Sofía Bassi was born on July 13, 1913, in Mendoza, Veracruz, a city named after her uncle, Gen. Camerino Z. Mendoza. Sofía grew up with her brother, Fausto Celorio, the renowned inventor of the tortilla machine — yes, before him, all tortillas were handmade.

Bassi was married twice; her first marriage gave her two children, Hadelin and Claire. Later, she married Dr. Gian Franco Bassi, with whom she had one child, Franco. Gian Franco took in Haidelin and Claire, and the three children grew up together as siblings. It was for her art — and scandal — for which she would be best known, however.

A pioneer of Mexican surrealism

@artbypilart La pintora surrealista Sofía Bassi fue una exitosa artista mexicana en la década de los 60’s y 70’s, hasta que un trágico incidente la llevó a parar a la cárcel con una condena de once años, de la cual sólo permaneció cinco, ya que el gobierno de la época recibió una intensa demanda del público y de intelectuales para que se le dejase en libertad, ya que se cree que en realidad Bassi se inculpó de un crimen que no cometió para salvar a la verdadera culpable del asesinato: su hija. En toda su estancia en la prisión, Sofía nunca dejó de pintar, al contrario, acrecentó su bagaje artístico y hasta pintó murales dentro del lugar, los cuales aún permanecen. Además es curiosísimo que su estancia no hizo más que AUMENTAR su fama, y cuando salió continuó con una exitosa vida artística que la llevó a pintar un par de murales más y a tener gran reconocimiento en el país. ¿Ya conocías a esta artista? 💜 _________ #art #arte #womaninart #femart #mujeresenelarte #mujeresartistas #8m #diadelamujer #sofiabassi #rodin #surrealismo #mujeressurrealistas #artistasmexicanos #artistasmexicanas #mesdelamujer #8marzo #fyp #fypシ #fypage #fypppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppp ♬ kill bill by sza – lyrics e traduções.

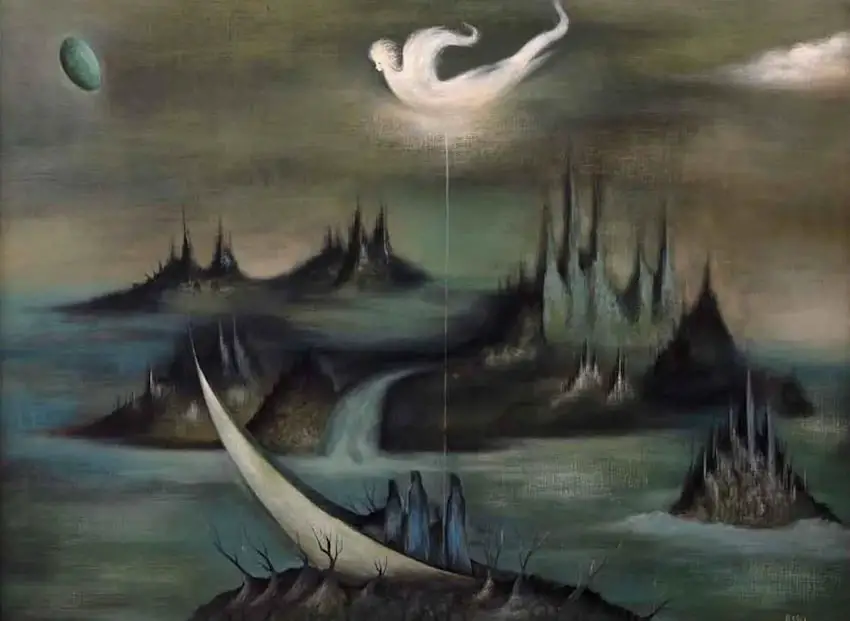

Sofía Bassi is considered the first Mexican surrealist painter, a contemporary of legends Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo. Although Bassi began her artistic career in 1964, she transcended surrealism, creating oneiric works that blurred the boundary between fantasy and nightmare. Her paintings, characterized by green and ocher tones, depicted dreamlike landscapes and ethereal figures that are sometimes scary.

Bassi’s work began to gain attention among wealthy Mexicans in the 1960s and captured the interest of figures such as José Luis Cuevas, who described her as “a painter who really excites.” Her first solo exhibition in 1964 received positive reviews and in 1965 she exhibited at the Galeria Plastica in Mexico. Subsequently, pieces of hers were requested for the Lys Gallery in New York.

The Acapulco scandal

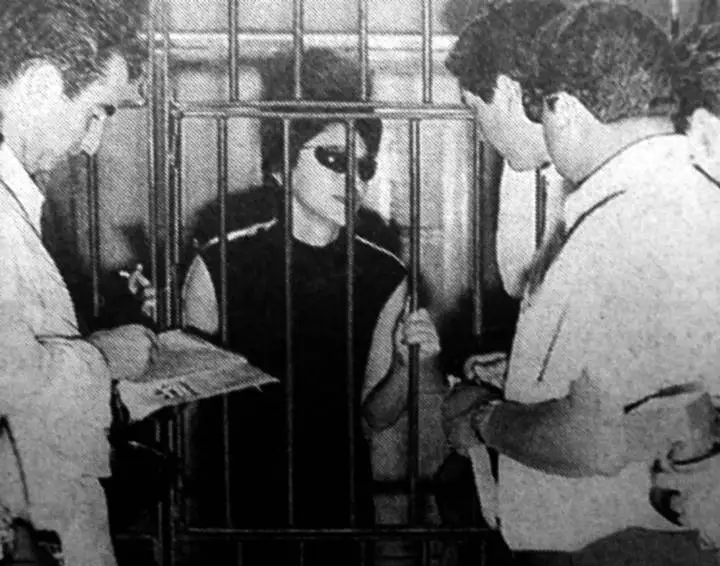

In 1968, just when Acapulco was the epicenter of the world’s jet set, the city’s image was tarnished by a murder. Sofía pled guilty to the murder of her son-in-law, Count Cesare d’Acquarone. This event, which shocked high society in Mexico and Italy, became one of the most relevant events of the year and was covered by newspapers worldwide.

The murder took place on Jan. 3, 1968, at the Quinta Babaji in Acapulco’s Las Brisas neighborhood. Bassi claimed responsibility for the shooting, alleging it was an accident. However, investigations revealed that the count was shot five times in different parts of his body, disproving Sofía’s version.

Some sources suggest that Sofía’s daughter Claire was the perpetrator of the crime and that Sofía took the blame to protect her. The true motivation for the assassination remains a mystery — the most widely accepted hypothesis is that the count sexually abused Claire’s younger brother, which led Claire to kill him. Sofía, upon discovering the crime, decided to incriminate herself and was sentenced to 11 years in Acapulco prison. Claire attempted suicide years later, supposedly leaving a note confessing to the crime, but the letter disappeared, and Claire survived the suicide attempt, although blinded for life.

The news spread quickly through the international press, mobilizing intellectuals from across the country to demand Sofía’s release. Colleagues like José Luis Cuevas, Alberto Gironella, Rafael Coronel and Francisco Corzas always considered her innocent and declared it whenever possible. They all painted the mural “First my homeland, then my life” together with Bassi inside the prison. The mural is 8 square meters and is now at the Municipal Palace in Acapulco.

Thanks to this pressure, Sofía spent only five years in prison. During her incarceration, she stayed in the prison infirmary and devoted herself to painting, creating over 250 works marked with the acronym ELC — “En La Cárcel,” or “In Prison.” These works became portals to other worlds, reflecting his attempt to escape the claustrophobia of confinement.

Art and prison

Sofía used painting to overcome the scandal and tragedy that accompanied her for years. Although society decided to position her in the surrealist movement, her works integrated poetic elements, despite being self-taught. She painted two murals during her lifetime: “First My Homeland, Then My Life” and “Wisdom is Peace” at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Since her first exhibition, Sofía has exhibited in Mexico, the United States, Europe, and Africa. Some of her most important exhibitions are part of the Museum of Modern Art, La Maison de L’Amérique Latine in Paris, the Selma Lagerlöf Museum in Stockholm, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and the Gallery of the Presidency of the Republic in Mexico City.

In 1969, Sofía was invited by NASA to celebrate her work, and she painted “Viaje Espacial,” which astronaut Michel Collins presented for the first time. The work is part of the Smithsonian Museum collection.

In addition to her pictorial art, Sofía wrote several books, including “El Color del Aire,” “El Hombre Leyenda, Siete Cuentos Inserts,” and “Prohibido Pronunciar su Nombre,” a novelized autobiography that reflects part of the Mexican society of the time.

The crime had a brief life in the media, as the world’s eyes turned to the country’s capital for the 1968 Olympic Games. However, Sofía Bassi’s story continues to be a subject of interest because, beyond the morbidity and scandal, her artistic legacy and her ability to transform tragedy into art are things to be honored.

Camila Sánchez Bolaño is a journalist, feminist, bookseller, lecturer, and cultural promoter and is Editor in Chief of Newsweek en Español magazine.