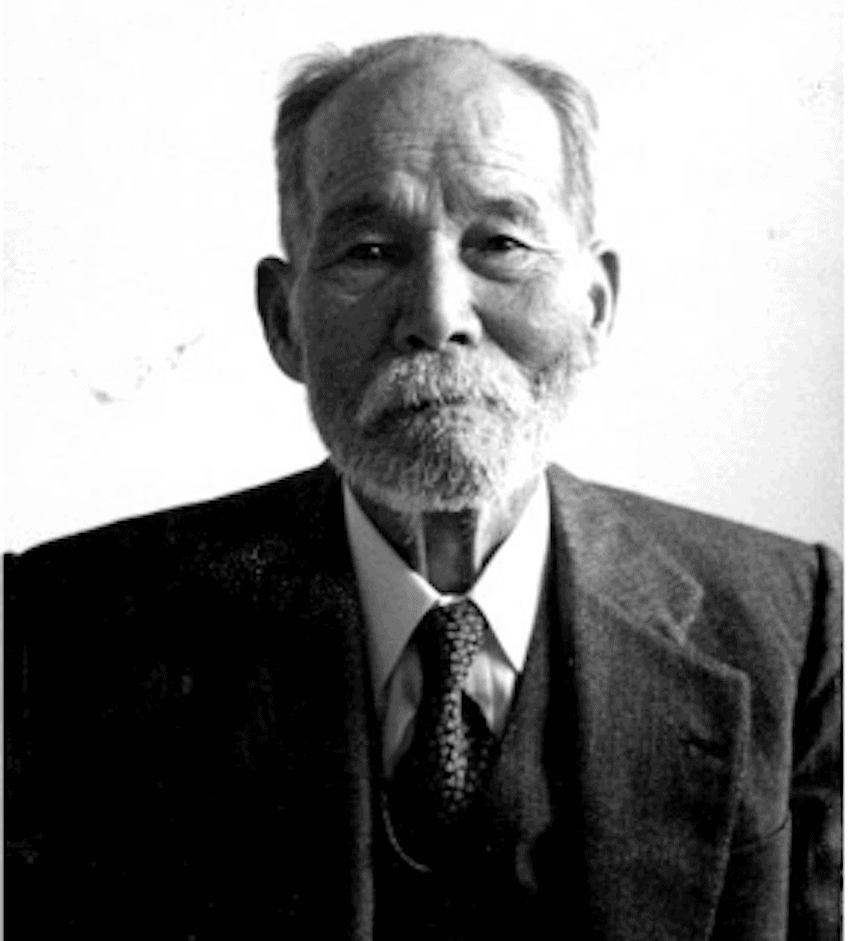

Born in the Shinagawa region of Japan in 1864, Tatsugoro Matsumoto worked as a royal gardener in Tokyo before migrating to Mexico City, where he worked for presidents like Porfirio Díaz and became the landscaper of Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle gardens.

But he is best remembered in Mexico for bringing the purple blossoming jacaranda tree to the capital.

Matsumoto belonged to the 15th generation of landscape architects of the Edo Castle in Tokyo. It was the seat of the military government of Japan during the Edo period (1603–1867) and is part of the grounds of the current Imperial Palace of the Japanese emperor.

“From a young age, Matsumoto learned about gardening and the art of landscaping with different master gardeners who designed and built gardens for the Japanese nobility,” Mutsumoto’s grandson Ernesto told Mexico News Daily.

After eight years of studying Kyoto-style landscaping, Matsumoto received the niwa-shi title in 1884, recognizing him as a master gardener — a distinction similar to a landscape architect of our time.

“Japanese gardens are distinguished by the use of organic lines. They use winding paths to make visitors wander and contemplate the vegetation from different angles, listen to the sound of water in its waterfalls and appreciate the stillness of water in its curvilinear lakes while enjoying the beauty of the Koi fish,” Ernesto explained.

Matsumoto specialized in the placement of rocks to build relaxing waterfalls and lakes and continued designing gardens for Tokyo nobility. These families included the Hosokawa, one of the largest landholdings of the time.

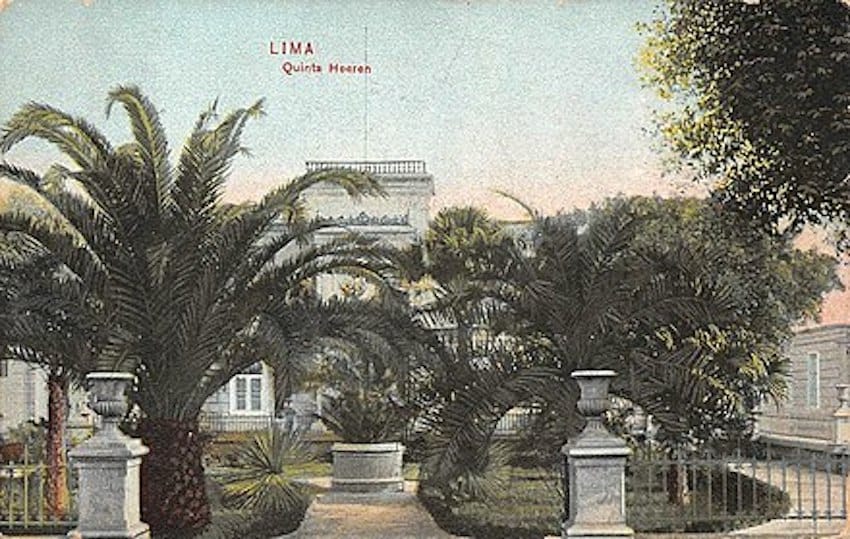

In 1887, Matsumoto met British naval captain John Mathews James, who asked him to design a garden for his residence in Shinagawa. Pleased with the results, he referred him to a German friend in Peru, diplomat Oskar Heeren, who wanted to build a Japanese garden in his magnificent quinta. Born to a Peruvian mother, Heeren worked as Peru’s consul in Tokyo before making Lima his permanent home.

Across Latin America, quintas were rest houses for wealthy families in rural areas that had a vegetable garden or small agricultural plot. Quinta Heeren is currently a tourist destination in Lima.

“Mr. Heeren was in love with Japanese culture,” Ernesto said. “He wanted a garden with waterfalls, lakes and the signature winding paths of a classic Japanese garden.”

At just 24 years of age and never having heard the Spanish language before, Matsumoto accepted the offer and traveled to Lima in 1884. With signs and mimicry, he explained to the quinta’s workers how to install rocks and ornamental plants. Eventually, he mastered the language.

While learning and exploring South America’s native plants, he came across a particular tree that dazzled him with its blue and purple flowers — the jacaranda.

“He fell in love with the jacaranda tree and its beautiful lavender purple [color],” Ernesto said of his grandfather.

It would be a Mexican miner who would bring Matsumoto to Mexico, where he would eventually plant the first jacaranda tree in Mexico City.

“People from around the world would visit Quinta Heeren,” Ernesto explained. “One of them was … Don José de Landero, who became fascinated by Tatsugoro’s garden.”

Landero invited Matsumoto to his hacienda in Huasca de Ocampo, Hidalgo, to build a Japanese garden for him. Matsumoro once again ventured into the unknown, and in 1890, arrived in Mexico for the first time. With a lake and a waterfall, Landero’s Hacienda San Juan Hueyapan also featured bamboo trees, which Matsumoto had sent from Japan.

After finishing his work, he returned to his wife Yoshiko in Japan, who patiently waited for him for almost 10 years. During their time together, he became the father of two sons: Sanshiro and Umakichi.

“He always dreamed of going back to Mexico,” Ernesto said.

After three years in Japan, Matsumoto returned to Mexico alone and without his family (years later his son Sanshiro would join him in Mexico). This time, he would travel with Asian ornamental plants to decorate his gardens. He loaded two ship containers with a variety of plants, and sent them to the United States, to the port of San Francisco. He traveled in a separate ship and arrived in San Francisco on Feb. 1, 1895.

But his shipment kept not arriving.

“He would go to the port every day to watch the ships arrive,” said Ernesto. “But many weeks went by with no sign of his shipment.”

Not knowing any of this but worried that Matsumoto was going to the port every day contemplating suicide, Golden Gate Park Superintendent John McClaren — who himself had once been the park’s head gardener — reached out to Kentaro Domoto, a wealthy Japanese immigrant in the area who with his brothers owned the Domoto Brothers Nursery. McClaren asked him to find out the reason for Matsumoto’s daily visits.

When Domoto told McClaren that the man was a gardener, McClaren offered Matsumoto a position in the park’s new Japanese Tea Garden. He was commissioned to build a small lake and a waterfall, according to Ernesto.

After finishing his work in San Francisco and receiving his shipment three months too late — the plants were dead by that time — Matsumoto resumed his trip to Mexico, where he settled on calle Colima in the Roma neighborhood.

Wishing to grow Asian plants here, Matsumoto sent another shipment from Japan with different varieties of bamboo, azaleas, camellias, lilies, irises, junipers and hinoki cypresses, among many others.

He cared for these plants in his nurseries in México state, Morelos, Puebla and Veracruz. He imported all sorts of plants — not only from Asia also but from South America as well.

“If he didn’t find a specific plant, he would import it and grow it massively to use in his projects,” Ernesto recalled.

Matsumoto’s expertise eventually won him the position of gardener to Chapultepec Castle during the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. During that time, he also participated in the rehabilitation and reforestation of Chapultepec Forest.

After the Mexican Revolution, President Álvaro Obregón asked Matsumoto to beautify Mexico City’s streets. He remembered the jacaranda and imported its seeds from South America to grow in his plant nurseries.

A decade later, President Pascual Ortiz Rubio saw the Japanese cherry trees in Washington and asked Japan to donate trees to Mexico City as they did with the U.S. Matsumoto, however, advised against it since winters in Mexico City are not as cold as in Japan. He warned that the flower wouldn’t blossom.

Instead, he suggested the jacaranda.

“The first jacarandas were transplanted to calle Veracruz in Condesa,” remembered Ernesto. The beautifying project took more than 10 years.

By that time, Matsumoto’s son Sanshiro had already joined him in his thriving Mexican landscaping business, and together they became the florists and landscapers to Mexico’s elite.

Along with his nurseries, Matsumoto set up a flower business in the Roma neighborhood. Today, Florería Matsumoto is still up and running, located at calle Colima 92, and administered by one of his great-granddaughters.

Matsumoto never returned to Japan and died here in 1955 at 91 years old. He left an enduring legacy in Mexico, rooted deeply in each and every of Mexico City’s jacarandas.

By Mexico News Daily writer Gabriela Solís