When lists of all-time great boxers are made, Rubén Olivares is usually included. Either he’s ranked as one of the best five men to have boxed at bantamweight or one of the best five world champions that Mexico has ever produced. His career spanned 24 years and 109 fights, and caused an immeasurable amount of excitement. Olivares was, above all, a fighter who excelled at knocking his opponents out, sometimes having to get off the canvas himself to do so.

Born in the coastal state of Guerrero, his family moved to the Bondojito area of Mexico City in 1947. It was a time when thousands of Mexicans were leaving the countryside, and the slum areas around the city were expanding faster than the government could provide adequate housing or services. Olivares became a tough boy on tough streets. Siblings died, his father left to find work in the U.S. and he was thrown out of school for fighting. According to boxing folklore, the headmaster once offered to present his graduation diploma early, on the condition that Olivares never come back to the school.

How Rubén Olivares began his boxing career

He tried his hand at carving wooden figures, a career for which he had little talent. Then, he and a friend decided the one thing they could do was fight, so they walked down to the local gym. Many boxers start as amateurs for fitness, or to toughen up, and then find they are good enough to turn professional. The day Olivares first entered the gym, he already had a professional career in mind.

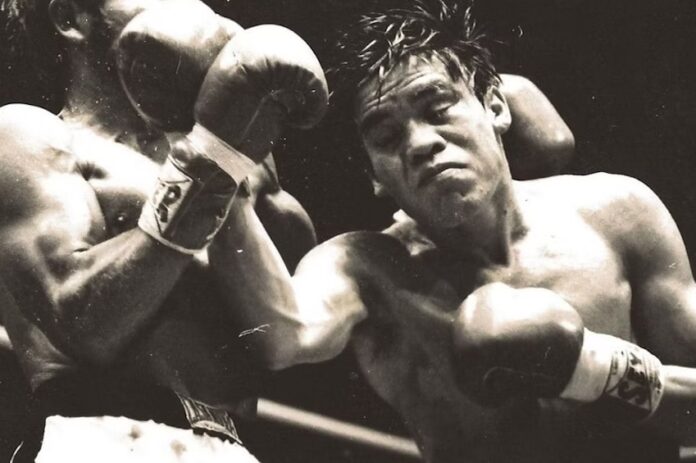

He built up a reasonable record in the amateurs, including a Mexico City Golden Gloves title. But having missed his chance to compete in the 1964 Olympics, he saw no point in continuing to fight for free. At just 17 years of age, he had his first professional fight, beating Isidro Sotelo in Cuernavaca. It was the first of 24 consecutive knockout wins. Apart from his winning record, Olivares had that special star quality. While many boxers wear out their opponent, slowly mastering them until you sense a knockout is coming, from the moment Rubén stepped into the ring, you knew a knockout punch could come at any moment. Whatever else might happen, fans were not going to get a dull fight.

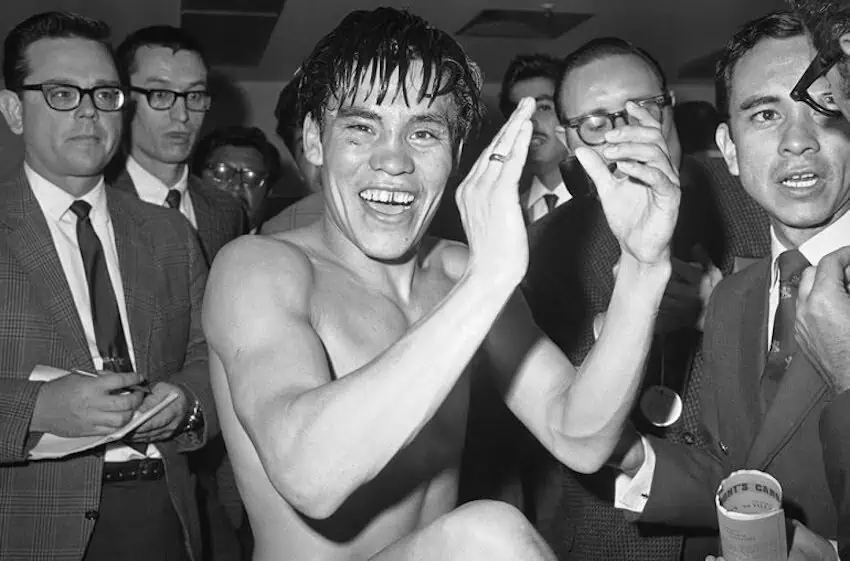

With money coming in from fights, Olivares did not slow down when he left the ring. He was noted for his love of tequila and women. However, this lifestyle only made his fans love him more. As the wins accumulated, Ruben started to get attention beyond Mexico. The Los Angeles Times once described him as having “a smile that stretched from ear to ear and thunder in both hands.”

The man with thunder in both hands

Another young Mexican bantamweight catching headlines at this time was Chucho Castillo. He was noted for his quiet, almost shy approach to life, working ruthlessly in the gym but then quietly slipping away. He was one hell of a boxer and in December 1968 traveled to Inglewood, California, to fight World Champion Lionel Rose. The 10th round saw Rose knocked to the canvas, a moment that convinced the many Mexicans in the audience that their man had done enough to win the title. However, when at the end of 15 rounds, the referee raised the Australian’s arm in victory. There was first surprise and then anger. The riot that followed put 14 fans and the referee in the hospital. Five months later, Olivares came to Inglewood, where he beat Olympic champion Takao Sakurai of Japan in a title elimination bout.

He was now set to meet Rose for the world title, which would once again be fought in California. The first round was even as the two men sized each other up. This was followed by an action-packed second that started with the fighters exchanging blows. Slowly but steadily, the brawl turned in the Mexican’s favor, and close to the bell, Rose was knocked to the canvas. The Australian got to his feet and fought on, but from this point it was a case of not who would win, but how long Rose could last. It ended in the fifth, Olivares becoming world champion at the age of 22.

The trilogy of fights with Chucho Castillo

All of Mexico now wanted to see Olivares fight Castillo. The former delayed the showdown by taking a few easy fights, but in April 1970, the two Mexicans stepped into the Inglewood ring for what would be the first of three fights that would define their careers. Olivares won the first clash on points, but it was close enough to justify a return. This time, he received a badly cut eye in the first round, a wound he claimed was from a clash of heads, something the Castillo camp denied. The referee kept checking the cut and finally stopped the fight in the 14th. It was Olivares’ first defeat in five years and 63 fights.

It is possible that by then, he was already in decline. Olivares notoriously hated training, and one reason his management team kept him fighting so regularly was to keep him occupied and away from parties. Not that the management had to push him into the ring. The money Olivares got from each contest quickly disappeared, lost in rip-offs, taxes, bad investments, and gifts to his relatives and friends back in the barrio. His bank balance always needed one more fight.

The end of Olivares’ career

By now, he was no longer putting the same effort into the gym work, while his party lifestyle meant he was increasingly struggling to make the weight limit. Yet Olivares was so talented and so proud in the ring that at first the decline didn’t show. In April 1971, he fought Castillo for the third time, surviving an early knockdown to win on points. He seemed back on form and won his next six fights. However, those around him were increasingly worried about his attitude and his playboy lifestyle. In March 1972, he met Rafael Herrera. It was a fight neither man wanted. Olivares was out of shape, and Herrera had been sick. When Herrera later won with an eighth-round knockout, Olivares was still surprisingly upbeat. He had not, he announced, lost the bantamweight title, but had started his pursuit of the featherweight title.

However, his life was growing increasingly wild. There is a story that while he was preparing for one fight, he and his opponent passed each other in the street. His rival was going out for an early training run just as Olivares was coming in from a disco. It was also at this point that the boxer started to get into movies, starring in “Nosotros Los Feos” and getting numerous other smaller parts. Despite all the distractions, Olivares won three more world titles. He beat Bobby Chacon for the NABF featherweight title in 1973, Zensuke Utagawa for the WBA featherweight title in 1974, and Chacon again for the WBC featherweight title in 1975. He finally left the ring in 1981, having lost three and drawn two of his last five fights.

Life after boxing

His life since then has had its ups and downs. On the downside, there was a marijuana-related arrest. In contrast, there was his induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. There were some television roles, but financially, his post-boxing career brought tough times. In his later years, Olivares was a regular in the Mexico City mercado, selling boxing memorabilia and autographs. There are children and grandchildren, and at 74, he is still active, still has that captivating smile, and still has the respect of the people who recognise him in the street.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.