Spiritualism (called espiritismo or “spiritism” in Latin America) — the practice of communicating with the spirits of the dead — originated in Europe, but after being introduced by French educator Allan Kardec (real name Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail) in the 1850s, it quickly spread throughout Europe, the United States and Latin America.

The practice found fertile ground in Mexico, a country that already celebrated Day of the Dead and had an Indigenous population that believed in sorcery, spells, witchcraft and a connection between the living and their dead ancestors.

Given Mexico’s history, it’s not entirely surprising that spiritism had appeal: in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Indigenous people were being converted to Catholicism and told to abandon their own spiritual beliefs.

In the period following Mexico’s independence from Spain and until the Mexican Revolution, there was a schism between the government and the Catholic Church. People needed something to believe in that bridged Catholic doctrine and their long-held beliefs. Spiritism provided that bridge.

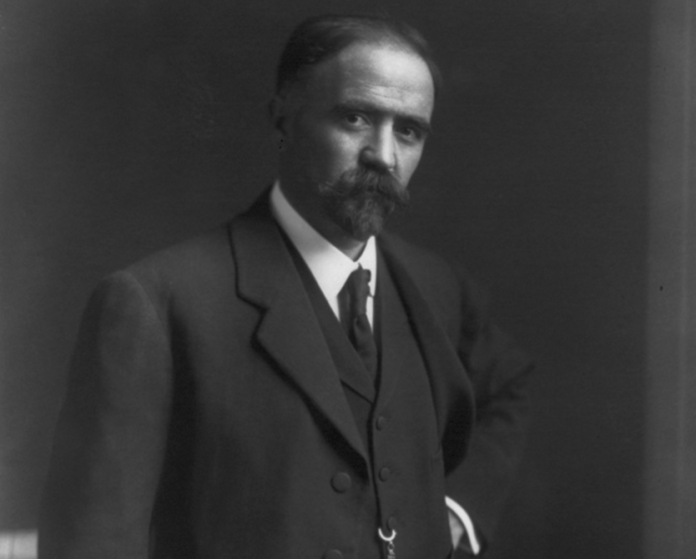

What may be surprising to many is the number of former Mexican presidents, business leaders and other historical figures who embraced spiritism. One of the most famous Mexican spiritists was former president Francisco I. Madero (1911–1913), who believed that spirits guided his political career.

In his memoir, “The Spiritist Manual,” written under the pseudonym Bhima, Madero laid out his personal philosophy based on spiritism. Author C.M. Mayo discovered the book while conducting research on Madero in the archives of Mexico’s National Palace and translated it into English.

Madero — nicknamed the “Apostle of Democracy” — was born in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila, in 1873. Born into a wealthy family, he was educated in the United States and Europe and developed a “positivist” philosophy that prioritized science over religion.

According to his memoir, Madero first came across Kardec’s writings on spiritism in a magazine he found among his father’s books. It seemed to fit with his positivist thinking and led him to return to Europe to explore it further.

While in Europe, he participated in seances and came to believe that he had been gifted with the ability of “mechanical writing” — a way of supposedly communicating with the dead through involuntary/unconscious writing. Upon his return to Mexico, Madero began secretly hosting spiritist sessions and attending seances.

By 1900, he says in “The Spiritist Manual,” he’d had his first contact with his younger brother Raúl, who died in an accident at the age of three. Raúl convinced him to become a vegetarian and become a teetotaller, Madero said.

Later, Madero would claim to also communicate with other spirits, including his uncle José Ramiro — a renowned politician and former governor of Coahuila — and with the spirit of former president Benito Juárez, who Madero said signed his communications as “BJ.”

Madero’s memoir says that Ramiro and Juárez guided him to start the Mexican Revolution in 1910, by encouraging him to write the San Luis Potosí plan, which called for armed revolution to start across Mexico on November 20, 1910. Ramiro supposedly told Madero that he would lead a transformation of the country. Benito Juárez’s spirit helped Madero formulate his ideas of implementing a commonwealth for all people with equality and respect for the rule of law, he said.

Madero made it clear in his memoir that spiritism informed his every action. And, indeed, he seemed a true believer: Juárez’s spirit had instructed him from beyond the grave, and he would respect his messages; after victoriously marching into Mexico City to oust the dictator Porfirio Díaz he respected the rule of law and didn’t just declare himself president. Instead, Madero announced they would conduct a fair and legal presidential election — which he won.

However, heroes of the Mexican Revolution devolved further and further into factionism, some felt the now-President Madero had not moved quickly enough to provide concrete solutions to the people’s problems. His political enemies denounced his spiritism to discredit him. Newspapers began ridiculing him — portraying him in cartoons as a medium at seances communicating with ghosts of the past.

In 1913, when rebels marched into the capital, Madero looked to his former ally army commander Victoriano Huerta for protection – only to be betrayed, arrested, and executed.

Madero was not the only Mexican president who likely believed in spiritism. Former president Plutarco Elías Calles (1924–1928) was also said to have attended spiritism sessions once a month, along with a group of other politicians and intellectuals. Together, they had a medium contact spirits for them. Calles was also said to hold his own sessions to get political predictions from the spirits that would then guide his actions.

These details come from the book “Una Ventana al Mundo Invisible” (“A Window to the Invisible World”), which contains meticulously documented records of dozens and dozens of seances held by the Mexican Institute for Psychic Research (IMIS) from 1940 to 1952, including the names and signatures of members and participants.

The IMIS was founded by a distinguished Mexican banker Rafael Álvarez y Álvarez (1887–1955) who had also been a congressman and senator.

According to the records, not only was Calles — then in retirement — a regular participant but so was former president Miguel Alemán (1946–1952) and several Mexican generals, ambassadors, bankers, a Supreme Court justice, the ex-ministers of Foreign Relations and of Finance and an ex-director of the Bank of Mexico.

The sessions were conducted by Mexican medium Luís Martínez. According to recorded accounts, these seances included a broad spectrum of supposedly supernatural phenomena, including apparitions, spirit guides, and levitation.

These may all have been “parlor tricks,” but they do show the historical belief among Mexicans — including those in power — in seeking out and speaking to spirits, a belief embodied today in the Day of the Dead when the deceased come back to visit their family and friends.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.