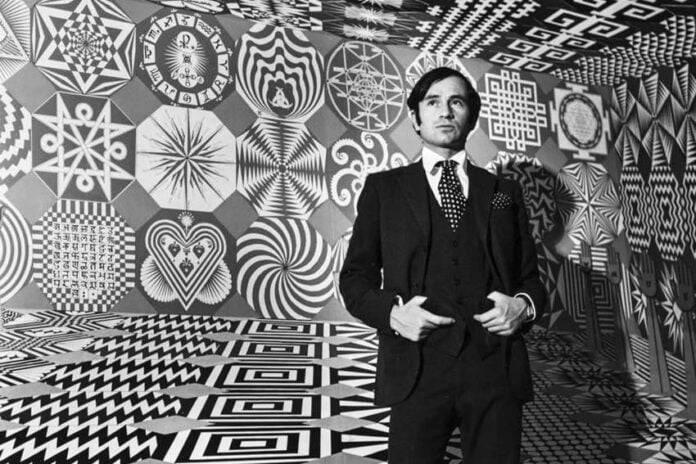

You may not have heard of Mexican artist Pedro Friedeberg: The 89-year-old artist has kept a relatively low profile compared to many of his art-world colleagues over the last several decades.

Yet Friedeberg’s work is held in the permanent collections of over 50 museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Musée du Louvre, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. He has participated in over 100 exhibitions and continues to collaborate with brands like Montblanc, Jose Cuervo and Corona.

Despite this institutional recognition and commercial success, however, he remains relatively “under-the-radar” compared to his contemporaries who garnered more fame, like Salvador Dalí. But this distinction seems to suit him just fine.

Friedeberg’s biography: European roots

Born in Florence in 1936 to Jewish parents fleeing Mussolini and escaping the Holocaust, Friedeberg arrived in Mexico City as a 3-year-old. His grandmother, who had settled in Mexico years earlier in 1911, introduced him to art books, featuring works such as Arnold Böcklin’s “The Isle of the Dead.”

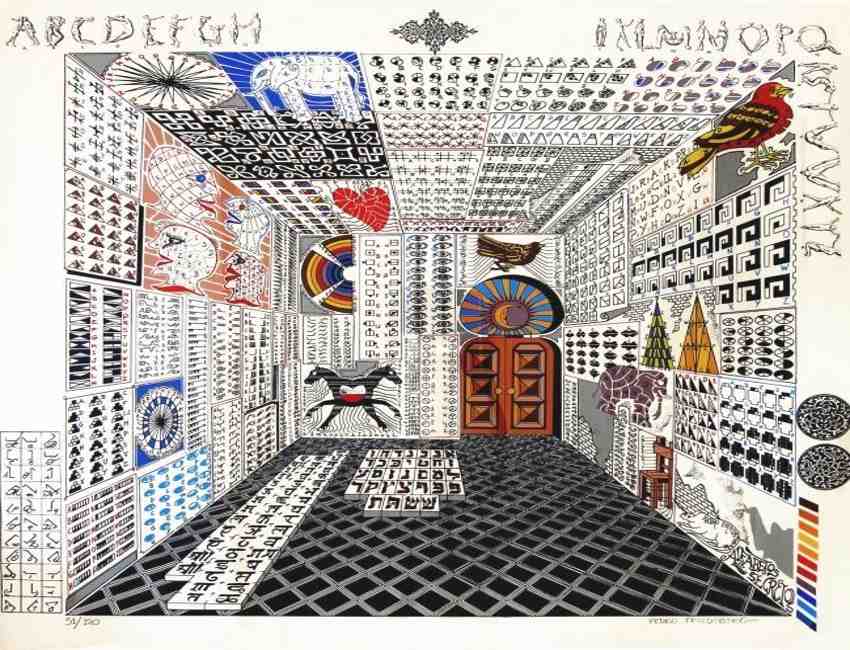

These early influences — including Renaissance architecture, Gothic forms and, later, the Aztec codices he discovered in his adopted homeland — would create the visual vocabulary and symbology that permeate his work.

In 1957, Friedeberg enrolled in architecture school at Universidad Iberoamericana but resisted his professors’ insistence on strict symmetry and conventional forms; instead, he leaned toward his imaginative impulses.

He began drawing fantastical, impossible architectural designs: houses with artichoke roofs, and buildings that appeared to twist and fold in on themselves. These sketches caught the attention of Mathias Goeritz, a renowned painter and sculptor who encouraged Friedeberg to leave his architectural studies to pursue art.

Through family connections, he met surrealist artists like Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, becoming part of Los Hartos (The Fed-Up Ones), an irreverent collective that rejected the political and social realism dominant in postwar Mexican art, in favor of art for art’s sake.

The romantic tumult of his personal life — four marriages, including one to Polish countess Wanda Zamoyska that he described as surreal, as a circus and as crazy, but tiring — eventually melted into a quieter domestic rhythm.

With his last wife, Carmen Gutiérrez, whom he described as “a very serious woman,” he raised two children. Fatherhood changed him, curtailing the nights of drinking and worldwide travel that had characterized his earlier years.

Practical yet absurd

Friedeberg is most famous for his work “Hand Chair” of 1962. The piece is both furniture and sculpture, practical and absurd: a giant wooden hand inviting you to sit in its palm, using the fingers as backrest and armrests.

The chair exemplifies Friedeberg’s philosophy of useless beauty, transforming a functional object into something delightfully impractical. Today, giant Hand Chairs sit atop prominent buildings in Mexico City, while authorized and unauthorized reproductions are carried in design showrooms and flea markets around the world.

But to focus only on “Hand Chair” would be to miss the breadth of Friedeberg’s prolific practice. His work spans a wide variety of ideas and influences: paintings filled with optical illusions and hybrid symbols, intricate prints drawing on everything from the Torah to Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, furniture that appears to sprout human appendages, psychedelic album covers and montages where impossible architecture incorporates symbols from Catholicism, Hinduism and the occult.

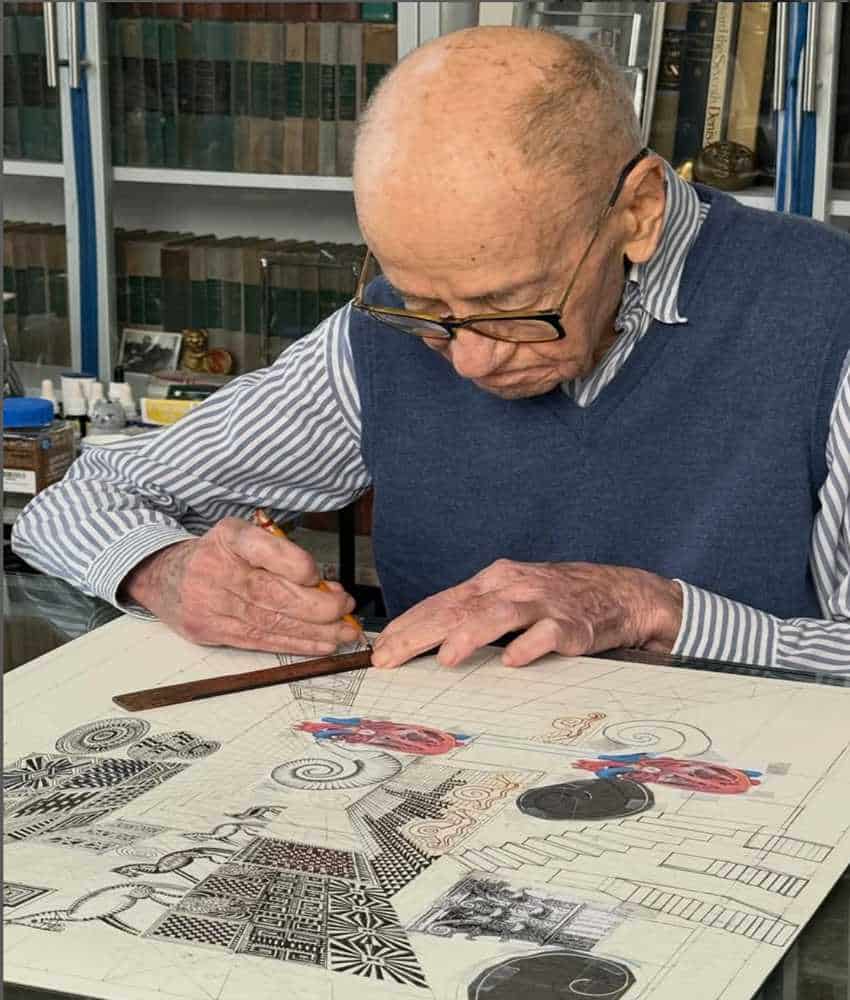

Each piece is produced with detailed technical precision. Friedeberg works entirely with traditional media, using rulers, pencils, erasers and protractors, like the craftsmen of another time.

“I admire everything that is useless, frivolous and whimsical,” Friedeberg once said, and this philosophy extends to his opinions on contemporary art. He hates minimalism with a passion, calling it “a hoax,” and insists that art should not be reduced to the abstract.

This stance put him at odds with figures like Luis Barragán, whose colorful, simple modernist architecture Friedeberg has openly disdained.

Friedeberg wouldn’t call himself a surrealist, per se. It’s a typical response from an artist who has spent his career humbly resisting categorization, even as the label “the last living Surrealist” follows him. But perhaps the resistance to classification makes sense: Friedeberg’s work — with its geometric precision, architectural impossibilities and almost psychedelic imagery — feels like the meticulous constructions of a trained architect who simply refuses to acknowledge the laws of physics.

What makes Friedeberg so fascinating is this contradiction: He’s an artist of incredible technical skill who dismisses meaning and symbolism in his own work, a surrealist who rejects the label, a creator of impossible architectures who never completed his architecture degree, a maker of useful objects designed to be useless.

In an art world often dominated by conceptual gestures and theoretical abstractions, Friedeberg offers something increasingly rare: pure craft in service of pure whimsy, meticulously rendered worlds where nothing makes sense — and that’s the point.

A 2022 Netflix documentary simply titled “Pedro,” tells the tale of how filmmaker Liora Spilk Bialostozky spent a decade documenting the artist’s life, capturing both his public persona and the more tender, private self. The film offers an intimate portrait of a man who describes his work as “a commentary on other people’s art,” even as his technical genius and originality remain undisputed.

It’s worth watching for anyone interested in one of the last true intellectuals of our time, an artist who consults the I-Ching daily and maintains a collection of saints despite identifying as an atheist, who creates art that references centuries of visual culture while remaining stubbornly, unmistakably his own.

Still building impossible worlds

At 89, Friedeberg shows no signs of slowing down, still granting interviews and maintaining his rigorous studio practice, while his work continues to be displayed in new gallery showings. Friedeberg lives in the same Colonia Roma home where he works in Mexico City, a maximalist sanctuary he once jokingly called “un museo de basura” (a museum of garbage) filled with art by Man Ray, José Luis Cuevas and Rufino Tamayo alongside his own creations and collected curiosities.

It seems Friedeberg will keep doing what he’s always done: creating his fantastical worlds, one impossible structure, one absurd hybrid creature, one useless beautiful object at a time. For an artist who insists that art is dead and nothing new is being produced, he seems committed to proving himself wrong.

Monica Belot is a writer, researcher, strategist and adjunct professor at Parsons School of Design in New York City, where she teaches in the Strategic Design & Management Program. Splitting her time between NYC and Mexico City, where she resides with her naughty silver labrador puppy Atlas, Monica writes about topics spanning everything from the human experience to travel and design research. Follow her varied scribbles on Medium at medium.com/@monicabelot.