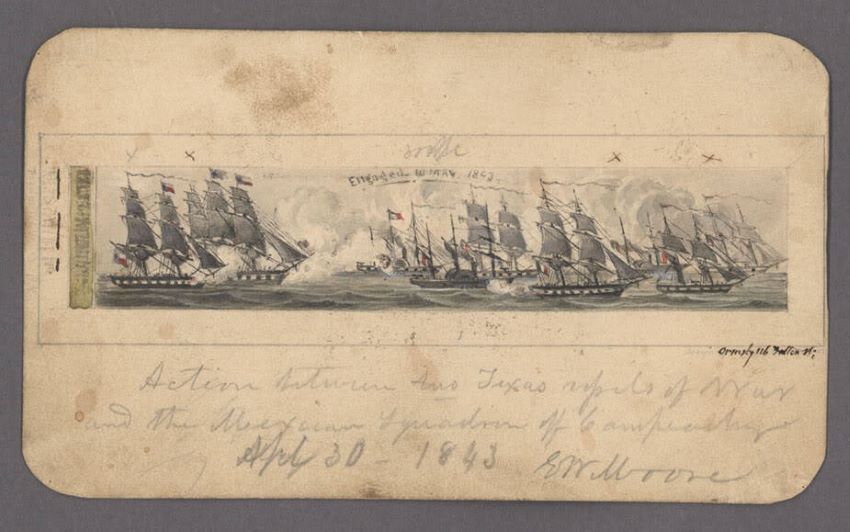

April 1843: a small flotilla of ships are cruising along the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula, which has seceded from Mexico. The ships are flying the Mexican flag, and their intention is to do battle with the Texas Navy vessels that have been spotted in the area in what will later become known as the Naval Battle of Campeche.

In 1843, Mexico is struggling with an economy still devastated by the War of Independence, political instability and crushing debt. Yet at the heart of the Mexican force are the Guadalupe and Moctezuma, the two most modern ships in the world. How these vessels came to belong to the Mexican navy is a story of both technology and politics.

The crisis of the 1840s

The mid-1800s were a turbulent time around the Gulf of Mexico, with the borders we recognize today not yet established. Texas had been independent for just seven years, and it was uncertain if it would be annexed by the United States, continue as an independent nation or even face reannexation by Mexico. The Mexican government saw enemies on all sides: to the north were the United States, Texas and their filibusters. Across the Atlantic were the menacing imperialist powers of France, which had attacked Mexico in 1839, and England, which had a colony in the southern Yucatán Peninsula. Spain itself had attempted to reconquer Mexico through the 1820s and only recognized Mexican independence in 1836.

Then there were the internal enemies. Texas had seceded from Mexico in the midst of a wave of federalist revolts and secessionist movements sparked by the establishment of the Centralist Republic in 1835, and Yucatán followed a few years later. In October 1841, the state’s Chamber of Deputies declared independence, establishing the Republic of Yucatán for the second time. The two breakaway republics struck a deal: the Texas Navy would defend Yucatán from Mexican attacks by sea, and in exchange Yucatán would pay Texas US $8000 a month.

Both to defend itself and to retake its rebel states, Mexico needed a modern, professional military, and the threat posed by Texas and Yucatán in the Gulf meant that the country urgently needed a new navy. This left Mexico in a weak position, for in 1839 the French had stormed Veracruz and seized most of their fleet. The government of Antonio López de Santa Anna, who returned to power in the same month that Yucatán declared independence, would have to rebuild its navy with limited funds. Still, they did not need a great fleet of ships-of-the-line and went shopping for a cheaper alternative in smaller ships.

The revolution in ship building

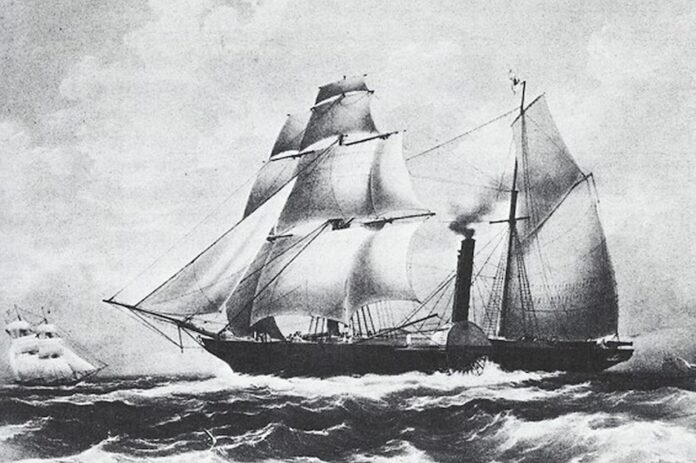

It was the right time to be in the market, for three new technologies were revolutionizing ship building: the iron hull, the steam engine and guns that fired exploding shells. If these technologies worked, great warships would no longer sit idle when the wind dropped. They would no longer have to pound each other for hour after hour with cannonballs. Maneuverability and destruction would reach new levels.

Several British companies were experimenting with steamships. However, the man who finally put iron and steam together was John Laird. He had given up a fledgling career in law to join the family company that made steel boilers. It was Laird who saw that the same technique used to make boilers might be used to construct a ship’s hull. However, it was by no means certain that iron would be a better material: centuries of experience had made the wooden warship an incredibly tough construction, while early experiments suggested iron plating did not stand up to cannonballs particularly well.

Steam engines also posed difficulties: early designs swallowed coal at a frightening rate. Like any new technology, steam engines were also temperamental. As a result, the first steamships carried a full set of sails, both to save coal when there was a favorable wind and as backup should the engines break down. Moreover, the first steam ships were driven by paddles; large, fragile objects that sat in the middle of ships, where they were most likely to be hit. Yet the advantages of steam, more or less freeing a ship from the unpredictable wind, were obvious.

Mexico buys a navy

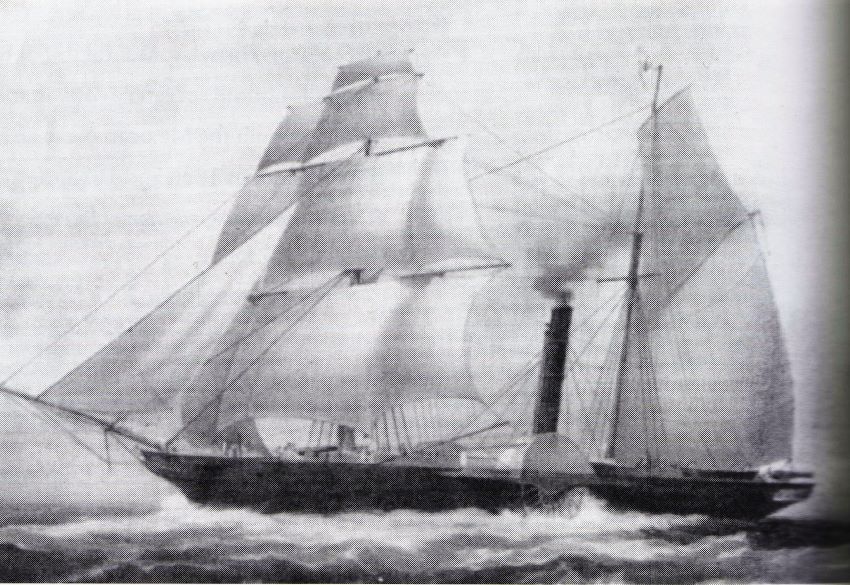

Having made a few small steam-driven vessels, Laird took a gamble and started work on a larger ship. When finished, she would be 183 feet in length with a displacement of 878 tons. The hull would be clad in iron and she would be driven by steam via large side paddles. With the British Navy showing no interest in purchasing his vessel, Laird welcomed an overture from the Mexican government. For firepower, the Mexicans turned to France, where the navy was now using the Paixhans gun, the first of a new generation of weapons that fired explosive shells. As Laird’s shipyard worked to finish the ship, now named the Guadalupe, the Mexicans located a second steam-driven paddle ship being constructed in the Blackwall Yard of London. She was also purchased and christened Moctezuma.

These purchases caused a diplomatic rumpus, with William Kennedy, the Republic of Texas’s consul general in London, protesting to the British government. After considering the protest, the British approved the sale of the ships as merchant vessels, fully aware that the guns they carried in their hulls would be fitted once they had crossed the Atlantic. Britain was walking a fine line in its attempt to be neutral.

When the Texans learned that the ships would not only be sold to Mexico but that British officers were to command them, the issue was brought before the English courts. The sale, said Texas, was a violation of the Foreign Enlistment Act, which provided for confiscation of ships armed to make war against a country at peace with England. Customs officials detained the Guadalupe until the issue could be settled. British authorities eventually decreed that if the large guns were removed and the crew reduced to that of a merchant vessel, she would be free to sail.

War in the Gulf

When the Guadalupe set sail on July 4, 1842, under the command of Captain Edward Charlewood, her crew was still uncertain of their destination, although they seemed to have expected that it would be China. On July 18, while at sea, crew members were informed for the first time that they were heading for Mexico. “That place is blockaded by a set of half-breed Yankees, who call themselves Texans,” said Charlewood. “I am determined to break my way through.”

In Mexico, negotiations were breaking down between the national government and the Yucatecans, who would only rejoin the republic on the condition that Yucatán could retain a degree of autonomy, including keeping trade relations with Texas. In August, Santa Anna decided to retake the peninsula by force and sent ships to seize Ciudad del Carmen.

It was December before the Moctezuma finally sailed. In January, she began transporting Mexican troops from Veracruz to Yucatán and at one point boarded a Texan ship.

Texans were eyeing Mexico’s new ships with reservations, not at all certain that Mexico didn’t plan a seaborne attack on their young nation. The Texan navy was no better equipped than the Mexicans, and certainly no better funded. Indeed, they only had two ships of any size, the sloop-of-war Austin and the brig Wharton. Texas’ second president, Sam Houston, had been elected in December 1841 and had been opposed to the defense deal with Yucatán from the beginning. Considering the Texas Navy impractical and expensive, Houston ordered the fleet back to harbor to be sold. This was unacceptable to Texas Commodore Edwin Ward Moore, who had accrued massive personal debt trying to keep the fleet afloat.

With his forces dwindling, Moore found a solution that would save his ships: he struck a deal in which the Yucatecans would pay his fleet directly to protect the peninsula. Moore ignored his own government and sailed to lift the Mexican naval blockade of the port of Campeche in the spring of 1843.

The Battle of Campeche

The Mexicans, hearing that Moore had arrived off the Yucatán coast, came searching for him. In addition to their two steam ships, the Mexican Navy sent four sailing ships. Having sailed south in light winds the Texan fleet reached the Yucatan coast to learn that Mexican ships had been sighted some 50 kilometers away. Come daylight on April 30, the Texans spotted the Mexicans steaming towards them.

The Texans were the more aggressive — to be expected, since their commander had defied his own president to be there — while the Mexicans made full use of the mobility their steam engines gave them. They kept the Texans at a distance and turned into the wind whenever they wished to break off the action. There was an hour of long range firing, but by mid-morning the wind was dropping, making the Texans’ task even more difficult. For the Mexicans, the fuses of the Paixhans shells proved frustrating, with many not exploding. A day of skirmishing had been indecisive.

The fleets clashed again on May 16, when the Texans were able to get closer and the two Mexican ships suffered heavy casualties. Commander Charlewood, in charge of the Guadalupe, still felt his ship had stood up well. The Guadalupe, he later wrote, had been hit six times without any great damage and had made a good gun platform. It was their accurate shooting, he wrote, that had forced the Austin out of the battle. At this point both sides broke off and sailed for home where the ships could be repaired and replenished. The Texans were greeted as heroes on their return, and a court-martial cleared Commodore Moore of piracy.

The two Mexican steam ships continued to give service, but when Yucatán moved to rejoin the republic, they were no longer required. When Mexico needed funds during the 1847-1848 war against the United States, the Guadalupe and Moctezuma were sold to the Spanish Navy and delivered to Cuba. Renamed the Castilla and León, they would see further action in the Mediterranean. It was a surprisingly long career for ships that had pioneered such new technology and which, for a short while, had made the Mexican Navy the most modern in the world.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.