Oaxaca’s intricate weave of color, culture, cuisine, and creativity attracts Mexican folk art collectors and cultural travelers from far-flung corners of the globe. From Nelson Rockefeller, who fortified his extensive collection with hand-crafted artisan pieces while traveling through Oaxaca in the 1960s, to Janice Hatfield, who dedicated a significant portion of her amassed collection to the Smithsonian Institute, Mexico’s most colorful state stands as a leader in artistic innovation.

Who can we thank for putting Oaxaca on the creative community map? The 10 artists below represent just a fraction of the region’s visionary prowess, each contributing to the development of Oaxacan expression in a powerful way.

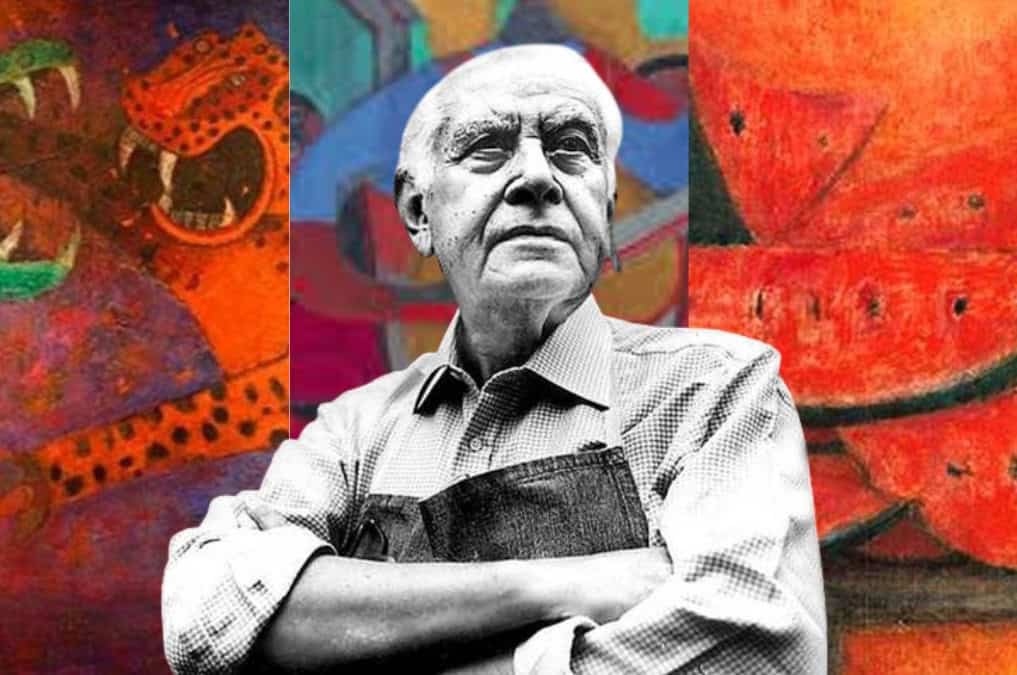

Rufino Tamayo (August 26, 1899 – June 24, 1991)

Painter, modernist visionary

Rufino Tamayo was orphaned by age 12. Born in Oaxaca, his father abandoned the family and his mother died of tuberculosis. He moved to Mexico City to live with an aunt, helping run her family’s fruit stall. This experience would profoundly impact his artistic journey, inspiring the legendary watermelon motifs for which he is so well known. Fiercely independent, Tamayo rebelled against the art scene which, at that time, was largely a series of political statements by the likes of Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Instead, Tamayo chose to focus on a unique blend of European modernism and Mexican roots. He would eventually found two museums: Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, and Museo de Arte Prehispánico de México Rufino Tamayo in Oaxaca.

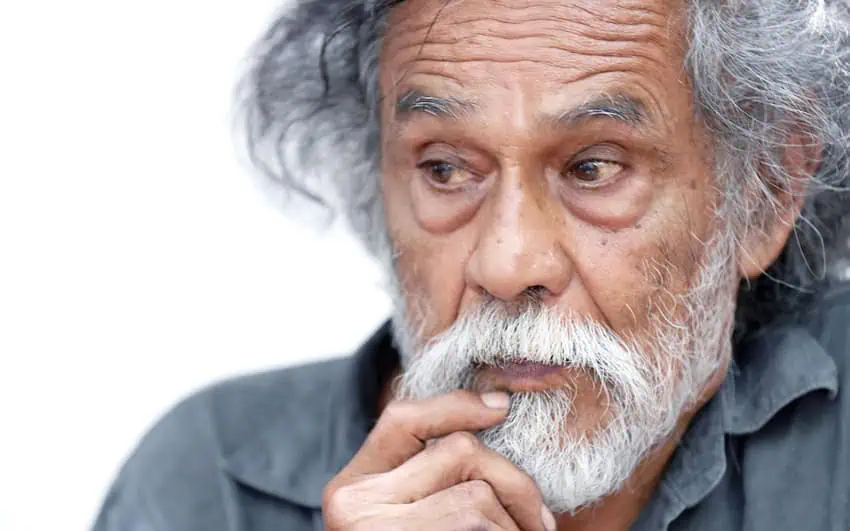

Francisco Toledo (July 17, 1940 – September 5, 2019)

Painter, sculptor, cultural activist

Oaxaca’s landscape and culture laid the groundwork for Toledo’s surrealist, at times fantastical, paintings, known for their rough lines and rich textures. Thanks to a rural upbringing in a Zapotec family, he was immersed in legend, myth, and the region’s wild nature from a young age. After his parents sent him to high school in Oaxaca City in the hopes he would become a lawyer, Toledo went on to study art, spending time in Mexico City, New York, and Paris, where he would befriend Rufino Tamayo. A tireless advocate for Oaxacan heritage and social justice, Toledo founded the beloved Instituto de Artes Gráficas de Oaxaca (IAGO). Perhaps his most famous work came in the form of activism — in 2002, the artist organized a protest against a proposed McDonald’s in Oaxaca City, handing out tamales at the potential site and generating the slogan “Tamales sí, hamburguesas no.”

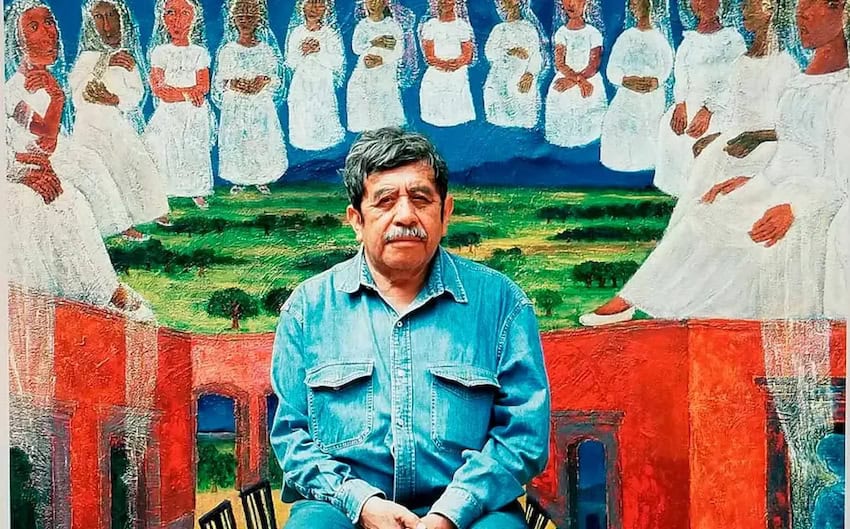

Rodolfo Morales (May 8, 1925 – January 30, 2001)

Painter, surrealist, restorer

Morales grew up in a small Oaxacan village in a working-class family. A solitary child, he often turned to drawing to pass the time. While his parents recognized early on that Morales had artistic talent, it was his Aunt Petra who fostered his imagination and encouraged his creative side. Though his education was interrupted, Morales would later attend the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City to study art. His style, magical realism centered on the resilience of Oaxacan women and the matriarchy, can be found on canvas and the walls of important buildings, notably the Municipal Palace of Ocotlán, which showcases a colorful depiction of local village life. Morales dedicated his latter years to restoration, bringing back to life Oaxaca’s most historic churches and convents, including the 16th-century Convent of Santo Domingo.

Amador Montes (June 16, 1975 – )

Painter, curator, boutique hotel creator

Amador Montes is one of Oaxaca’s most celebrated contemporary artists. He’s presented his paintings locally and globally, each piece inspired by dreams, memories, and emotions, evoking feelings of nostalgia. His luminous color palette—which reflects the full spectrum of hues ranging from bold to neutral—often features black lettering, notably the name Carmen. Much of his work is dedicated to his mother, and her name graces everything from Montes’ paintings to the two boutique hotels he opened in Oaxaca City, both named Casa Carmen. Beyond creating, Montes is also a curator, passionate in his support of young Oaxacan artists and known for hosting local exhibitions and creative dialogue.

Manuel Jiménez Ramírez (June 9, 1919 – March 4, 2005)

Alebrije pioneer and healer

Manuel Jiménez Ramírez is credited as the originator of the Oaxacan alebrije, the state’s vibrant tradition of fantastical, hand-carved wooden animals and mythical creatures. As a child, he began by molding animals in clay, later discovering his true passion was in woodcarving. Known locally as “el divino,” Jiménez Ramírez believed himself to be the reincarnation of an artist, and his neighbors often regarded him as a spiritual healer. Beyond art, he worked as everything from a cane cutter to a bricklayer, basket maker, and community leader during Holy Week celebrations. Today, his children and grandchildren carry on the family legacy, shaping the artistic identity of Oaxaca at large.

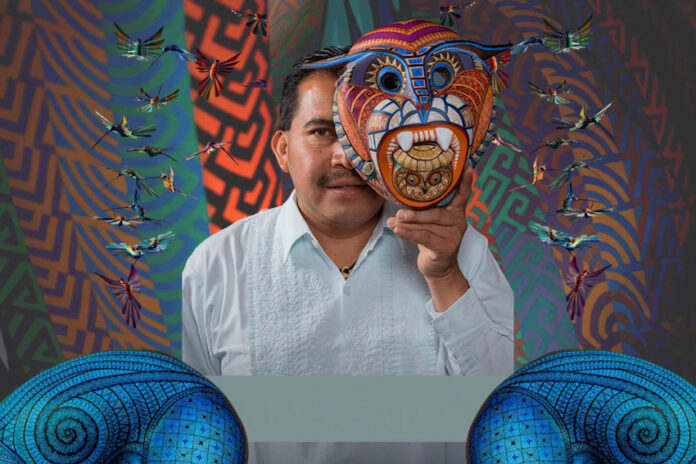

Jacobo Ángeles (March 14, 1973 – )

Master alebrije carver and Zapotec cultural advocate

Jacobo Ángeles’ creative spirit was nurtured by growing up in a Zapotec household surrounded by woodcarvers and artisans. After the sudden loss of his father when he was just 12, the young creator took charge of the family workshop, teaching the craft of carving to his younger siblings and supporting the household.

He later married María del Carmen Mendoza, and together they built the Taller Jacobo y María Ángeles, a cultural hub where traditional Zapotec weaving and carving techniques blend with cutting-edge design. His alebrijes are notable for their intricate patterns — inspired by Zapotec symbols and ancient mythology — and frequently combine mythical creatures with human features. In 2014, Jacobo was invited to meet Pope Francis and exhibit 1,200 hand-carved nativity scene figures and Christmas ornaments at the Vatican Museums.

Josefina Aguilar (February 22, 1945 – )

Iconic potter and figurine artist

Hailing from the same town as Rodolfo Morales, Josefina Aguilar is internationally lauded for her vibrant, molded clay figurines representing Mexican rural life, festive traditions, saints, historical figures, and community rituals. Taught by her mother and grandmother from the age of six, Josefina began gaining attention in her youth, and her works would eventually be collected by connoisseurs like Nelson Rockefeller. Despite losing her sight in 2014, Josefina continues to shape her whimsical muñecas (dolls), relying on touch while her children help her paint. Her home and studio are a beacon for folk art collectors, and her family remains a central force in the evolution and global adoration of Oaxacan ceramics.

Pastora Gutiérrez Reyes (dates not publicly confirmed)

Revolutionary weaver and women’s advocate

BMW Foundation

Pastora Gutiérrez Reyes is a Zapotec leader and weaving artist from Teotitlán del Valle. In 1997, driven by the lack of opportunities for women in her traditional community, she cofounded Vida Nueva, the village’s first all-women’s weaving cooperative.

Together with her mother, grandmother, and friends, she guided the co-op to economic independence, education, and social change. Through Vida Nueva, Pastora helped bring public health education, workshops on domestic violence and support to further educate local women. Her impact is as much about advocacy as artistry: Today, the cooperative’s Mexican textiles are recognized for blending Zapotec tradition with the group’s innovative designs, and the co-op empowers women in rural Oaxaca.

Doña Rosa (September 4, 1900 – July 12, 1980)

Legendary innovator of Barro Negro

In the 1950s, Doña Rosa — born Rosa Real Mateo de Nieto in San Bartolo Coyotepec — dramatically transformed the fate of Mexican pottery with a single discovery. Traditionally, the region’s barro negro (black clay) was matte and gray, relied on for its broad utility rather than its aesthetic. Doña Rosa found that by burnishing the clay with a quartz stone and firing it at a lower temperature, she could create a deep, lustrous black sheen.

This technique made Oaxacan pottery famous throughout the world. Doña Rosa’s descendants continue to run the family workshop to this day, and for art collectors serious about Mexican folk art, it’s a must-visit. Doña Rosa’s ingenuity not only upended an entire craft it also inspired a wave of creative and economic activity that continues to reverberate in Oaxaca’s Central Valleys.

Enedina Vásquez Cruz (1963 – )

Contemporary terracotta sculptor

Enedina Vásquez Cruz carries the centuries-old tradition of Oaxacan ceramics forward with her award-winning terracotta figures and jewelry. Trained in her family’s workshop from a young age, Enedina innovated the art when she recovered ancient slip recipes revealing a method to create an earthy palette.

In fact, the recipes uncovered over 80 natural colors, all derived from traditional sources. Her detailed works are generally centered on Indigenous women in regional dress, as well as double-sided pieces depicting religious icons and historic narratives. Her ability to connect Oaxaca’s pre-Hispanic past to contemporary beliefs has garnered Cruz a number of major national prizes, making her a major force in the region’s artistic landscape.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog or follow her on Instagram.