“I got in a metro car and I haven’t been able to get out. I’ve been living for more than three or four months here in the underground, in the metro. I’ve passed through Zócalo, Hidalgo, Chabacano a million times. I’ve wanted to go out the door but there’s always someone who pushes me back in. … I eat candy, chocolate, chewing gum and lifesavers. I already have six needle kits, eight box cutters and too many lighters.”

— Translated lyrics of the 1994 song “El Metro” by Mexican band Café Tacuba

“¡Agua de litro y medio a 10! “¡Bolsas de botanas a 5!”

“1.5-liter bottle of water for 10 pesos!” Bags of snacks for 5 pesos!”

These are the kinds of hawkers’ cries that reverberate around the passageways of the Mexico City Metro — a massive public transport system, but also an immense subterranean marketplace where formal and informal vendors and service providers meet the diverse needs of the millions of daily riders.

Amaranth bars, headphones, stuffed toys, jeans, Japanese peanuts, espresso machine coffee, skincare products, McDonald’s soft serve cones, churros, tortas gigantes, tacos, sexual enhancement pills, lingerie, newspapers, books and oh-so-many different kinds of chatarra (junk food).

All these products — and countless others — are available for purchase in the Mexico City Metro system.

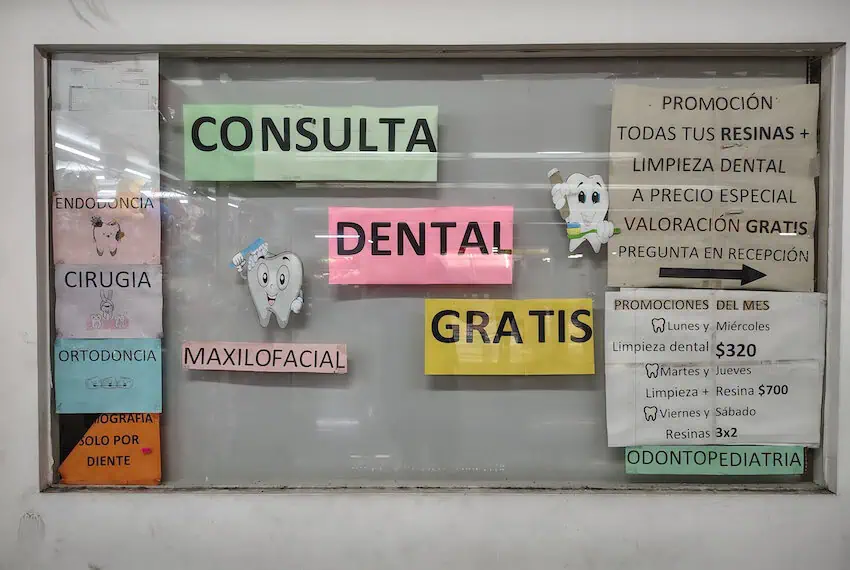

Need a therapeutic massage after a long day at work? You can get one without leaving the Mexico City Metro system. Want to get your teeth professionally cleaned before heading into a big job interview or out on a first date? You can do that in the metro as well. Have a call of nature? You can pay for the privilege of relieving yourself at one of the public restrooms located in various stations, and thus support what is already a very lucrative business.

Even sex workers are known to offer, if not also perform, their services in the metro.

All told, there are around 2,000 “commercial spaces” in the Mexico City Metro — and the renting out of these spaces brings in significant revenue for the Sistema de Transporte Colectivo (SCT), the formal name of the city government-owned metro. There is also a significant number of informal vendors in the metro — in the stations, and on the trains — although their presence has declined in recent years.

Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve ridden the metro on numerous occasions and stopped in at various stations to observe firsthand — and participate in — the commercial activity that takes place on a daily basis in this subterranean precinct of Mexico’s megalopolis. Just as there is an abundance of art and expressions of culture in the metro, so too is there plentiful buying and selling.

The evolution of commerce in the metro

“If you ride the metro more than a few times, the cry of ‘a 10, a 10, a 10, a 10, a 10, a 10, a 10!…10 pesos te vale, 10 pesos te cuesta’ will soon become permanently etched on your brain.”

I wrote those words 11 years ago when thousands of vagoneros — as vendors who sell inside metro cars are known — still roamed the Mexico City Metro system, selling a wide range of products, most commonly for 10 pesos.

Everything mentioned in the Café Tacuba lyrics at the beginning of this article — and much, much more — was available to metro passengers, right in front of them as they criss-crossed this enormous city. A subgroup of vagoneros known as bocineros — because of the large speakers (bocinas) they carried around on their backs to amplify the music on the pirated CDs they were selling — were ubiquitous, and very annoying for some passengers.

“In the country at the moment there’s a lot of unemployment. … I rent and I’ve got two children and I have to find a way to bring money home” one bocinero, Juan Carlos, told Chinese broadcaster CCTV in 2014 as he explained why he was working underground.

Sadly — in my opinion at least — bocineros have since disappeared from the metro (goodbye burned CDs, hello Spotify!), and the number of vagoneros has dwindled, the result of various city crackdowns on informal vendors, including a major one in 2021 and 2022, and the ever present risk of being fined, sentenced to community work, having your merchandise confiscated or even being thrown in jail for up to 24 hours.

Defiant wagon wheeler-dealers, as we might call the vagoneros in English, are still about, still playing the cat-and-mouse game, but the days of one immediately replacing another in a metro car — or even waiting for the other to finish their promotional spiel before proceeding with their own — are over, at least for now.

During a recent day of metro riding — on which, inspired by a TikToker, I planned to buy everything offered to me inside the train cars — I only came away with a mini bottle of Yakult and two Bubu Lubu chocolate bars a woman placed on my knee before coming back to collect my payment.

That is not to say that I didn’t have a fruitful day of subterranean shopping: I bought a range of things at businesses in various stations, including un paste de mole verde con pollo (a green mole chicken pasty), a spiky blue ball for my three-year-old son and a stick of roll-on deodorant (it gets hot and sticky in the bowels of Mexico City).

The soul of commerce in the metro: the vendors

I watched a policewoman walk across the concourse of Metro Garibaldi-Lagunilla to a teenage boy holding a large stack of polystyrene containers. After she made a purchase (and fortunately not an arrest), I wandered over to see what he was selling.

A kind of Mexican-Asian fusion snack pack — an entire meal in fact — was among the youthful peddler’s offerings: a cream cheese-filled chicken milanesa, sushi rolls (one of which had a deep-fried crust), a straggly salad and something else I still haven’t definitively identified.

I decided instead to buy a more economical pack of “sushi” rolls (for 50 pesos), enveloped with cucumber rather than the customary seaweed.

“Can I ask you a few questions?” I ask after I hand over the cash.

“I’m in a hurry,” he replies. “I’ve got to keep moving.”

I pace through the station alongside the adolescent, whom I soon learn is 15 years old and named Ángel.

“I saw a policewoman buy a meal from you,” I mention.

“Other police officers take all my meals and kick me out of the station,” Ángel responds, and in doing so explains why he has to move swiftly to deliver his meals to his clientes.

Among those customers are vendors who spend their entire workdays underground and savor a hot (or at least lukewarm) meal brought in from the outside world.

“¿Tienes mariscos hoy?” (Do you have seafood today?) one frequent customer enquires as we walk. “I’ll bring it to you ahorita,” Ángel responds.

Ángel tells me he’s still in school but earns good money when he comes underground to sell the meals he picks up from an outside fonda (diner), a job he has been doing since the tender age of 12.

The adolescent ambulante (roving vendor) is one of several metro merchants I spoke to for this story.

At Metro Chabacano, I met Ana, a young woman in charge of a kiosk where books are sold just inside the turnstiles at one of the station entrances.

Also in Chabacano — a busy station where three different lines converge — I spoke to Rolando, an employee of one of the metro’s many tiendas naturistas, where products such as chili and garlic shampoo, shark cartilage capsules and “Praw Praw Sex” pills are on sale.

“Why are there so many ‘natural products’ stores in the metro?” I ask Rolando, who has worked at the same tienda in Metro Chabacano for 22 years.

Two reasons, he says: A lot of people use the metro every day, meaning there is plenty of passing trade, and, secondly, many Mexicans have a lot of trust in traditional medicinal products, which have a rich history in Mexico.

Rolando tells me that his best sellers are natural products used to treat diabetes, which afflicts millions of Mexicans. Like any good salesman, he says he has full confidence in the natural remedies he stocks.

Ana, an employee of the Chabacano book stand for the past few years, tells me she sells 15 to 20 books a day. She highlights that the business is “on the way” for commuters, making it convenient for them to pick up something to read, or buy a gift, as they head for the platform to catch a train, or to their homes at the end of the day.

Ana notes that sales declined during the pandemic, when fewer people were using the metro and more people were working from home, and also acknowledges that commuters are more commonly glued to their cell phones than buried in books these days.

Indeed, whether a book vendor is located above ground or below, the challenges they face in the 21st century are the same. Still, book stores and stands in the metro are survivors, even as book sales decline. There is even a bookstore-filled tunnel linking the Pino Suárez and Zócalo stations in the historic center of Mexico City. Called “Un paseo por los libros” (A stroll through books), the literary underpass will celebrate its 30th anniversary in 2027.

Many other metro businesses fail to even get close to that kind of longevity. As is the case above ground, in the bustling streets of this city or any other, commerce in the metro is in a near constant state of flux. New businesses open up, old ones close down, your favorite vagonero is there one day, the next day he is gone.

A commercial hub, inside and out

With millions of passengers entering and exiting the Mexico City Metro’s 163 stations on a daily basis, it can make good business sense to set up a commercial enterprise at or near the entrances to the capital’s subway system.

Proximate to the portals to the underground, these outdoor spaces are the domain of taco stands serving hungry people in a hurry, of shoeshiners who can make your black brogues glisten, and of countless other businesses.

Step outside Metro Allende in the capital’s historic center and you’ll be mobbed by touts drumming up business for nearby eyewear stores. Some stations merge into makeshift marketplaces — mazes of merchandise and antojitos (tacos, quesadillas and the like) sizzling on griddles.

Outside Metro La Villa-Basílica, located in the city’s north near the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, sidewalk commerce is dominated by vendors of religious artifacts who sell to the millions of people who flock to the world’s most visited Catholic pilgrimage site every year.

It was here that I met Miguel Gutiérrez, a vendor of candles in glass holders emblazoned with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

“I sell 60 candles on a good day,” says Miguel, who laments that business is often much, much slower.

Still, like the many other formal and informal vendors inside and outside the metro, who collectively make the transit system a much more interesting, colorful and louder place, he will get up tomorrow, and the next day, and return to his little patch of Mexico City to try his luck again.

After all, as the biblical aphorism goes, “He who does not work, neither shall he eat.”

By Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies (peter.davies@mexiconewsdaily.com)