Accompanying Dr. Peter Jiménez on an archaeological tour in November, I thought he was going to tell us about the Lake Chapala petroglyphs. Instead, he gave us a new perspective on pre-Columbian globalization, demonstrating how very similar the ancient people of Mesoamerica were to us.

Thanks to him, a mystery that had long enticed my curiosity was no longer a mystery.

From my very first days in Western Mexico in 1985, I’ve been fascinated by the Guachimontones, the “circular pyramids” built by the Teuchtitlán culture starting as far back as 200 B.C. Their ruins, which in some cases are remarkably well preserved, can be found in more than 50 locations across Jalisco and neighboring states.

The Guachimontones were ceremonial centers where huge crowds gathered to hear about their traditions, celebrate festivals, dance to music and watch ball games. You can find more about them in my book “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” or in Mexico News Daily.

But then there was the mystery…

Disappearing people

In the past, archaeologists had told me that at some point all the activities around the Guachimontones stopped and the people of the round pyramids had disappeared. By the year A.D. 700, it seemed, there were no longer any traces of them.

These beliefs were dramatically disproved in 2008 when excavations were carried out on the site of what is now the Phil Weigand Interactive Museum at Teuchitlán. “Everywhere we dug,” archaeologist Rodrigo Esparza told me, “we found artifacts proving that Teuchitlán had never been abandoned.”

How was this possible? Those people were still there, but they had clearly forsaken their beloved monuments and customs. Why?

Great civilizations that didn’t vanish

Under the shade of a tall pine tree, near a collection of rocks covered in petroglyphs, Peter Jiménez provided us listeners with clues as to why the builders of the round pyramids had changed their behavior – and perhaps as to why other great civilizations of the past had not really vanished at all.

All those petroglyphs, it seems, had only two main themes: sun and water, the two themes most important to anyone trying to grow corn.

Three cycles were of paramount importance back in those days, Peter told us: the solar cycle, the corn cycle and the ritual cycle. If a culture’s elite could accurately predict the solar cycle, then the corn cycle would be a success. Everyone would be happy, and the elite could rest on their laurels.

If you could predict the summer solstice and the winter solstice, then you could predict the end of the dry season and the beginning of the rains. Likewise, when the harvest was coming and you needed those rains to stop, you could predict their end.

Pecked crosses to keep track of days

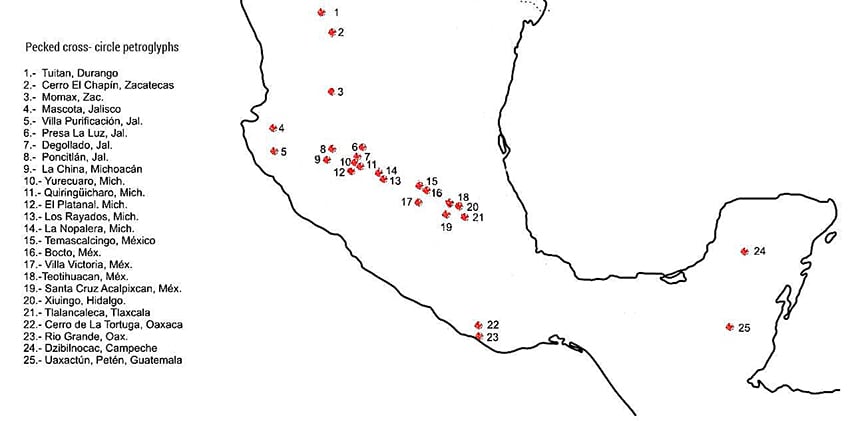

Nearly 400 miles west of Teuchtitlán, the elite of Teotihuacán, it seems, had worked out a way of counting the days. They had developed what is called the pecked cross, a design laid out on a horizontal surface of many small pits forming a cross inside two concentric circles. Among other things, it served as a way to read and keep track of the 260-day calendar.

Teotihuacán’s rulers shared their knowledge with the elite of other areas. Pecked crosses began to appear in various parts of western Mexico – and that wasn’t all. Looking very carefully, archaeologists in this area begin to find clay earspools with the seal of Tlaloc, the storm god associated with Teotihuacán.

“They are very small,” Jiménez told us. “These plugs are so small that no one noticed them for a long time. Now we find them in Cuitzeo, in the center of Jalisco, and even down in Colima and the south of Zacatecas. But the point is: this kind of earspool does not exist in Teotihuacán!”

What we are seeing, says Jiménez, is “the beginning of an institution which unites the elite in an information network, a prestige network. They are markers saying ‘I have a position in a global cosmovision.’”

Jiménez had been talking about the Classic period of Mesoamerican chronology, but now he moved to the Early Postclassic, A.D. 900 to 1200. “Even as far away as southern New Mexico,” said the archaeologist, “we find representations of Tlaloc painted on pots. Now, those people, at the same time, were working turquoise. So between 1000 and 1200, we’re talking about a real boom of globalization in Mesoamerica, especially with respect to trade in cacao and lead-based ceramics.”

“Trade from Chiapas and Guatemala via the coast goes to Chichén Itzá, then Chichén Itzá sends it to Tula and Tula will distribute it to all its allies.”

Imported cocoa in an imported bowl

As a result, says Jiménez, “A campesino in Tula has access to cacao and the jicara (gourd) he drinks it from is imported from Chiapas. Those jicaras, by the way, traveled across the west, all the way to the Pacific coast… and we are talking about bulk quantities.

“While a campesino in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, enjoys a cup of cocoa, turquoise from New Mexico is traveling down the coast and arriving in Chichén Itzá. And copper bells made in Michoacán end up both in New Mexico and in Chichén Itzá. This is globalization.”

High above the shore of Lake Chapala, I got an inkling as to why the people of the Teuchitlán Tradition gave up that tradition, leading archaeologists to believe they had vanished. In reality, somewhere between A.D. 400 and 700, they succumbed to the lure of new gadgets, new fads, new ideas and new awarenesses, shucking off old beliefs and old customs. In other words, they were doing then what we are doing now and have always been doing: out with the hoop skirts, carriages, wigs and typewriters and in with the smartphones. They were just like us!