Read a summary of Mexican history, and it might seem that very little happened between the first humans wandering across the ice-frozen sea to reach the Americas and the Olmecs carving their great stone heads. Yet 93% of the story of human occupation of Mexico lies between these two events!

Little evidence survives from this long period, so it remains poorly understood. Even the question of when humans arrived on the continent cannot be answered with any certainty. For a long time, the vision was of small family groups following herds of wild animals across a frozen landscape, surviving in a cold, harsh world, thanks to a technology that was largely limited to fire and a few stone tools. For much of the last century, history books confidently dated this event to around 12,000 years ago.

Rewriting the early history of Mexico

However, few historians still believe that date is accurate, or that the story is so simple.

The argument is now edging towards two, three or even several waves of migration, the earliest of which might have occurred around 30,000 years ago. There is also an acceptance — almost an expectation — that future archaeological discoveries will push that date back further and reveal the story to be even more complex.

Dating when the first humans arrived in America also determines how they got here. Between 29,000 to 19,000 years ago, glaciers reached their maximum expansion, covering much of North America. If humans arrived during this time, then the vision of them following herds southwards seems unlikely. Instead, we have to imagine the pioneers working their way down the coast in small boats or rafts.

Whenever they came, or however they traveled, humans arrived in very small numbers, and evidence of their passage — such as stone tools lost or cast aside or the remnants of campfires in the mouth of caves — has proved elusive to find and difficult to date. With our knowledge resting on such little evidence, each new find has tended to challenge, rather than support, the standard version of the story.

Stone tools in the Chiquihuite cave

As recently as 2012, the discovery of thousands of stone tools at the Chiquihuite cave in Zacatecas state suggests that the date for human arrival in Mexico should be pushed back as far as 26,500 years ago. This would, in turn, make us reconsider the date of the first human arrival in the Americas, supporting the possibility that this occurred before the glaciers gripped the north of the continent.

It must be pointed out that, as exciting as the finds at Chiquihuite cave have been, they have been disputed. It has been questioned, for example, whether the stones are really man-made tools or formed naturally. And why does a site that would have been visited for 10,000 years show no sign of human fires?

Nevertheless, while the evidence is still thin, archaeological digs, such as the one continuing to take place at Chiquihuite, do give us some idea of how people lived during this long, little-understood period.

The oldest sites in Mexico

Evidence for the first human arrivals in what is now modern Mexico has been identified from the Baja California peninsula, where there were large lakes at the time, to Costa Rica. When small groups broke away from the bigger family, they might have to wander some distance to find an environment that would support them. As a result, humans spread quickly, but sparsely, across the continent. So, while these oldest sites can be found all across Mexico, we have only identified a dozen or so such locations from this early period, and each site (except for the Chiquihuite cave) has only given up a very few artifacts. What we have are a few animal bones, hearths where fires had been lit and, most numerous of all, stone tools.

The tools from this early age were created very simply by banging one stone against another to produce a sharp edge. The result was a large, handheld tool that could do several jobs, including cutting, squashing, scraping and stabbing. However, they were not crafted to do any of these tasks particularly well. Most notably, there were no small, sharp projectiles that could have been used for hunting. These might have existed in bone, wood or even ivory, but if so, none have survived.

The advance in technology that took place around 14,000 years ago was so sudden that it has been argued it marks the arrival of a new wave of humans into Mexico. It coincided with a climate that had become more forgiving, with large animals now roaming across the land in greater numbers.

Did early humans in Mexico hunt megafauna?

In 2019, as workmen cleared the site for the new Felipe Ángeles International Airport, they started to find giant bones. This had once been an area of swamp where prehistoric animals lived, fed and died. By 2022, 500 mammoth bones, 200 camel bones and evidence of other animals — such as wild horses and giant sloths — had been excavated. As a result, we have a detailed insight into the environment that the people of this age would have hunted in.

While we imagine mammoths as large, fur-covered creatures, well-adapted to the cold, they in fact consisted of many different species, and the Columbian mammoth, which is believed to be the species found in Mexico, wandered as far south as Costa Rica. DNA does not survive well in the tropics, but with so many bones now discovered at the airport, a few samples could be extracted. The results suggest that these animals should be reclassified as a separate Mexican mammoth.

These wonderful creatures survived as an isolated population, even while their northern cousins were dying off. One explanation for this is that they were more varied eaters, not dependent solely on grass but also grazing on scrub and trees. Did humans hunt such powerful animals, and did human hunting contribute to their eventual extinction in Mexico?

Weapons for the hunt

Many years before the discoveries at the airport, a site at Santa Isabel Ixtapan, a town in México state, revealed the remains of two mammoths that appear to have been chased into the swamps, where human hunters may have hassled them until they collapsed. However, some archeologists question how often such hunts could have been successful. To paraphrase archeologist Richard MacNeish, if a man killed a mammoth, he probably never stopped talking about it for the rest of his life.

To even occasionally hunt such large animals would have required a cooperative group effort, probably with some system of hierarchy. It helped that stone tools had become far better crafted, new techniques producing projectiles that might be fixed to a wooden shaft to create a formidable spear. By this time, the stone industry had become so varied in its production that we can even identify regional differences. One type of fluted projectile, for example, is only found in the highlands. There is also evidence of the use of organic material, suggesting these people might have had ropes, nets, bags and baskets.

Whether big animals were a regular part of the diet or a rare bonus, man was successfully adapting to this new world. Genetic research argues for a notable increase in population at the beginning of this period. There are certainly far more sites identified in the archaeological record from this point onwards, with some 40 scattered across Mexico. However, we should not be too fixated on modern borders. The people living in northern Mexico at this time probably had closer links to the clans living in the southern U.S. than to the people finding their food in the Mexican highlands.

Chasing seasonal abundance

While humans were nomadic, they did not wander across the landscape aimlessly. Groups were likely to move around a familiar territory, regularly returning to favorite sites, such as the Chiquihuite cave. Their wanderings might also bring them to lagoons and the coast, these visits timed to exploit a seasonal abundance of food.

Mounds of seashells suggest that on these occasions, humans might stay in one place for a considerable length of time. Yet, life was still sufficiently mobile to limit investment in any one site. Caves were popular where they were available; elsewhere, shelter might be whatever roof could be easily constructed with a few branches and then happily abandoned when the group moved on. Without a kiln or oven, there was no pottery or bread.

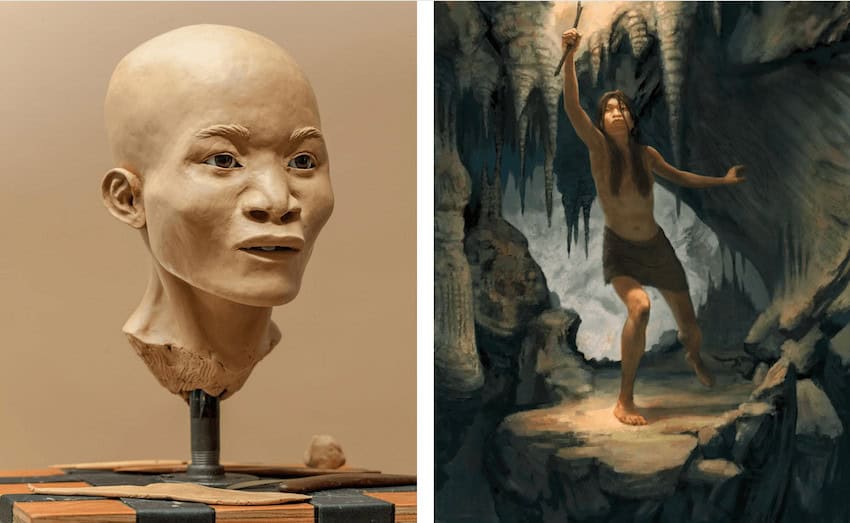

What the discovery of ‘Naia’ in Yucatán tells us

Quite miraculously, we have a human skeleton from this period. There is no evidence our early ancestors had the habit of burying their dead — although that time was coming — and bodies would have been left for scavengers, the bones chewed and scattered. So the survival of the skeleton of a young woman, who scientists have named Naia, was purely accidental.

She was 15–16 years old when she died, just 1.41 meters tall, already a mother, and physically fit from a life of continual exercise, but undernourished. She was in a cave in the Yucatán when she fell to her death. As water levels rose, the cave flooded, and it was 15,000 years before divers, searching for animal bones, found her skull. Numerous other bones were lying close by, and eventually, 80% of the woman’s skeleton was recovered.

When we have a skull, we can recreate a model of what the person might have looked like; dressed in modern clothes, Naia could have strolled down a Mexico City street without attracting attention. Matching her DNA to other finds suggests she belonged to a population that had wandered onto the Bering Strait when it was exposed from the sea and had lived there in isolation for some time before moving into the Americas. As we said, every discovery tends to pose more questions than answers!

Adapting to a new, colder climate and the rise of agriculture in Mexico

9,000 years ago, the climate turned colder and drier, once again forcing humans to adapt. As the game thinned out, amphibians, reptiles and snails played a more important part in the diet. It was a time when stone tools became more numerous and displayed ever finer workmanship. New technologies, such as harpoons, appeared, and there is an argument that some projectiles were so small and finely crafted that they were intended for use with bows and arrows. It was now that humans made the single most important step they would ever take. They started to grow their own food.

This occurred quite independently in many different regions of the planet, at least four of which were in the Americas, including Mexico. Farming should be seen less as a “Eureka” step forward and more as a reaction to a climate that was once again changing and becoming too hostile to rely on food gathered directly from nature.

That, however, is another story.

Bob Pateman is a historian and librarian. He is editor of On On Magazine and the author of several children’s books.