It’s the early 1940s, and the art world is in trouble: The Nazi regime has officially classified Surrealism — an artistic movement born in 1920s Paris — as “Degenerate Art” and has marked it for destruction. Galleries are closing by the dozen, pieces are being seized from state-owned museums and artists themselves face arrest or worse. Leading figures in the movement, like Max Ernst, are repeatedly harassed by the fascist governments sweeping across Europe.

Those who can, leave — but to where? Circumstances during the war didn’t leave much room for preference. The United States maintained strict immigration quotas — created under the National Origins Act of 1924 — with no special provisions for political refugees. Britain was under siege.

But one country offered something different: Mexico.

Why Mexico became a refuge for Surrealists

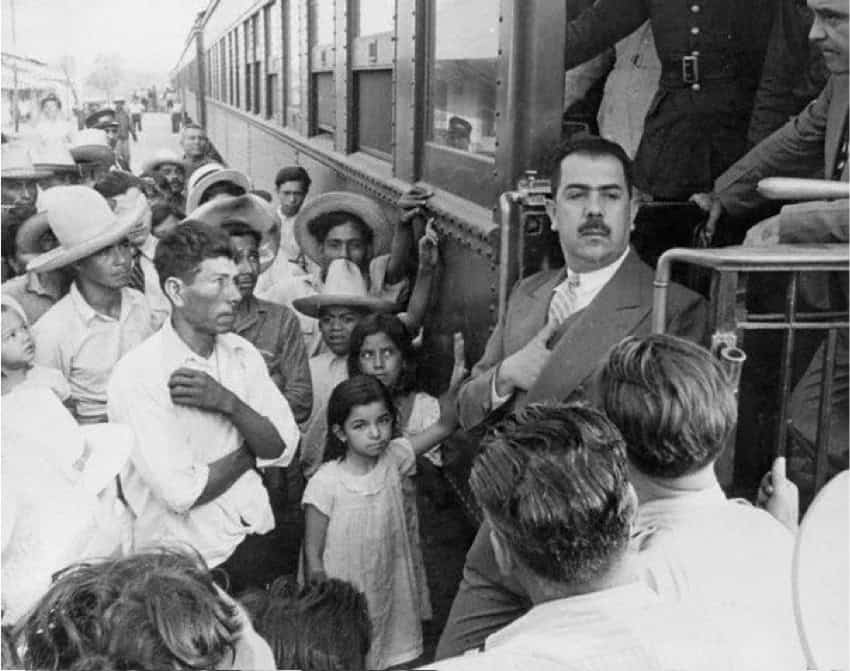

Mexico offered an appealing refuge in three ways. For one, President Lázaro Cárdenas had established an asylum policy during the Spanish Civil War — anyone who could escape Franco’s Spain would be granted entry to Mexico. Also, Mexico’s wartime economic boom had created opportunities for artists to find patronage and exhibition spaces. Finally, Mexico City had established cultural infrastructure that included galleries like Galería de Arte Mexicano, workshops like the Taller de Gráfica Popular and a vibrant artistic community.

Over 20,000 Spanish Republicans arrived by 1940.

When French poet and writer André Breton, a cofounder of the Surrealist movement, visited in 1938, he declared Mexico “the most Surrealist country in the world.” But getting to this promised land would require harrowing journeys that would change both the artists and Mexico City’s artistic landscape forever.

Three dramatic escapes across the Atlantic

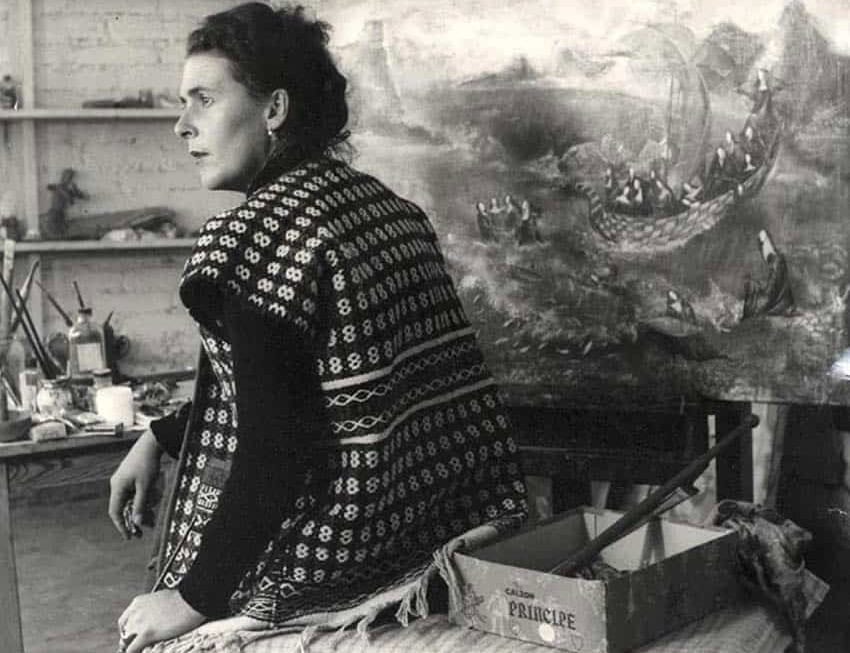

Leonora Carrington’s escape reads like a psychological thriller: The young British artist had been living with Max Ernst in southern France when fascist police arrested him. Alone and terrified, Carrington fled to Madrid, triggering a complete mental breakdown. She was committed to a psychiatric hospital, where she endured horrifying treatments that would later influence her surrealist paintings.

Upon her release, Carrington went to Lisbon and connected with Renato Leduc, a Mexican poet and diplomat who offered her a marriage of convenience to escape. Mexican consulate to France Gilberto Bosques — often hailed as “Mexico’s Oskar Schindler” for issuing at least 1,500 life-saving visas to Europeans escaping fascism — granted her entry. Carrington sailed to New York, then finally to Mexico, to start over.

Spanish artist Remedios Varo’s journey began earlier. After fleeing Franco’s regime in 1936, she and her activist boyfriend, poet Benjamin Péret, found themselves starving in Nazi-threatened Paris, living under constant threat of arrest.

When France fell, they managed a harrowing escape to Mexico through Marseille, the last open port before Europe’s complete closure.

Austrian painter Wolfgang Paalen and French poet Alice Rahon took a circuitous route through the Pacific Northwest, where Paalen collected Native American artifacts even as they ran for their lives. They arrived in Mexico City together in September 1939, personally invited by Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

The reception: Mexican artists’ mixed reactions to European refugees

These European creatives arriving in Mexico City entered a complex artistic battlefield. Some welcomed them with open arms; others gazed upon these foreign intellectuals with deep suspicion.

Inés Amor, director of the Galería de Arte Mexicano, became the refugees’ most powerful ally. Her gallery had been founded in 1935 as Mexico City’s first contemporary art space and was renowned as the country’s most influential venue. Amor understood that these refugees brought international connections and artistic innovations that could elevate Mexican art on a global scale, and provided exhibition opportunities – she became Leonora Carrington’s primary dealer in 1956.

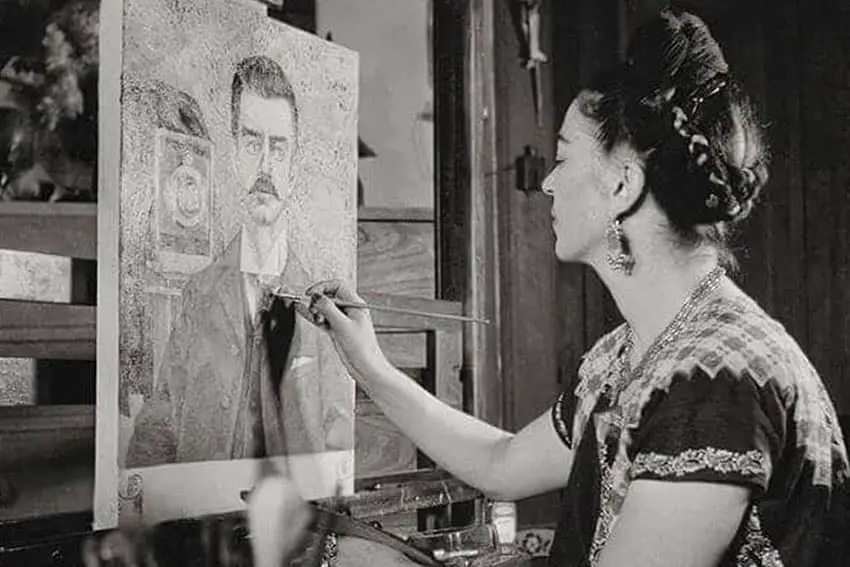

On the opposite side of the spectrum was Frida Kahlo, who famously and fiercely resented the influx of fresh artistic talent. Despite hosting André Breton and other Surrealists in her famous Casa Azul, she had much to say when they weren’t listening.

Letters to photographer Nickolas Muray are fueled with anger, including statements like “They are so damn ‘intellectual’ and rotten that I can’t stand them anymore.” She called Breton “an old cockroach” and declared she’d rather “sit on the floor in the market of Toluca and sell tortillas than have anything to do with those ‘artistic’ [expletives] of Paris.”

Kahlo’s resistance wasn’t just personal. She also had strong feelings about being categorized within the confines of a European movement.“’I never knew I was a Surrealist until André Breton came to Mexico and told me I was one,” she reportedly told her dealer in 1938.

A creative explosion: Surrealism meets Mexican culture

The deeper conflict lay between Mexico’s nationalist Muralists and the international Surrealists. The Muralists were creating a new Mexican identity for a post-Revolution Mexico, exactly at a time when nationalist themes were downright traumatic for the Surrealists. Mexican muralists focused deeply on portraying the realities of Mexico’s pre- and post-colonial history and elevating its Indigenous heritage.

Surrealists, by contrast, wanted to face anything but reality – after all, they had just fled a real-life nightmare and used dream interpretation and mental imagery to escape those horrors. Meanwhile, as Marxism split into factions, the groups supported different sides and the Surrealist community faced marginalization.

Despite the tensions, something extraordinary happened when European Surrealism collided with Mexican culture — the art world transformed.

Exposición Internacional del surrealismo

Wolfgang Paalen organized the “Exposición Internacional del surrealismo” at Galería de Arte Mexicano in January 1940. All the greats of the time were on the walls: Dalí, Ernst, Rivera, Varo, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Jean Arp, René Magritte and Meret Oppenheim. The show unveiled Frida Kahlo’s monumental “Las dos Fridas,” a quintessentially Surrealist painting (despite her resistance to the label).

What made this show stand out was Paalen’s decision to display the contemporary works alongside pre-Columbian artifacts from Rivera’s extensive collection. This bold act bridged the gap—metaphorically and conversationally—between Mexican and European artists.

Women also faced a whole new world of artistic freedom. In Europe, female Surrealists had been largely confined to supporting roles. Mexico offered them the creative independence they’d never before experienced. Varo, Carrington, and Hungarian-born photographer Kati Horna formed an intense friendship based on shared fascination with Indigenous cosmologies, alchemy, metaphysics and the tarot. Artist Alice Rahon created ethereal paintings inspired by ancient Mexican codices. Varo developed her signature style that blended science and mysticism. Carrington began incorporating Mexican spiritual traditions and Celtic mythology into her fantastical paintings.

The legacy: how Surrealist refugees transformed Mexico City’s art scene

The arrival in Mexico of Surrealist refugees helped turn the nation’s capital into one of the most dynamic and cosmopolitan cultural centers in the Americas during the 1940s.

The transformation began in the neighborhoods where they settled: Roma became the epicenter of international artistic life, flourishing with salons, galleries and the bohemian culture that defines the Mexico City neighborhood to this day. Remedios Varo, her husband and Horna lived and frequented cafes near Orizaba. Carrington lived on Calle Chihuahua 194 for 60 years; her former home is now a research center housing her own personal archive.

Today, Roma is home to dozens of cutting-edge galleries like the Olivia Foundation; the bordering Condesa neighborhood hosts international spaces like Mexico City’s outpost of the König Galerie. According to Mexican artist and Casa Wabi founder Bosco Sodi, the capital’s gallery scene is “buzzing with energy reminiscent of Berlin two decades ago.”

Nearly eight decades later, Mexico City stays true to its roots as an artistic haven for refugees. Since 2007, the capital has been an active member of the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) through Casa Refugio Citlaltépetl, where endangered creatives find the same outlet that those wartime refugees once received. And so Mexico City continues a tradition established in the 1940s, proving that some cities are destined to be refuges where art and safety intersect.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog or follow her on Instagram.