Mexico’s agricultural landscape is undergoing a profound transformation. The rise of Protected Agriculture (PA) — including greenhouses, shade houses and plastic tunnels — has turned what was once a niche segment into a booming industry. Today, Mexico is a leading year-round supplier of high-value fruits and vegetables, primarily serving North American markets.

This article explores the scale, location, financial dynamics and technological innovations driving the Mexican protected horticulture sector forward.

The scale of Mexico’s protected agriculture boom

The growth of protected agriculture has been remarkable over the last two decades, fueled by export demand, government incentives, and modern production technology.

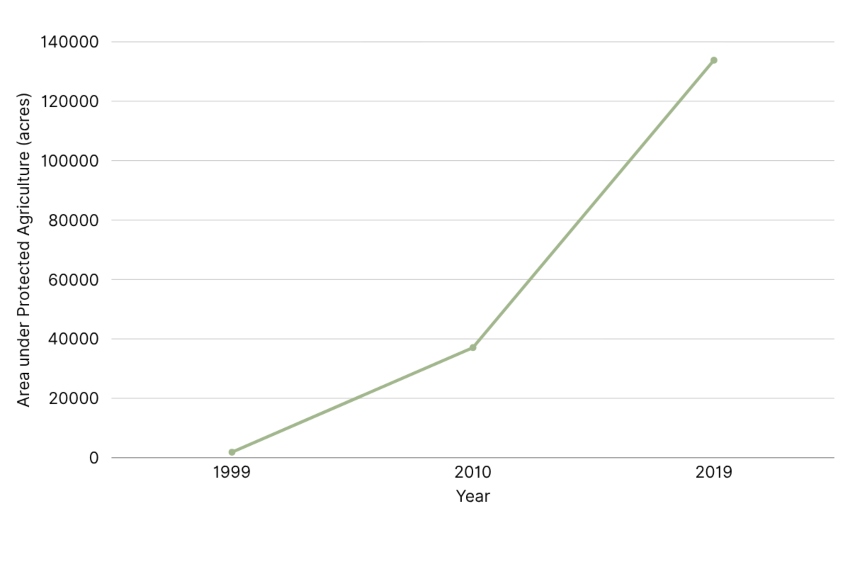

From 1999 to 2019, the area dedicated to protected agriculture skyrocketed:

- 1999: 1,853 acres (750 hectares, or ha)

- 2010: 37,065 acres (15,000 ha)

- 2019: 133,808 acres (54,150 ha)

The Mexican Association of Protected Horticulture (AMHPAC) manages roughly 23,107 acres (9,351 ha) of protected structures across 24 states. AMHPAC members have been expanding at an average of 3,707 acres (1,500 ha) annually, historically supported by government subsidies totaling 7 billion pesos (US $550 million) between 2001 and 2018.

Financial and productivity advantages

While investment costs are high, returns in protected agriculture are exceptional:

In 2018, protected agriculture accounted for only 2% of Mexico’s fruit and vegetable acreage but generated 17% of sector revenue. Controlled environments boost yields, delivering productivity up to seven times higher than open-field farming.

Production cycles extend from 12–15 weeks in open fields to 38–40 weeks under protection, enabling year-round harvests. This combination of high efficiency and longer production cycles makes protected agriculture an attractive option for investors and exporters.

Production hotspots and regional specialization

Mexico’s diverse geography shapes the type of protective structures used, creating regional specialization. Approximately 57% of Mexico’s total protected agriculture area is concentrated in Sinaloa, Jalisco, and Michoacán.

Northern/Northwestern states, such as Sinaloa (the leading tomato producer, contributing 22% of the national total) and Sonora, predominantly use shade houses. Their warmer climate and lower rainfall make this cheaper structure suitable for pest management and quality control.

The Central Highlands (the Bajío region), including Jalisco, Michoacán, Querétaro, Guanajuato and San Luis Potosí, have adopted greenhouses and plastic tunnels. Their altitude and lower temperatures necessitate the use of plastic coverings to regulate the climate and extend the growing season, allowing for stable, year-round production.

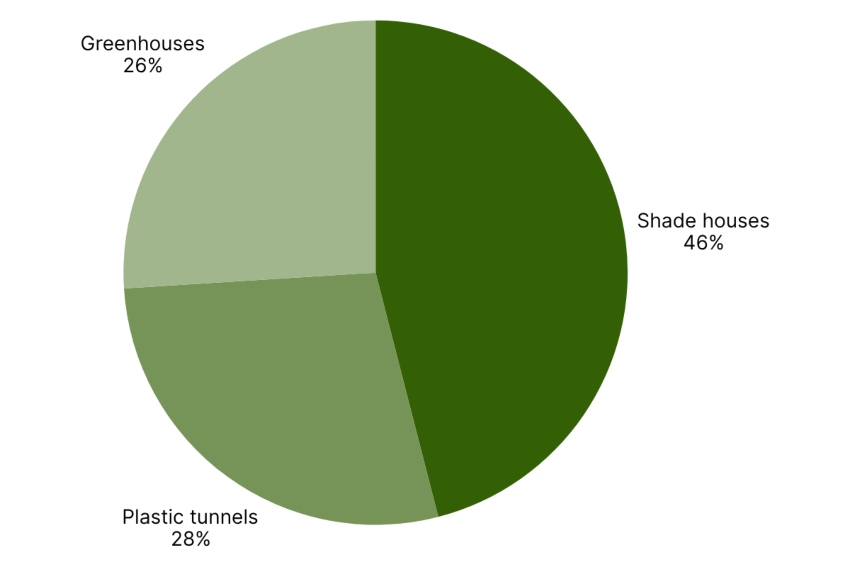

In 2019, protected agriculture areas were composed of 46% shade houses, 28% plastic tunnels and 26% greenhouses.

What Mexico grows

In Mexico’s protected agriculture sector, the vast majority of production — over 96% — is dedicated to high-value fruits and vegetables for export. The industry focuses on crops that offer strong returns on investment and meet the strict quality standards of international markets. The leading greenhouse crops produced (by AMHPAC members, rather than small-scale producers) are tomatoes (66%), peppers (18%) and cucumbers (15%), with berry production rising.

Tomatoes are a cornerstone crop, with approximately 67%-70% of total national production occurring in protected structures. Total national tomato production (protected and open field) reached an estimated 3.3 million metric tons in 2024. This has made Mexico the dominant supplier in the U.S. import market; in 2023, 88% of all greenhouse-grown tomatoes sold in the U.S. originated from Mexico.

Peppers and cucumbers, meanwhile are key high-yield exports. Bell pepper production in a high-tech hydroponic greenhouse averages between 28 and 30 kilograms per square meter. Along with cucumbers, they benefit significantly from Mexico’s proximity to the U.S. and Canada, given their short shelf life. The national output of green chile peppers was approximately 612,000 metric tons.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the production of high-value berries (strawberries, raspberries and blueberries) is one of the fastest-growing segments, leveraging protected environments to produce higher-quality products and making them a major U.S. export.

Export orientation: Supplying North America

The Mexican protected agriculture sector is a heavily export-driven model that leverages its climate to fill the winter market window in other countries.

An estimated 78% of all vegetables produced under protected agriculture are exported to the United States, with an additional 5% destined for Canada. The U.S. heavily relies on Mexican greenhouse produce, importing 1.82 million metric tons of Mexican tomatoes in 2023, valued at US $2.7 billion, which accounts for approximately 93% of Mexico’s total tomato exports.

This success has led to long-standing political friction. The industry has been combating the threat of tariffs from U.S. growers since 1996, with current tariffs standing at nearly 21% on Mexican tomatoes.

Domestic consumption is primarily a residual market. The highest-quality produce is channeled into the high-paying export market first, and the remaining supply is allocated to domestic markets.

Challenges and the push for sustainability

The need to mitigate risk and increase efficiency is driving the industry toward high-tech, climate-smart agriculture:

Resource scarcity

Drought and water scarcity are the most pressing environmental challenges, particularly in the northern irrigated regions. The industry faces intense pressure as agriculture is the largest water consumer and a major contributor to water pollution via nitrogen fertilizer runoff into aquifers and rivers.

The industry is responding to the challenge by utilizing advanced hydroponics and irrigation systems, which significantly increase water-use efficiency. AMHPAC has initiated a project to formally measure the sector’s water footprint in 2024 to diagnose usage and improve efficiency.

Labor and costs

The shortage of skilled labor and rising labor costs are pressing challenges. Qualified agricultural workers are increasingly migrating to the U.S. and Canada, making recruitment expensive and limited. This necessitates the adoption of automation and robotics to maintain productivity.

The industry, through organizations like AMHPAC, is focusing on improving working conditions, social responsibility and training to stabilize its workforce. Protected agriculture generated around 110,000 permanent jobs and 120,000 seasonal positions across the sector in 2024, according to the Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development (SADER).

Pests and diseases

New and virulent pathogens, such as the Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV), pose a threat, causing substantial economic losses and accelerating the need for investment in disease-resistant varieties and strict biosafety measures.

Economic pressure

The recent strength of the Mexican peso against the U.S. dollar has slowed growth over the past two years, as it makes Mexican exports less competitive in cost.

Clean energy transition and its impact on protected agriculture

Mexico’s national renewable energy strategy is increasingly shaping the future of its agricultural sector. The government has set an ambitious target of raising the share of renewable energy from 18% in 2023 to 45% by 2030, fueled by investments in solar, wind and energy storage. This clean energy transition is expected to reduce electricity costs and improve reliability, benefiting energy-intensive industries like protected horticulture.

With some of the world’s best solar conditions, Mexican producers are well-positioned to adopt on-site solar systems and participate in distributed generation schemes. Here are the key figures:

- Solar photovoltaic potential: 24.9 GW

- Wind potential: 3.7 GW

- Conventional geothermal potential: 2.5 GW

- Hydropower capacity: 1.2 GW

Much of Northern and Central Mexico, as well as the Baja California Peninsula, enjoys excellent solar conditions, with daily yields greater than 4.5 kWh/kWp (an energy output efficiency ratio), making it ideal for greenhouse operations. Many large-scale growers have already installed photovoltaic panels and solar-powered irrigation pumps, offsetting the high energy costs of heating, cooling and automated fertigation.

In addition, Mexico’s 2025 grid code requires new solar and wind installations to integrate battery storage equal to at least 30% of their capacity, ensuring grid stability — a critical factor for agricultural operations that demand consistent electricity.

Trends in growth and diversification

The industry is transitioning from basic protection structures to high-tech, climate-smart agriculture (CSA).

The Mexican vertical farming market is set for explosive growth, projected at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 16.66% (2025–2030). This signals a shift to ultra-efficient indoor production. Hydroponics is the dominant technique (64.1% market share). While lighting held the largest component sales share in 2024 (45.9%), sensors are forecast to be the fastest-growing component (17.8% CAGR), indicating a greater reliance on automated, data-driven climate control systems.

Mexico’s capacity for organic production is also expanding, with exports such as avocados, berries and tomatoes becoming a significant component of trade.

AMHPAC is actively working to establish phytosanitary protocols to target Asian markets, such as Japan, Singapore and South Korea, regions that offer premium prices for high-quality Mexican products. A key strategic goal is to establish facilities for lycopene extraction from non-export-quality tomatoes, which will be sold to international buyers. This pioneering bioeconomy model converts agricultural waste into a high-value industrial product.

Mexico’s protected agriculture industry has matured into a highly specialized, globally essential sector. While facing challenges in labor, water and disease management, continued technological investment, innovation and strategic geographic advantage ensure its ongoing growth. As a year-round supplier of high-value produce, the sector remains a cornerstone of Mexico’s agricultural exports and a model for modern, climate-smart horticulture.

Irena Vélez is a journalist at Wikifarmer.com, based in Seville, Spain. She holds a Bachelor’s in Journalism Honours from Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, and has a background in agricultural reporting. She writes research-based articles on sustainable farming, crop management and rural entrepreneurship, helping make agricultural knowledge accessible to farmers worldwide.

For readers looking to dive deeper into the protected agriculture sector, Wikifarmer offers expert insights, market data, and crop trends. Wikifarmer empowers farmers, agribusiness professionals, and industry observers through four key pillars: the Wikifarmer Marketplace, connecting producers with buyers around the world; the Wikifarmer Library, a free knowledge hub with thousands of expert-authored articles on crops, technologies and best practices; the Wikifarmer Academy, offering online courses with certifications to enhance agricultural skills; and Wikifarmer Price Insights, providing real-time market intelligence on key commodities. By combining practical expertise with up-to-date data, Wikifarmer helps stakeholders navigate the complexities of modern agriculture, making it an essential resource for anyone interested in Mexico’s booming greenhouse and horticulture industry.