Mexico City residents often forget that they live nearly on the doorstep of one of the world’s most dangerous volcanoes. The city’s infamous smog rarely allows even a glimpse.

But Popocatépetl has dominated the geography, history and culture of the region. It remains iconic for Mexico, and its recent activity makes experts and the government nervous.

Popocatépetl is both exceedingly majestic and dangerous, which influences how humans relate to it. Its name comes from Nahuatl and means “smoking mountain.”

For Mesoamericans, it was the source of both fire and water, as rain clouds gather there. The Florentine Codex notes that even decades after the imposition of Catholicism on the native peoples in the area, pilgrimages to both petition and appease the volcano continued.

Today, the volcano is often called simply “(El) Popo” and “Don Goyo.” The first is a shortening of the difficult Nahuatl, but the second has a story.

“Goyo,” a nickname for Gregorio, is probably from an early colonial renaming of the mountain. But according to legend, it comes from the appearance of an old man near the town of Santiago Xalitzintla, Puebla, who introduced himself as Gregorio Chino Popocatépetl and is believed to be the spirit of the mountain.

Either way, the volcano continues to receive offerings and pilgrimages today, just now in the guise of Saint Gregory’s feast day.

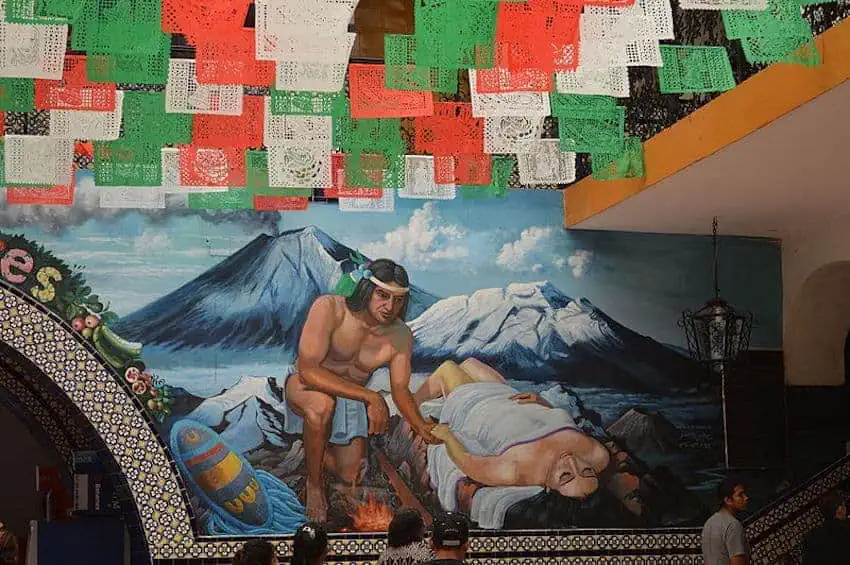

Popocatépetl appears in numerous artworks from the region, and is featured in the English-language novel “Under the Volcano” (1947) by Malcolm Lawry. If you have seen the image of an Aztec warrior carrying a limp maiden, it is a reference to a “Romeo and Juliet”-like story that explains why Popo is active and its “partner” volcano, Iztaccihuatl, is not.

Most modern humans generally dismiss the supernatural, but I’ll mention here that Popocatépetl’s crater is the focus of stories of UFOs that may have a base within, despite the heat.

Don Goyo may no longer command worship — but it still should be respected. With over 46 active ones, Mexico is no stranger to volcanoes, but none have such a population density living so nearby.

Popocatépetl is an active stratovolcano — like Hawaii’s Mauna Loa and Indonesia’s Krakatoa — and it’s the second tallest active volcano in North America (5,425 meters). It and Iztaccihuatl separate the Valleys of Mexico and Puebla.

Popocatépetl arose over 730,000 years ago, according to scientists. Humans arrived only 10,000 years ago, and since then, archeological finds and written records evidence the volcano’s impact on them (us).

An eruption is believed to have spurred migrations that resulted in Teotihuacán. Eruptions have been recorded as early as the 1300s.

Hernán Cortés was impressed by the two volcanoes, describing them as “…two marvelously high mountains whose summits at the end of August are still covered with snow so that nothing else can be seen of them. From the higher of the two, both by day and night, a great volume of smoke often comes forth…”

Since the fall of Tenochtitlán, Popocatépetl has had 15 significant eruptions, but none (yet) have had major destructive consequences. One reason is that its last plinian eruption (i.e. extremely explosive — think Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79) occurred in A.D. 800, when the valleys did not have the population density they have now.

The area around the Popocatépetl and Iztaccihuatl volcanoes is the Izta-Popo National Park, but unlike parks in the United States and Canada, visitation is extremely limited.

After 70 years of inactivity, Popocatépetl came back to life. First, its glaciers began to melt, but it was the December 21, 1994, eruption that got everyone’s attention.

Since then, a column of smoke from El Popo has been visible on most days, along with ejections of steam, ash and rock.

There is always the risk of a major eruption, says Dr. Hugo Delgado Granados of the Geophysics Institute of UNAM. Such an eruption could obliterate everything within 15 km and cause serious damage as far as 100 km away — a radius that’s home to about 25 million. And urbanization is creeping up the slopes as Mexico City and Puebla continue to grow.

Ash is the main issue for the region. Right now, there is a 12-km exclusion zone around the crater because of fallout. Light ash has fallen much further away, either toward Puebla or Mexico City, depending on seasonal wind patterns.

Popocatépetl has caused some headaches for airlines, but more ash accumulation could snarl land traffic as well — and if rain is involved, the resulting sludge would clog drainage systems.

Lava from Popocatépetl’s crater is not a major threat. There is plenty of magma under the valleys, but their danger comes from small “pop-up” volcanoes (like Paricutín in Western Michoacán), that are extremely hard to predict.

Volcanoes like Popocatépetl can give some warning of an upcoming eruption, which is why monitoring, warning systems and evacuation plans are essential to prevent tragedies.

Mexico’s main warning system is a stoplight-like advisory system called the semáforo de alerta volcánica, which currently is in yellow (caution) — Phase 2. Since 1994, the general advisory has been as high as yellow-3 (the status just before red), with the 12 km exclusion zone in red.

Today, it is possible to see what Popocatépetl is up to 24/7. Popocatépetl’s crater is a favorite of Webcams de México, where you can look at it anytime and receive alerts in social media when something interesting happens.

Although evacuation routes are well-marked, a major evacuation would be challenging at best, both because of the number of people and due to the fact that the Valley of Mexico is crowded, with few ways out.

Could Mexico evacuate everyone in time in the worst-case scenario?

Delgado Granados says that there are many factors to consider but also that monitoring systems and evacuation plans are being constantly upgraded. He also points out that in 1994, Mexico was able to evacuate 70,000 people in less than three days, despite being caught relatively by surprise.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.