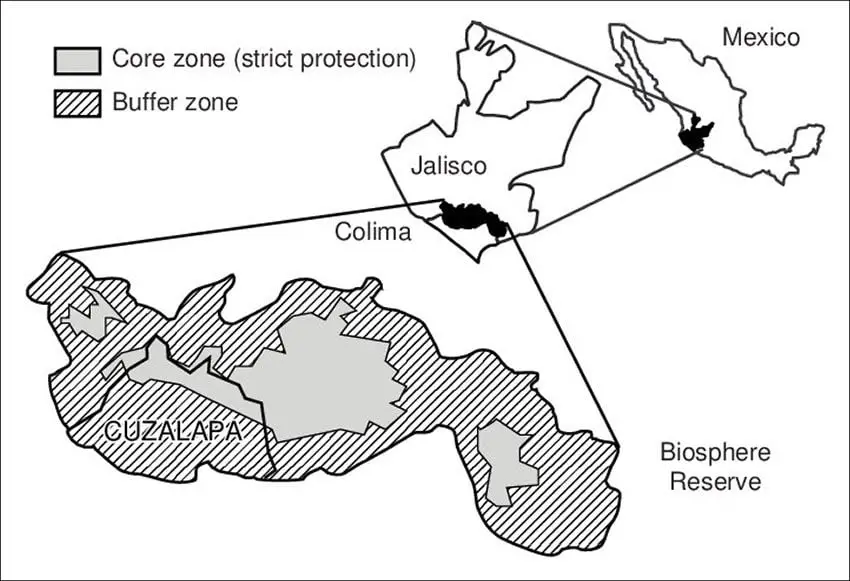

The Sierra de Manantlán Biosphere Reserve, established by UNESCO in 1988, lies along the border of the Mexican states of Jalisco and Colima and includes cloud forests and deciduous, mesophytic and tropical forests within its boundaries.

It also includes hundreds of caves, almost all of them vertical pits.

Ninety-four of these caves are described in the book Las Cavernas de Cerro Grande by Carlos Lazcano, but only one of them was found to contain a notable number of formations such as stalactites and stalagmites. That cave, La Cueva de los Monos, is considered by some to be Jalisco’s most beautiful cave, but hard to reach.

This is the cave we had come to visit and below are a few notes on our expedition:

It’s 7:00am at Rancho El Zapote. The air is full of early-morning sounds. Loudest of all are the roosters that live only meters from my tent and have been trying to wake me up since 4:00am. Then come the chickens, a very large pig and dozens of loudly mooing cows, one of which wears a clanking bell, indicating that she is the leader of the herd. I guess it’s time to get out of my sleeping bag and into my caving pants.

Today we are going to visit La Cueva de los Monos (Cave of the Figurines), which can only be reached after a long, hard climb up a steep mountainside above the little town of Toxin, which is located 37 kilometers northwest of Colima city. The cave is so named, I understand, because local people claim they found artifacts inside.

Our group obviously considered a good breakfast the key to good caving, so it wasn’t until 10:20 that we finally headed up a north-trending trail which at first struck me as very friendly, after all the horror stories I had been told about the previous visit to this cave: “That climb was a killer,” said Mario Guerrero, leader of both our present trip and the preceding one, “because it was the hottest week of May, which is the hottest month of the year, and we hadn’t brought along nearly enough water.”

Now we were enjoying the relatively cool weather of November and we gained several hundred meters of altitude in a matter of minutes. The higher we rose, the more big, white, rocky outcrops we found along the way. “This is karst,” said a member of our expedition, Spanish geologist Isidoro Ortiz, pointing out the prickly surface, weathered by the rain, indicating that we were inside a calcite zone where beautiful caves were likely to be found.

“At this rate we’ll reach the cave in nothing flat,” I thought, but at that very moment our friendly trail came to an end at the edge of a cornfield. “¡Chin!” said Mario. “No sign of the trail anymore, but all we have to do is keep going north and we’re bound to find the cave.”

Well, the cornfield into which we plunged also happened to be home to billions of well-developed, ripe-for-traveling huizapoles (very prickly burrs) with which we were soon covered head to foot.

At last we got through the cursed cornfield and stopped under a huge ficus tree to pick the burrs off one another. After removing a million or so huizapoles from our clothing, we pushed our way into thick maleza (bush) higher than our heads. “¡Ay ay ay, uña de gato!” I heard someone yell up ahead. This is cat’s claw, just about the nastiest form of thorn you can find anywhere, as it is designed to grab you as you pass by and then tear your skin to shreds. We now had to proceed with great caution.

It was about this point that our guide, Noé, son of our host at Rancho el Zapote, was forced to start swinging a machete in order to advance, further reducing our forward speed to that of a procession of turtles.

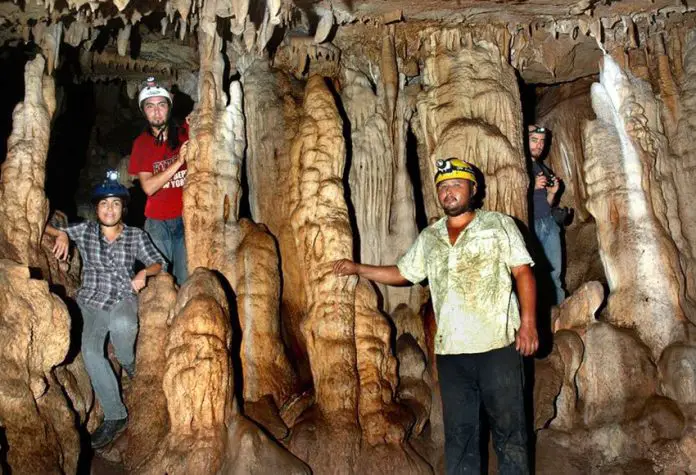

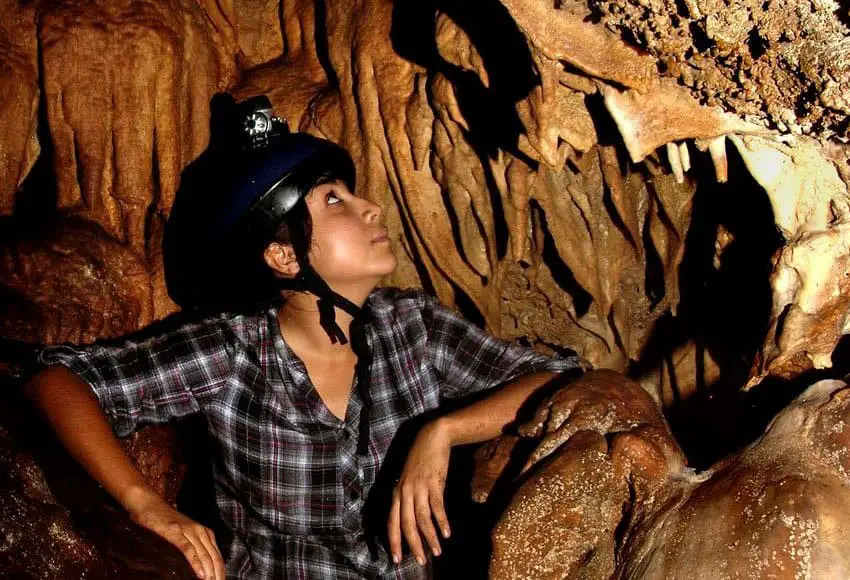

At last, dripping with sweat, well scratched by cat’s claw and covered with a new set of burrs, we arrived at the cave entrance. A crawl of four meters took us into a room so thickly decorated with stalactites, stalagmites and draperies that several hours of photography went by in what seemed like minutes. By the time the last of us crawled out into the sunlight, everyone else in the party was either sleeping or eating.

Well, the route that we had followed to get to the cave had been so unpleasant that we all breathed a sigh of relief when our guide Noé suggested we take a more direct and hopefully easier route back down the mountain.

And easier it was, at the beginning, with very little vegetation between well-separated outcrops of limestone. However, as the hillside grew steeper and the bush grew thicker, our old friends the burrs and cat’s claw reappeared and once again the machete was absolutely necessary for making the slightest progress.

Following this route, however, we had a whole new problem to deal with: the limestone had turned into heaps of sharply pointed rocky rubble which, like chunks of lava, were delicately piled one atop the other, offering the most treacherous footing imaginable.

We soon reached the point where we had only two hours left to get back to our truck before nightfall and at least a kilometer of nearly impenetrable bush to hack our way through. To make things worse, one member of our group, Ivan the biologist, was under attack from some sort of bug and suffering from all those unspeakable intestinal terrors usually reserved only for foreigners in Mexico.

At last we tore ourselves away from that enticing hole and once again resumed our grim assault on the unforgiving mountainside. Dripping with sweat, disentangling ourselves from thorn bushes and dreaded cat’s claw, scratching some new, mysterious red welts which had suddenly appeared on our skin, and teetering on unstable chunks of prickly rock, we inched our way downward.

Several times we were on the brink of mutiny: “It will take us a year to get down this way; we have to go back up to the cave and return the way we came,” cried some voices.

[soliloquy id="67361"]

Noé, however, kept chopping away calmly and, lo and behold, one hour before sunset, we spotted the infamous huizapol cornfield! But now, oh how friendly and inviting it looked!

To make a long story short, we were soon back on our beloved trail and reached our truck with several minutes of daylight to spare. Was it worth it? Yes, indeed! In all my 33 years of exploring Jalisco’s caves, I haven’t seen another with so many beautiful decorations. So, wearing proper burr-and-thorn-proof clothes, I’d be ready to go back anytime!

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.