In 1920, close to the end of the Mexican Revolution, General Álvaro Obregón made a move that would have a significant impact on Mexico’s political history but also its cultural history — a move that changed art indelibly in Mexico, as well in the world.

In that year, Obregón overthrew President Venustiano Carranza, was elected president himself and then set about fomenting a national artistic and cultural shift in Mexico, the remnants which still can be found today.

Obregón’s coup was the culmination of a decade of civil war that had seen constant military battles, ever-changing factions and armies and a revolving door of leaders since 1910.

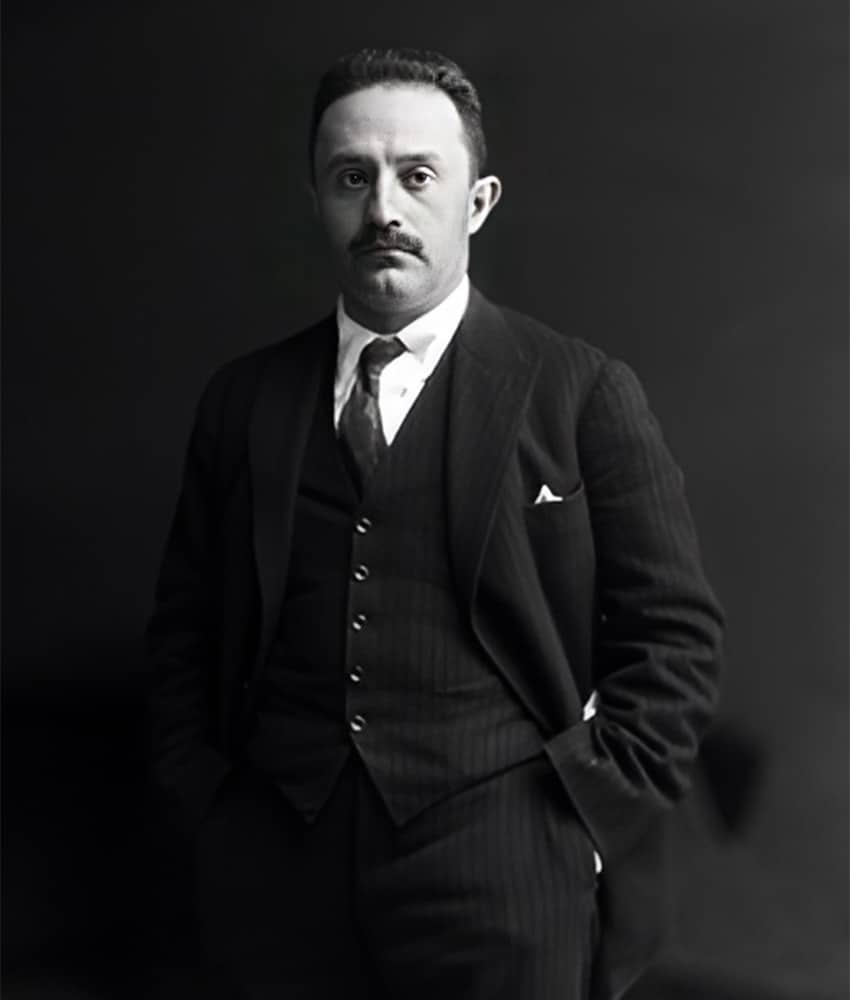

Upon being officially elected president in December 1920, Obregón tasked his minister of education José Vasconcelos with increasing literacy and forging what was seen as a much-needed sense of national and cultural unity.

Vasconcelos’s idea was to portray the revolution’s history in public spaces, using a visual language that would teach Mexicans about the revolution and instill national pride in their indigenous heritage.

During Obregón’s presidency, Vasconcelos mobilized creatives of all types — artists, musicians, singers, writers — to help forge this new identity, one in which Mexico’s indigenous past would be glorified and its colonial legacy condemned.

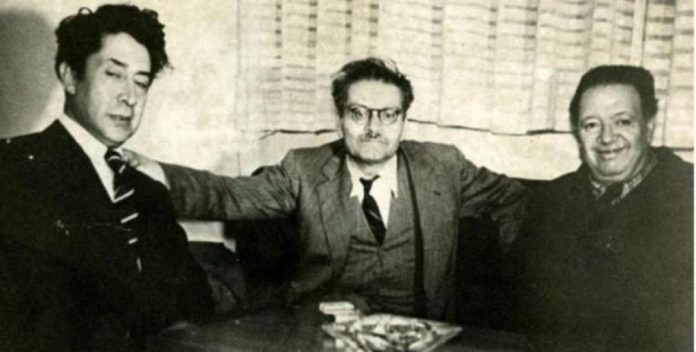

Three of the most famous of those creatives, muralists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros — the founders of the Mexican Muralist Movement and known as “Los Tres Grandes” (The Big Three) — would forever impact Mexico’s art, as well as artists worldwide.

Before Obregón came to power, Mexico was already experiencing a cultural renaissance, inspired by opposition to Díaz’s government. José Guadalupe Posada, for example, created his iconic figure later known as La Catrina to mock society’s pro-European cultural pretensions under Díaz’s leadership.

Posada, Orozco, Rivera Siquieros were among many artists already looking closer to home for a uniquely Mexican artistic style when they linked themselves with Obregón.

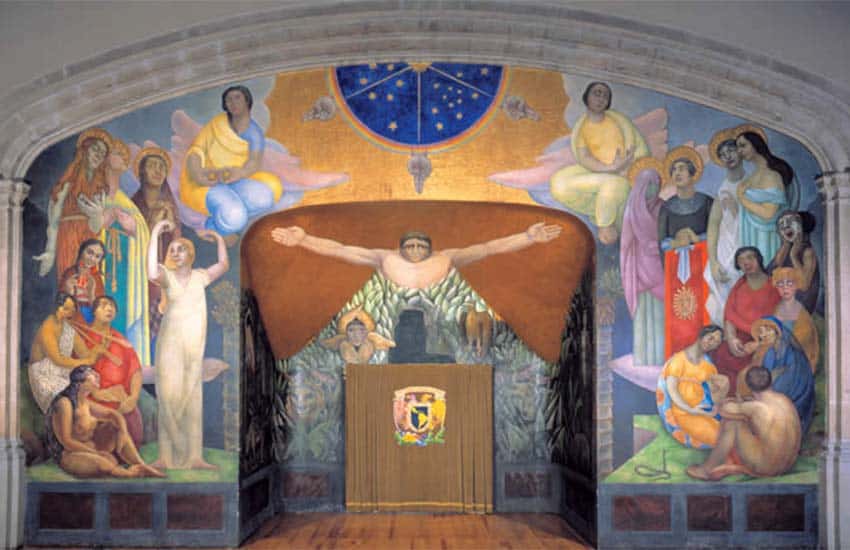

The Big Three were all commissioned to paint the first Obregón government fresco murals at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City in the early 1920s. Rivera’s “Creation,” the first of them, can still be seen today in Mexico City. He portrayed the Mexica as a great empire whose achievements were to be glorified.

Novelist John Dos Pasos, bemoaning the state of modern art in the United States, said at the time that “Going to see the paintings of Diego Rivera in the courts of the [Public Education Ministry] straightens you out a bit … If it isn’t an [art] revolution in Mexico, I’d like to know what is.”

Many of the works Los Tres Grandes did for the Obregón government are still visible in Mexico’s cities today, and most of them are accessible to the public. Here’s where to see some of them:

- Two of Rivera’s most famous government-commissioned murals reside at the National Palace and the former National Preparatory School. The National Palace’s stairway mural, “The History of Mexico,” relates the history of the Mexican people in three parts. Rivera’s “Creation” is still at the former National Preparatory School, now a cultural center owned by UNAM and known as the San Ildefonso Building.

- Siqueiros painted the massive mural “Del “Porfirismo a la Revolución” (From Porfirism to the Revolution) in Chapultepec Castle. A visual history of Mexico from Díaz’s dictatorship to the Revolution, it contrasts decadent iconic European imagery surrounding Díaz with images of Mexicans living in slavery and ignorance. It also contains phrases connected with the Revolution uttered by leaders such as Francisco Madero and Ricardo Flores Magón.

- Orozco’s murals can be seen at the former Hospicio Cabañas, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Guadalajara. Once a massive hospital and orphanage, the artist’s 57 murals there take aim at authority figures and depict Mexican history as a brutal, bloody struggle. There’s also his “Reconstruction,” painted in 1926 in what is today Orizaba, Veracruz’s Municipal Palace.

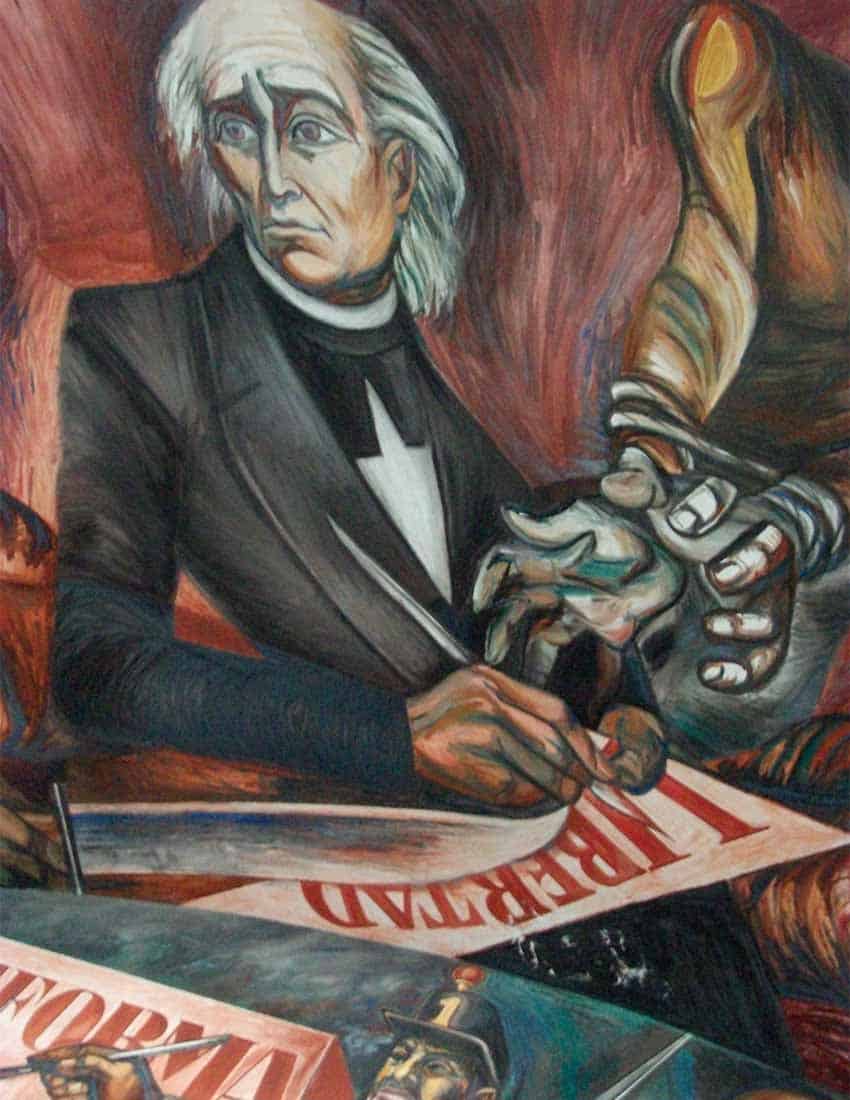

- A smaller but impressive collection of Orozco’s work can be found in Guadalajara’s Municipal Palace, including several well-known murals celebrating Father Hidalgo. Above the main staircase is a mural depicting Hidalgo wielding a flaming torch to ignite the independence movement. In the Chamber of Deputies, another depicts Hidalgo liberating the Mexican people by signing the word “freedom” in deep bloody red, suggesting the human cost of the independence movement.

- Murals by all three artists are also prominently displayed on the first floor of the main hall of Mexico City’s Palacio de Belles Artes (Fine Arts Palace) and at the San Ildefonso Building. There are also several other works by Mexican artists who were commissioned to paint murals as part of the program.

Vasconcelos and The Big Three and their contemporaries successfully tackled the difficult task of forging a Mexican identity, presenting the people with a national identity and history that glorified its indigenous roots in a way that has endured.

They also made an indelible impact outside Mexico: they are credited with helping revive the use of frescoes in modern art and changing the public’s perception of art in the U.S. and elsewhere — taking it out of museums and into public spaces. They also inspired the United States’ Depression-era Works Progress Administration (WPA) arts programs, which funded creatives to document U.S. daily life and the cultural expression and traditions of average people.

But ultimately, Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros created magnificent murals that will always belong to the Mexican people, who can visit them whenever they wish to remind themselves both of the Revolution and of the glory of their indigenous past.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán last year and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.