructs something larger: a critique of Mexico’s contradictory

modernization project, its promises and failures.

The book functions as both an elegy and a historical document. Pacheco mourned the

Mexico City that he knew, even as he documented its metamorphosis. Read it now, in the

21st century, and you will feel the weight of his nostalgia — and perhaps share his

alarm at what his neighborhood has become.

Short stories

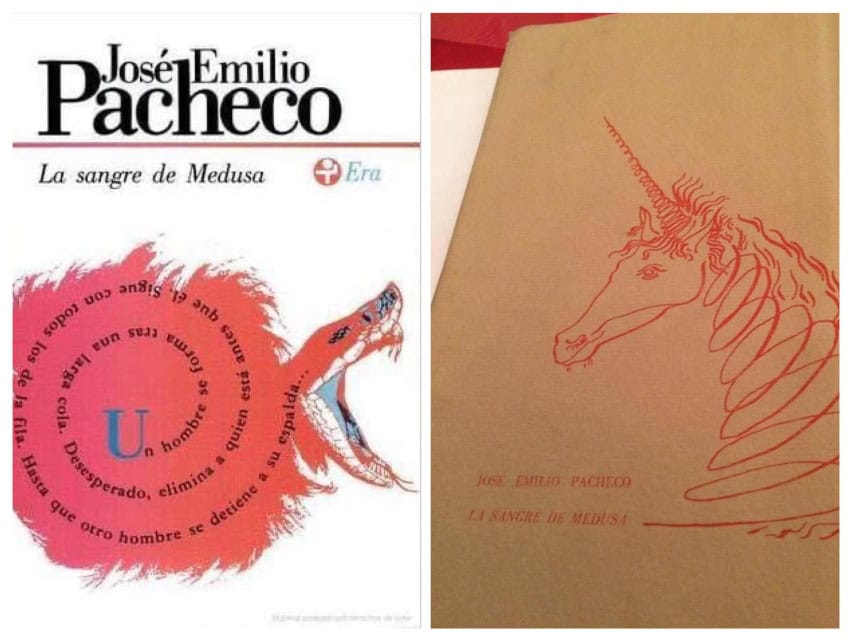

“Medusa’s Blood” inaugurated Pacheco’s career in the form. His short fiction is indispensable. Despite their brevity, these stories contain the full spectrum of his obsessions: time, death, the city, love, betrayal. More importantly, they exemplify his direct, unadorned style — free from the baroque verbosity that characterized so much Mexican prose. This clarity is revolutionary.

Poetry

Literary scholars regard his verse as poesía perfecta, perfect poetry. Even when he

abandoned traditional metrical forms, his lines retained an almost mathematical

precision. His metrics were flawless.

His poems are acts of homage to Mexican writers and foreign masters alike. But their

real power lies in his prophetic sensibility. In the late 1960s and 1970s, when social

movements convulsed Mexico and inequality deepened, Pacheco foresaw poetry’s

impending exile from public life, its transformation into a luxury good, almost a

perversity, within modernity’s cold calculus.

Open any translated collection and you will find the same preoccupations recurring:

time’s passage, mortality’s inevitability, the nature of loss. His poems do not console;

they educate. They teach us to see the world anew, to live with greater presence. Yet

beneath this contemplative surface lies critique — a running commentary on the societal

pathologies of the 20th century’s second half.

The “New Zoology Album,” created in collaboration with the painter Francisco Toledo,

holds particular resonance for me. My father gave it to me in childhood, when I could

barely decipher the poems. Yet it was through that book that I first fell in love with art

itself. The memory alone justifies its existence.

The translator who claimed he did not translate

Pacheco insisted he was not a translator but a recreator. Yet if Spanish readers possess

exemplary translations of T.S. Eliot, Tennessee Williams, Oscar Wilde and Samuel

Beckett, they owe this abundance to him. He believed, with an almost religious

conviction, that language must never be a barrier to literature. His translations won

awards and they opened Spanish America to foreign voices.

In interviews, Pacheco articulated something crucial: translation is as creative an act as

writing a novel. Selecting the precise word to honor the original’s meaning is as difficult

as inventing an entire narrative from nothing.

“Cómo es” (“How it is”) by Samuel Beckett, published in 1966 by Joaquín Mortiz, stands as

his masterwork in the form. Finding a copy in a contemporary bookstore is impossible,

though copies from that era remain affordable. If your Spanish permits, seek it out.

Cultural promoter and diffuser

No one asked me, but I believe Pacheco’s greatest love was knowledge itself — culture in its broadest sense. This conviction animated his journalism.

In Excélsior and Proceso, he wrote with a cultural lens, wielding literary criticism as a

tool for political commentary, resurrecting forgotten moments and figures, dismissed

movements.

He wrote extensively about Jorge Luis Borges and Mexican Modernism — artistic

movements that opposed nationalism and were consequently erased from official

histories. Pacheco rescued them from oblivion, restored them to view. In doing so, he

performed an act of cultural archaeology that still resonates.

A legacy of dissent

Pacheco accumulated honors during his lifetime. Yet he seemed uncomfortable with

acclaim, as though he doubted his own worth. He remains one of Mexico’s greatest

writers, nonetheless.

Across more than thirty works — excluding translations, screenplays and the countless

columns scattered across newspapers and magazines — he maintained a consistent

stance: critical, skeptical, alert to power’s abuses. And always present was his love for

language itself, for the precision and music of words arranged in sequence.

His style spoke to a generation distrustful of grand narratives and nationalism, a

generation that turned inward toward the self, toward the universal experiences of love,

fear, death, uncertainty and the particular Mexican experiences of crisis and nostalgia.

In Pacheco’s work, they found validation.

Reading Pacheco means witnessing Mexico through a dual optic: love and critique

simultaneously. He was enamored with his city, its streets and history, yet never blind to

the devastation modernization wrought. He contained contradictions. He was

perpetually dissatisfied, rewriting his work with each new edition, never quite satisfied

that he had said what needed saying.

‘Alta Traición’ (‘High Treason’)

I conclude with Pacheco’s most devastating poem — what follows is, admittedly, an

imperfect rendering into English. Yet it captures something essential about Pacheco’s

posture toward nationalism, government, homeland and love:

No amo mi Patria.

Su fulgor abstracto

es inasible.

Pero (aunque suene mal) daría la vida

por diez lugares suyos, cierta gente,

puertos, bosques de pinos, fortalezas,

una ciudad deshecha, gris,

monstruosa,

varias figuras de su historia,

montañas

(y tres o cuatro ríos).

I do not love my Fatherland.

Its abstract glow

is elusive.

But (although it sounds bad) I would give my

life

for ten of its places, certain people,

ports, pine forests, forts,

a torn city, gray, monstrous,

various figures from its history,

mountains

(and three or four rivers).

This poem has inhabited my thinking for years. In it, I have repeatedly found myself. Yet

I have also questioned it, interrogated it, resisted it. That Pacheco provokes such

reactions, even now, long after his death, is perhaps the truest measure of his

achievement.

Maria Meléndez is an influencer with half a degree in journalism