No Mexico City itinerary is complete without a visit to Chapultepec Park, the expansive urban woodland that holds some of the country’s most grandiose monuments, museums and art galleries. For a park that offers such tranquility amid the frenetic pace of the city, it’s hard to imagine the bloodshed that took place there during the Mexican-American War of 1846 to 1848.

Toward the end of the war, on Sept. 13, 1847, around 2,000 U.S. troops led by Gen. Winfield Scott stormed Chapultepec Castle, which at the time housed the military academy where army cadets trained. It was a decisive U.S. victory which proved pivotal to the American occupation of Mexico City and the subsequent annexation of Mexico’s northern territories, including Alta California, Arizona and New Mexico.

In the U.S. collective imagination, the invasion of Mexico receives far less attention than the Civil War that followed a little over a decade later. But the war was pivotal in U.S. history: it helped solidify the northern country’s expansionism and gave political and geographical weight to the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. Events like the 1836 Battle of the Alamo — technically part of the Texas Revolution — are more widely remembered, perhaps because it was a loss. Defeat invites narrative, giving people a reason to grieve, rally and mythologize.

In the Mexican national consciousness, the Battle of Chapultepec is remembered for the heroic acts of the Niños Héroes (Boy Heroes), six cadets from the academy who allegedly disobeyed Gen. Nicolás Bravo’s order to stand down. Agustín Melgar, Fernando Montes de Oca, Francisco Márquez, Juan de la Barrera, Juan Escutia and Vicente Suárez fought to their last breath to defend the castle. Escutia, the last surviving cadet, is said to have wrapped himself in the Mexican flag before leaping from the castle to his death to prevent U.S. forces from capturing it.

The Niños Héroes’ names and exploits are learned by Mexican schoolchildren as part of the national curriculum set by the Ministry of Education. They are remembered as valiant martyrs who dodged bullets and bayonets, preferring to die for their country than surrender to invading forces. “The message was to love your country to death,” Adolfo Zambrano, a sociologist at the University of Bielefeld, told Mexico News Daily.

At Puerta de los Leones, the main entrance to Chapultepec, the gleaming white Altar a la Patria (Altar to the Homeland) comes into view behind wrought iron gates. Built between 1947 and 1952 from Italian marble, this monument commemorates the Mexican lives lost in the Mexican-American War. The six cadets are represented by towering pillars, each crowned with an eagle and a torch pointing skyward. At the monument’s center stands the Motherland, personified by a muscular Indigenous woman cradling a fallen cadet draped in the national flag. Look closely beyond the monument and you’ll see Chapultepec Castle perched on the hill directly above, with the same flag flying from its peak— a symbolic reclaiming of the narrative, quietly denying that the U.S. flag ever flew there.

Fact, fiction and historical ambiguity

Across Mexico, in nearly every city and town, streets, plazas and even bus stations bear the name of the Niños Héroes. Though their story is widely shared, separating fact from fiction proves more difficult. Myths surrounding the cadets have long been accepted as historical truth. For instance, official government sources still assert that they were the final defenders of the castle, despite a lack of evidence. Their names, now carved into stone, didn’t appear in a history book until 1883, 36 years after the battle.

To begin with, the idea that the cadets were children is misleading. While two were under the age of 18, the remaining four were young adults, including Juan Escutia, who was 20. Juan de la Barrera, 19, actually held the rank of lieutenant in the military engineers. Referring to them as boys heightens the emotional resonance of their sacrifice and positions them as aspirational figures within the national imagination, reinforcing values of duty, loyalty and patriotism.

Their youthful image does more than elevate them as role models. The innocence projected onto the Niños Héroes mirrors the infancy of the Mexican republic itself. Barely two decades after gaining independence from Spain, Mexico in the 1840s was still a fragile and deeply divided nation, struggling to define itself against internal strife and foreign aggression. The story of six brave cadets, young and outmatched, standing firm against a powerful invading force, became a potent allegory for a nation clinging to sovereignty.

Some critics have questioned whether the six Niños Héroes existed in the form remembered today. However, historical accounts suggest that approximately 50 cadets, in an act of defiance, remained at Chapultepec Castle to fight alongside the Mexican Army. Though their decision may have been reckless, it has been reframed as an act of bravery and patriotic sacrifice.

The Battle of Chapultepec was officially commemorated for the first time on Sept. 13, 1882, during the presidency of Manuel González Flores, the four-year period of indirect rule during the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. The ceremony inaugurated the Obelisco a los Niños Héroes monument, which still stands at the foot of Chapultepec Castle and was designed by Ramón Rodríguez Arangoiti, himself one of the cadets captured during the battle. That tradition continues today: each year on September 13 the president reads the names of the Niños Héroes at the Altar a la Patria monument.

Did Juan Escutia really wrap himself in the flag?

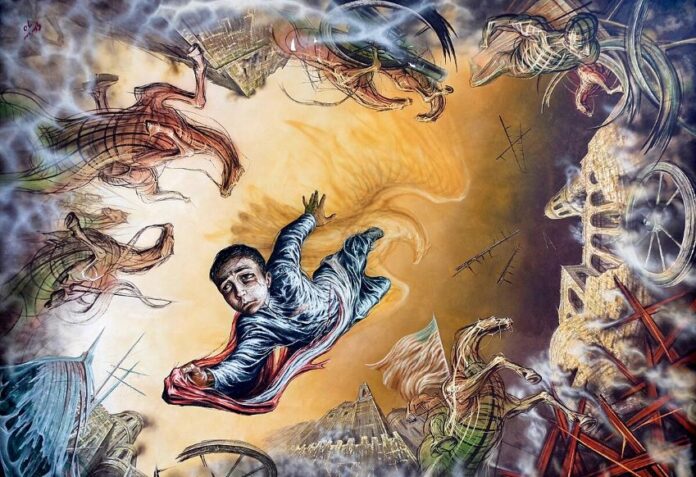

Chapultepec Castle is now a museum, largely preserved as it was during Emperor Maximilian’s rule under French occupation. Visitors who climb the winding path to the top will find more lifelike statues of the Niños Héroes. In the castle’s central stairway, a 1967 ceiling mural by Gabriel Flores depicts Juan Escutia’s leap to his death, wrapped in the Mexican flag. But did it really happen that way?

Evidence suggests Escutia may not have been a cadet at all, but a soldier in the San Blas Battalion. That unit, founded in Nayarit in 1823, was led during the Battle of Chapultepec by a lesser-known figure named Felipe Santiago Xicoténcatl. According to eyewitness accounts, Xicoténcatl was gunned down by U.S. forces while trying to keep his battalion’s flag aloft. As he fell, his comrades wrapped his body in the flag and buried him with it.

It’s possible the story of Xicoténcatl was later transferred to Escutia, who was reimagined as a boy to heighten the drama. In 1947, Xicoténcatl’s remains were exhumed and eventually entombed alongside the remains of six people found in Chapultepec and alleged to be the Niños Héroes beneath the Altar a la Patria monument at the park’s entrance– another claim that proves difficult to substantiate.

Notably, Xicoténcatl was Indigenous, a Nahua officer from Tlaxcala, while the Niños Héroes are almost always depicted as light-skinned, European-looking cadets. This contrast reveals how post-independence Mexican nationalism often privileged a Europeanized ideal of citizenship. By transferring the story of patriotic sacrifice to Juan Escutia, a figure reimagined as youthful and white, the myth erased the Indigenous person’s contribution.

What do the Niños Héroes tell us about Mexico?

Regardless of how much of their story is true, the enduring prominence of the Niños Héroes reflects the early nation-state’s need to transform narratives of loss and sacrifice into unifying myths. Their legend offers consolation for the loss of nearly half of Mexico’s national territory following the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and continues to have emotional resonance for Mexicans today. Recalling his childhood in a 2005 essay, Mexico City-born literary critic Guillermo Sheridan remembers the influence of the Niños Héroes: “That there might be boys who, besides being boys, were heroes, added up to a pressing demand on my own potential heroism. Many a time did I dream of myself duly chopped up and distributed over several monuments for having defended the peaks of the Popocatépetl to the end from some foreign scoundrel.” The power of the story lies not only in what it commemorates, but in how it continues to shape national identity. As Adolfo Zambrano of Bielefeld University put it, “There’s a part of me that believes the myth actually happened despite the lack of evidence.”

When we hear talk of President Donald Trump’s renewed expansionist ambitions, it’s tempting to treat such rhetoric as an anomaly. However, a closer look at this period in Mexican history reveals that territorial aggression has long been a tenet of U.S. foreign policy. The wounds of the Mexican-American War run deep in Mexico’s collective memory, and they continue to shape how the country understands its relationship with its northern neighbor. The myth of the Niños Héroes is one way of processing that legacy— recasting defeat not as humiliation, but as a heroic model of sacrifice.

Shyal Bhandari is a British-Indian writer caught in a whirlwind romance with Mexico. He holds an MPhil in Latin American Studies from the University of Cambridge. His writing has appeared in publications including Vogue, Ojarasca, Little White Lies and Asymptote Journal. In 2019-2020 he ran a series of literary workshops with Indigenous poets in the south of Mexico with the support of the Royal and Ancient International Scholarship.