One beauty of Mexico is its extraordinary artisans, Michoacán’s artisans topping the list. The many villages dotting the state are famous for their unique crafts.

We decided to explore some on a recent trip to the state capital of Morelia. Our tour guide, Rueben Reyes, took us to several places in our quest to find treasures for my home in Zihuatanejo. Among those places were the village of Cuanajo, which specializes in beautiful hand-carved, hand-painted furniture — from rustic pine designs to the more elaborate and expensive ones made from parota wood. We also visited Capula, just a short drive away, which specializes in Catrinas of all sizes.

One standout for me was Santa Clara del Cobre, best known as the town of coppersmiths.

A designated Magical Town (Pueblo Mágico) since 2010, Santa Clara del Cobre is located 18 kilometers from Pátzcuaro and 79 kilometers from Morelia, the state capital.

The Purépecha people have been working copper here since the pre-Hispanic era, which led to the town’s dominance in copper crafts well into the 19th century. After nearly dying out by the mid-20th century, the art has been revived by tourism, and today, 82% of the town’s population makes copper items, and over 250 registered workshops in and around the city process 450 tons of copper each year.

Each year, at the end of July, the town holds an artisan fair showcasing the many artists and studios, the National Copper Fair, also choosing a queen to preside over the festivities.

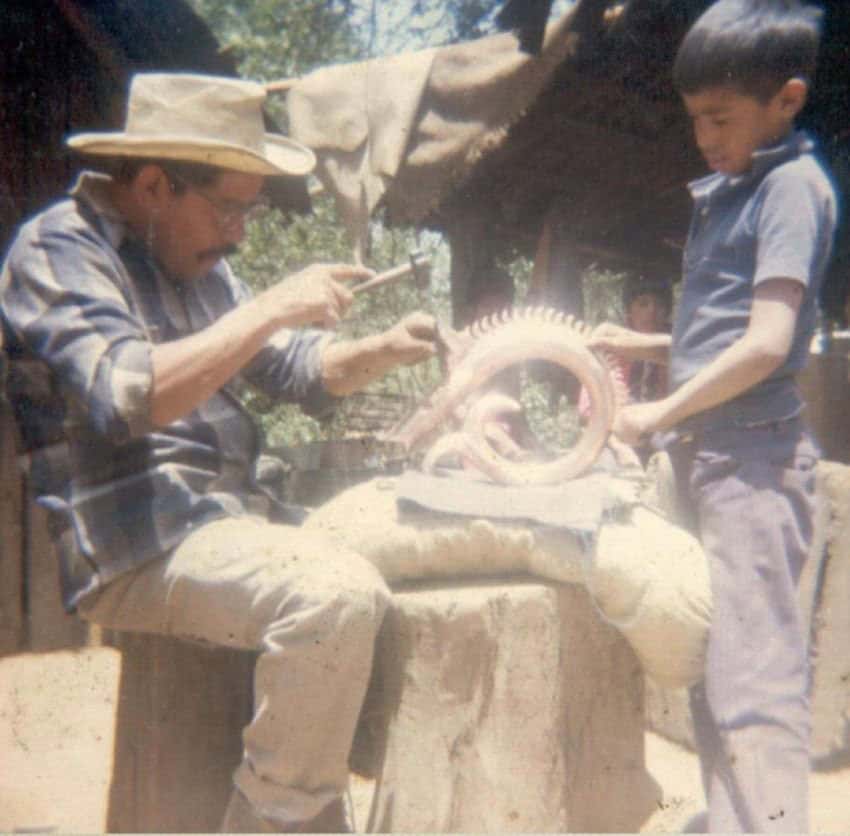

The book “Grandes Maestros del Arte Popular Mexicano” featured copper artist Jesús Pérez Ornelas, considered one of the most outstanding craftsmen of his time. Pérez, who passed away nearly 10 years ago, was most famous for his intricate engraving, the beauty of his designs and the quality of his finishings.

He worked well into his 70s in Mexico and abroad and was dedicated to his craft and to teaching others in Santa Clara del Cobre. Like his father before him, Pérez, also a gifted storyteller, passed his enormous skill onto his three sons, Ambrosio, Jose Sagrario and Napoleón Pérez Pamatz.

I was fortunate to visit the well-ventilated, open-roofed shop where the magic happens, located adjacent to the family home, typical of most local coppersmiths here. I spoke to Jesús’ youngest son, Napoleón, who explained the fascinating steps in making this truly intricate art.

“We learned how to make copper at our father’s knee from the time we were six, seven years old,” he said. “Our first job was to fan the fires using huge billows called bechizo. The boy who maintains the fire is known as a zorillo, or ‘little fox.’ Almost all coppersmiths begin the trade this way.”

He pointed to the tools that surrounded him. They included anvils, picks of various sizes, awls, chisels, hammers and pliers. “Then we learn to use these.”

To demonstrate, Napoleón heated a piece of metal until the copper was red-hot and removed it from the coals and ash with large tongs. Then, with a hammer and precise, even blows, he struck the copper until it began to take shape. Occasionally, he reheated the piece and continued to hammer it into a small bowl.

“Next, we will polish the piece,” he said.

Napoleón demonstrated this by rubbing a cloth onto the copper.

“And then we etch in intricate designs, like flowers, animals or anything the client wants. My family is known for these designs made famous by my father,” he said. “The final step is a sulfuric acid bath rubbed with steel wool dipped in soap and water, followed by another polishing.”

Seeing the passion the family poured into every piece, and the generational history of the family itself, I was hopeful I would find something to take home with me. However, unlike the shops that line downtown Santa Clara — which is well worth the stroll — there were more pieces in various stages of design than there were finished works.

I then spotted a stunningly beautiful copper bowl on a workbench set to one side. When I learned it was for sale (4,000 pesos), I promptly bought it. It was one of Napoleón’s.

While I waited, he signed it for me, and it now sits proudly on a credenza in my living room, where I will treasure it for years to come.

The writer divides her time between Canada and Zihuatanejo.