There are many ways to get to know a country: through its food, its music and its politics. But literature always struck me as the truest way in. Even when a story is invented, the way its characters speak and the way its landscapes are drawn reveal the habits, fears, and humor of a people. Truman Capote gives us one map and Jane Austen gives us another. In Mexico, Juan Rulfo gives us perhaps the starkest and most unforgettable map of all.

He left behind scarcely more than 350 pages. Yet in them — “El llano en llamas” (The Plain in Flames, 1953), “Pedro Páramo” (1955), and the screenplay-novella “El gallo de oro”’ (The Golden Rooster, 1964) — he conjured a rural Mexico scorched and silent, abandoned by the Revolution, peopled by voices both living and dead. These slim volumes altered the trajectory of Mexican literature forever.

Mexico in the aftermath of revolution

The landscape of Rulfo’s youth — and later of his fiction — was shadowed by the Cristero War, the bloody conflict (1926–1929) that erupted after the revolutionary state moved to curtail the Catholic Church. Outdoor masses were outlawed; priests were stripped of political rights; church property was seized. In a country where faith had long controlled daily life, the closures sparked rebellion. Under the cry “¡Viva Cristo Rey!” tens of thousands rose against the government. Roughly 250,000 people died. Many more fled north. Only the mediation of U.S. ambassador Dwight Morrow produced an uneasy truce.

By the 1930s and 40s, Mexico cast itself as a nation rooted in tradition yet eager for progress and modernization, a country determined to turn the page on violence. But by the 1950s, the generation born after the Revolution began asking harder questions. Had the upheaval delivered justice, or merely exchanged one form of despair for another? Few gave that uncertainty such haunting expression as Juan Rulfo.

The boy and the myth

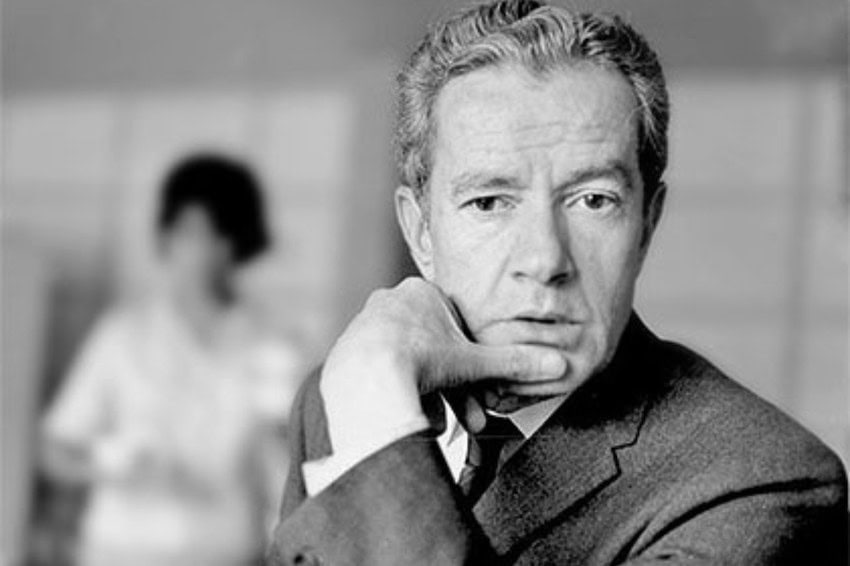

Juan Nepomuceno Carlos Pérez Rulfo Vizcaíno was born on May 16, 1917, in Sayula, Jalisco. He was as artful in shaping his own biography as he was in crafting fiction. In interviews — now archived on YouTube or Spotify — he embroidered his origins into legend.

Later journalists would unpick this embroidery. Both sides of the family were hacendados, with estates such as San Pedro Toxín in Tolimán and the Hacienda of Apulco part of their patrimony. Rulfo often recalled his childhood as marked by the murder of his father, shot, he said, by marauding gangs after the Revolution. His siblings remembered otherwise: their father was killed by the son of Tolimán’s municipal president in an argument over cattle crossing the Rulfo property. Juan was six.

His mother died soon after, undone by grief at seeing her husband’s killer walk free. The children were sent by their grandmother to an orphanage in Guadalajara — an institution Rulfo would later liken to a penitentiary. “The only thing I learned there,” he said, “was how to feel depressed.”

There, in that bleakness, books found him. The parish priest in his hometown had abandoned a small library, and there the boy discovered Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo and even Buffalo Bill.

Becoming a writer

By 1935, he had moved to Mexico City. He likened himself to an orphan drifting alone through an indifferent metropolis. In reality, he lodged with his uncle, Colonel David Pérez Rulfo, a member of President Ávila Camacho’s general staff.

Family connections secured him a desk at the Secretaría de Gobernación. Then he worked as a migration agent chasing foreigners, a tire salesman and an advertising man. At night, he wrote about the ghosts that chased him. His first stories appeared in unlikely outlets — medical journals, engineering bulletins, ephemeral magazines where a voice could grow unnoticed.

The stories

The Plain in Flames introduced 17 stories. Rather than narrating from above, Rulfo let his characters speak, their voices summoning a landscape at once physical and spectral.

He admitted later that he had invented campesino cadences, not merely transcribed them. Among the collection’s most enduring pieces: “¡Diles que no me maten!” (“Tell Them Not to Kill Me!”), often read through the prism of his own family trauma,condemned the Revolution’s pointless violence; “Luvina,” a bleak prelude to the ghostly murmurs of Pedro Páramo; and “No oyes ladrar los perros,” whose stark brutality still stuns readers.

Pilgrims sometimes travel to Jalisco searching for the towns of these stories, only to find they never existed. But their imagined geography has proven more enduring than any map.

Pedro Páramo remains Rulfo’s masterpiece — a novel he warned must be read three times before its meanings reveal themselves. On the surface, it is a ghost story. But its true protagonist is not the landowner Pedro Páramo, whose cruelty ruins a town, but Comala itself.

Comala’s name derives from “comalli,” the griddle for tortillas. Rulfo’s vision was harsher: “a village set on the hot coals of the earth, in the very mouth of hell.” The book was nearly titled “Murmullos” — Murmurs — for the voices that fill it. “Time and space are broken,” Rulfo said, “because the work was done with the dead.”

For some, the novel is an attempt to reassemble his own family history; for others, a reckoning with the Revolution’s aftermath. Still others place him in the lineage of magical realism — alongside García Márquez, Allende, Cortázar — writers who blurred the border between the real and the uncanny and who gave Latin America a new literary authority on the world stage.

Translated into more than 40 languages, Pedro Páramo remains Mexico’s most enigmatic novel. Douglas J. Weatherford’s recent English translation comes closest to capturing its lyric strangeness. Read it in Spanish if you can. If not, find the version that lets you hear its murmurs.

A legacy

Rulfo’s slim library has had an outsize afterlife. His stories are taught in primary schools, adapted into more than 30 films, reshaped into music and theater. One biographer even suggested that his father’s murder was among the most consequential deaths in modern Mexican history. Perhaps an exaggeration, but without that rupture, Rulfo might never have written.

He died 39 years ago. And still his work whispers, like the dead of Comala: murmuring of Mexico’s past, and of the Mexico that endures within it.

If you have never read him, start small — with a single story from The Plain in Flames. Or surrender yourself directly to Pedro Páramo instead, if you’re feeling brave. In scarcely 350 pages, Juan Rulfo created a haunted library that Mexico still carries inside it.

María Meléndez is a Mexico City food blogger and influencer.