The 16th and 17th centuries were troubling times in Mexico. With the Spanish conquest came Catholic doctrine, which conflicted with Indigenous religious beliefs and rituals.

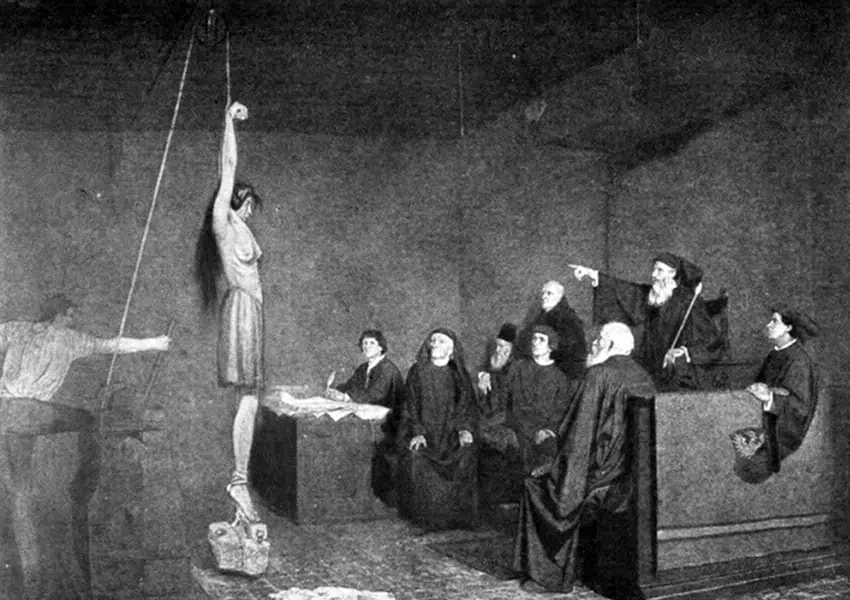

Spanish attempts to convert Mexicans to Catholicism weren’t going well, so the Holy Inquisition stepped in to speed up the process.

People feared the Inquisition with good reason: witchcraft, sorcery and adultery were accusations made under the umbrella of heresy, and those found guilty by the Catholic court could be burned alive at the stake.

Neighbors accused neighbors; family members accused other family members; everyone feared being turned in to the Inquisition if they didn’t turn in someone else. Women who were herbalists or curanderas (healers), or who were powerful in the community, were often prime targets.

So go the legends of La Maltos and La Mulata of Córdoba, two women who were said to have been accused and sentenced to death for witchcraft but escaped — using witchcraft, of course.

The legend of La Maltos, the Witch of the Arches of Ipiña, takes place in San Luis Potosí in the 17th century. At the time, much of the population had a high socioeconomic status, and La Maltos was a very powerful figure within her class. It was said that her name was María Ignácia de Malto and that she was so influential, she had a position with the Holy Inquisition.

As the story goes, La Maltos rented a large building from a powerful family in San Luis Potosí in the middle of the city and used the ground floor for torture and executions on behalf of the Inquisition, while she lived in the upper part of the building. There, she was said to have cast evil spells to end her enemies’ lives — 30 of them men with important government positions. Some were men she targeted for revenge, including former lovers who rejected her.

At night, she would ride wildly through the city streets (with impunity due to her position) in a grand carriage drawn by two large horses as black as night.

However, she made a mistake: she murdered two men from families more powerful than her.

Once accused, it is said that La Maltos made no effort to defend herself and was sentenced to death for murder and witchcraft. Before her execution, she made one final request: that she be allowed to paint a mural on the wall of her home, called the Arches of Ipiña.

Her request granted, she was taken to the house and given paints and brushes. On the wall, she painted a lifelike picture of herself mounted on her carriage. To the astonishment of the police chief, mayor, and other onlookers, the painting supposedly came to life. La Maltos mounted the carriage and disappeared through the wall, never to be seen again.

The building once known as Arches of Ipiña still stands in the San Luis Potosí’s historic district with the mural intact. Some say the ghostly carriage can be seen emerging from the walls and that at night, you can hear the chanting of spells from inside the house.

Another legend, that of La Mulata of Córdoba, took place in the 16th century. The records of her trial by the Holy Inquisition can be found in Mexico’s National Archives. Known as Soledad, she was a skilled herbalist from the city of Córdoba, Veracruz. She was beloved by the people she helped and known for her striking beauty.

The townspeople of Córdoba came to her for solutions to their problems and always left satisfied. A young woman without suitors; a worker without work; a lawyer without clients – they all came to her for help — telling others that Soledad had solved their problems.

Although loved by many, Soledad was also resented by women and men alike. Envious women speculated that she was a sorceress that made a pact with the devil to remain so young and beautiful year after year. Yet she showed no interest in suitors, causing many men to resent her indifference.

This legend has had many different versions retold over the years. Some say she was the lover of wealthy landowner Don Luís de la Cueva, who died mysteriously in his home; the authorities suspected Soledad but did not have enough evidence to incriminate her. Others say she was turned into the Inquisition by a jealous wife whose husband commented once too often on her captivating beauty.

Perhaps the most popular is that Soledad was turned into the Inquisition by the Mayor of Córdoba, Don Martín de Ocaña, in anger over her rejection of his amorous advances. Legend has it that he started the rumor that she was a witch, and that she had given him a potion that made him fall in love with her.

The townspeople, scared of being judged by the Holy Inquisition, corroborated his story. Upon being questioned, many witnesses said they saw her fly over rooftops at night while laughing ghoulishly. They also claimed that Soledad forced them to sell love potions.

Regardless of who made the original accusation, La Mulata was locked up in the San Juan de Ulúa prison and sentenced to death at the stake for practicing witchcraft. Just before her execution, however, she asked the guard if he could bring her a piece of charcoal so that she might draw some pictures on the wall. The guard admonished her for not praying for forgiveness in her final hours, but, perhaps due to her beauty, obliged her request.

The guard watched in amazement as Soledad drew in great detail a sailing ship on the ocean. She then asked him, “What is missing from this picture?”

Looking at it, he said, “Nothing that I can see. It’s perfect. Except, it needs someone to navigate it.”

Laughing, Soledad replied, “You’re right!” She jumped aboard the ship and sailed off — right through the wall of her prison.

People still report sightings of La Mulata in Córdoba. They’ve reportedly seen her flying overhead — her dark eyes gleaming like the devil’s — and laughing maniacally. Others have reported strange chanting and lights shining from her house. At times, people have seen a ghostly ship coming out of the walls of the prison with Soledad on board.

Even former president Porfirio Díaz (1848–1876) recounted seeing her apparition and watching as she turned into an owl and flew away.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.