Founded in 1542 as a Spanish outpost, San Miguel de Allende thrived during Mexico’s colonial period, bolstered by the wealth of nearby silver mines. This influx of riches led to the construction of magnificent mansions, churches, and public buildings, reflecting the city’s prosperity. It was in the days of New Spain that the history of the Instituto Allende truly begins, with a man named Don Manuel Tomás de la Canal.

De la Canal was a wealthy man born in Mexico City to Spanish parents. He moved to what was then known as San Miguel el Grande, drawn by the town’s growing importance as a colonial settlement and its thriving silver trade. In 1734, he built an impressive manor house that reflected his status and ambition. This immense property was not just a residence but a grand estate that included a spacious home, a flourishing orchard, and a vineyard, all enclosed within a massive stone wall. By the time he passed away in 1765, he had built many of the grand landmarks that still stand today.

A church that never was

In 1809, the Discalced Carmelite nuns of Querétaro acquired the building with plans to convert it into a neoclassical-style church. They hired renowned master architect Manuel Tolsá for this task. However, two major challenges prevented the nuns from achieving their goal. First, the War of Independence broke out in September 1810 causing widespread disruption and halted construction. Second, the nuns lacked a royal certificate from the Spanish Crown, which was required to legally use the building for religious purposes. As a result, their plans were abandoned, and the building sat unused for decades.

War, decline, and near abandonment

The War of Independence (1810-1821) and the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917) took a heavy toll on San Miguel de Allende. The once-thriving silver mines, which had sustained the town’s economy, were forced to shut down, leading to widespread hardship. The social and political unrest of these periods deepened the decline, prompting many residents to leave in search of better opportunities. As people moved away, the town’s grand buildings fell into neglect, and by the early 1900s, San Miguel was on the verge of becoming a ghost town.

Renewed prosperity

In 1926, the Mexican government stepped in and declared the town a national historic monument. This designation marked a turning point, showing a commitment to preserving its heritage. Strict regulations were put in place to protect its colonial charm, setting the stage for the town’s revival.

In 1927, inspired by intellectuals Alfonso Reyes and José Vasconcelos, Peruvian artist and diplomat Felipe Cossio del Pomar visited San Miguel de Allende and was captivated by its unique quality of light. Nearly a decade later, he followed his dream and founded the School of Fine Arts (Escuela Universitaria de Bellas Artes).

Cossio established the Bellas Artes school in the former convent of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception (now known as “Las Monjas”) that was built in 1765 by María Josefa Lina de la Canal, Don Manuel de la Canal’s daughter. This convent had been seized by the government following the Reform Laws of 1860 and was being used as military barracks.

The journey of Stirling Dickinson

Stirling Dickinson, born in 1909 in Chicago into a prominent family, was a talented artist and architect with degrees from Princeton University. Dickinson and his classmate, Heath Bowman, embarked on a six-month journey through Mexico to write a travel book. Their trip through Mexico turned into a permanent resident situation when José Mojica, a renowned Mexican opera singer and Hollywood star, invited them to visit San Miguel de Allende. They accepted the invitation and were captivated by the town upon arriving in February 1937.

In 1938, Dickinson became the director of the Escuela Universitaria de Bellas Artes. However, his work was cut short by World War II. From 1942 to 1945, he returned to the United States to serve in Naval Intelligence and later in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA.

After the war, Dickinson returned to San Miguel de Allende. He used his connections to enable veterans to attend the art school on the GI Bill, which funded free education for war veterans. News quickly spread about this new artist’s haven in the mountains of Mexico.

The GI Bill’s role in reviving San Miguel de Allende

Stories in Chicago newspapers and other publications began to feature San Miguel de Allende as a destination for veterans looking to study art, live affordably, and enjoy life. Following a glowing feature in the January 1948 issue of Life magazine, over 6,000 veterans applied to enroll, turning San Miguel into a “G.I. Paradise.” This influx of new students and visitors brought much-needed income to local businesses. The town began to flourish with a renewed energy centered around the arts.

However, trouble arose when a dispute over funding between the school’s manager and newly arrived Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros led to a walkout by students and faculty, with Dickinson’s support. In 1946, the Ministry of Education of the State of Guanajuato took over the Bellas Artes school, which now functions as the government-run Centro Cultural Ignacio Ramírez “El Nigromante”.

Holding on to the vision by founding the Instituto Allende

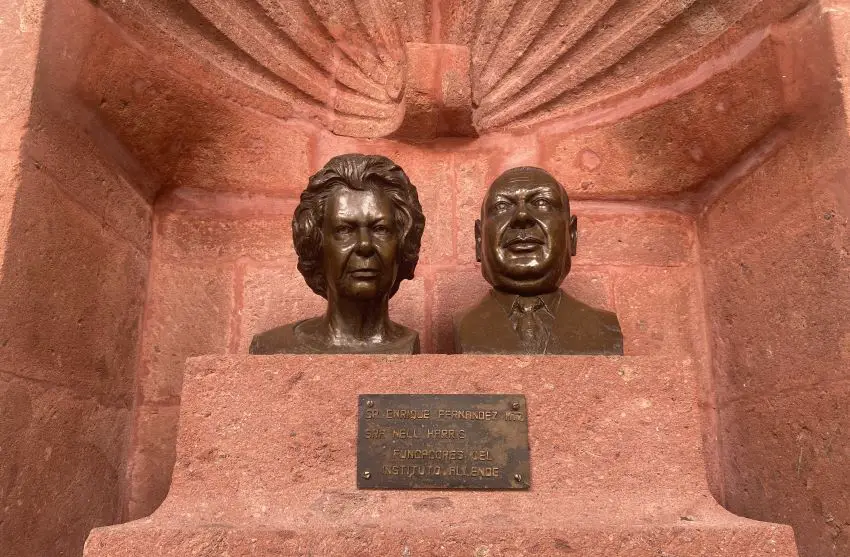

Despite this setback, the vision for a world-class art school in San Miguel de Allende did not fade. In 1951, Cossio invited Stirling Dickinson, Enrique Fernández Martínez (former governor of Guanajuato) and his wife, Nell Harris, to found Instituto Allende at Don Manuel Tomás de la Canal’s abandoned manor house.

Rodolfo Fernández, long time president of the institute, reflected on those early days: “Cossio had grand ideas, Dickinson was a fantastic promoter, and my father had the political connections, but the school’s true success stems from my mother’s extraordinary administrative vision and talent.”

A thriving artistic hub

Instituto Allende became a cornerstone of San Miguel’s cultural life, attracting new residents and tourists drawn by its art programs. The town’s economy flourished with the arrival of expatriates, artists, and students eager to be part of its vibrant arts scene, affordable lifestyle, and welcoming international community.

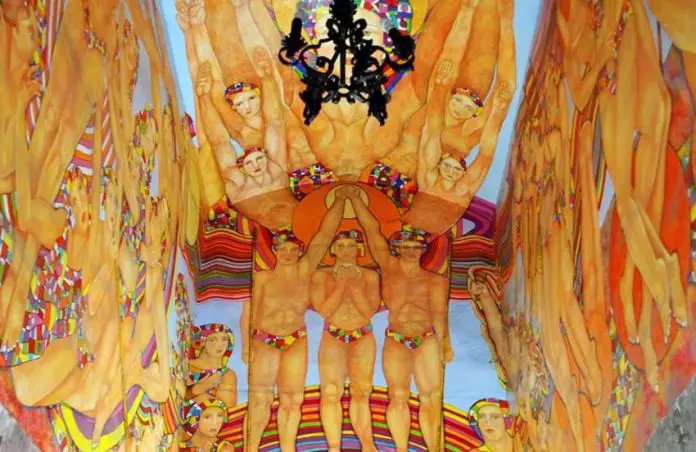

The high-quality courses offered at this private school continue to attract students from around the world. It is also a popular venue for a wide array of events, especially weddings, owing to its striking architecture featuring a central fountain, high arches and picturesque murals. The institute’s commitment to fostering creativity and education is as strong today as when it was first envisioned, strongly contributing to San Miguel de Allende’s worldwide fame as one of Mexico’s most treasured artistic destinations.

Sandra Gancz Kahan is a Mexican writer and translator based in San Miguel de Allende who specializes in mental health and humanitarian aid. She believes in the power of language to foster compassion and understanding across cultures. She can be reached at: sandragancz@gmail.com