For jazz fanatics in the United State and around the world there are dozens of small independent labels where you can find new and experimental jazz – Porter Records, Sunnyside and Tzadik just to name a few. But here in Mexico you won’t find a single individual label dedicated to solely jazz, that is of course, until now.

“I was born into a family that loved art,” says Juan Pablo Aispuro, founder of Pitayo Music. “Both my parents are architects — not musicians at all — but my grandfather on my mother’s side was. This is his piano.” He points to the nearby Steinway.

“He had a bolero trio with his brothers. So at every party he would say to me ‘grab the maracas,’ ‘grab the guitar.’ He taught how to play any instrument.”

Along the walls surrounding Aispuro are other instruments – bows for the cello, an upright bass. A few guitars. Gourds covered in beads, mini-wind chimes, a tiny instrument that sounds like rain when turned upside down.

The studio is small, cozy and warm on this unusually cold day in February in Mexico City. I sip my instant coffee and Juan Pablo looks off dreamily as he describes his love affair with music.

“Instead of soccer, I played in the orchestra,” he says with a grin. First cello in fact in the Universidad Panamericana Chamber Orchestra when he was a young teenager. He attended the Colegio Cedros as a grade-schooler and was on the path to becoming a great musician long before the beard growing on his face had began to sprout.

For high school he transferred to the Tec de Monterrey and upon graduating was set on studying architecture. That is, until his architect mother pulled him aside and essentially said, “What, are you crazy? Your thing is music.”

So he started to work at a local recording studio instead, and for the first time came face to face with the music that would change his life.

“The studio is where I heard jazz for the first time. I didn’t know anything about it before that. I didn’t even know what a standard was. And I thought to myself, ‘I have to learn how to play this, I have to learn to understand it.’”

So Aispuro decided on Paris, one of the great jazz epicenters in Europe, and studied at the American School for Modern Music for four years. When he finished his studies he did something that Mexican jazz musicians from the generations previous didn’t normally do – he came back.

And not just Aispuro. According to him, a whole generation of young musicians came back to Mexico, and when he arrived eight years ago after his four-year hiatus he realized there was a lot more going on than he thought.

“I think part of why I left is because I didn’t know about the jazz scene here. It existed but I didn’t know that. I knew a few names, but in reality I knew very little. There was no promotion, no publicity, no radio stations, and the typical jazz musician is someone who doesn’t care, they’re not out there looking to give interviews … they just want to play music.”

“I think something that happens in jazz is that there is a lot of auto-consumption among musicians. Me, as a musician I know everything that other people are doing, but non-musicians don’t. It’s a type of music that doesn’t leave the stage.”

In order for Mexican jazz musicians to get noticed they had to play abroad; in order to get a contract they had to be signed by some international label. There were no contests, no festivals. And even though the digital age was most definitely upon them, musicians weren’t uploading their work to platforms like cdbaby or Spotify or Soundcloud. No one could hear their songs unless they were sitting in front of the stage.

So Aispuro started asking musicians to come and play jam sessions at his studio and he started to record the tracks. He found he had a knack for producing, and other musicians respected him because he was a musician himself. The first albums he put out were compilations of those early sessions called, Sesions del Casa de Arbol, wide-ranging and wandering tracks that demonstrate the breadth of styles that can be found among Mexican jazz musicians.

“I realized that there was this big jazz scene in Mexico City that was experiencing a boom, but it wasn’t accessible. Once I was inside and realized there were these great musicians, I thought, ‘I think that it’s my job, and something I want to do, to show the world what is going on,’ and that’s why I started with the compilations. It’s much more difficult to make your own album and get a lot of notice than if you have an album with 20 different musicians on it.”

And there was a distinctiveness to the Mexican jazz scene that Aispuro hadn’t experienced in Paris.

“Here in Mexico you can play four or five nights a week. In Paris you play once every two months. And it’s more a thing where I get some dates and then I see who I can play with, instead of looking for dates with my specific project. So maybe I play four times a week and none of those are with my band. Each time I play with someone different and it’s really enriching to the scene, because everyone plays with everyone and you improve your playing. In other places that only happens in jam sessions.”

Musicians get to know each other well and because there is a high demand and limited offer, there are a lot more opportunities for them to play in Mexico City, in Guadalajara, and in Puebla than in Copenhagen or London. This generation of young musicians, adds Aispuro, is making jazz into something that resists a singular category.

“There are a lot of young musicians that see themselves as ‘Mexican jazz musicians,’ to the point that what most of them play isn’t swing, isn’t American jazz. We can call it jazz because it has a lot of similarities to jazz and improvisation, but personally, I’m not really comfortable calling everything ‘jazz’ anymore, because I think it has cultural connotations. I think we are developing a kind of contemporary Mexican music.”

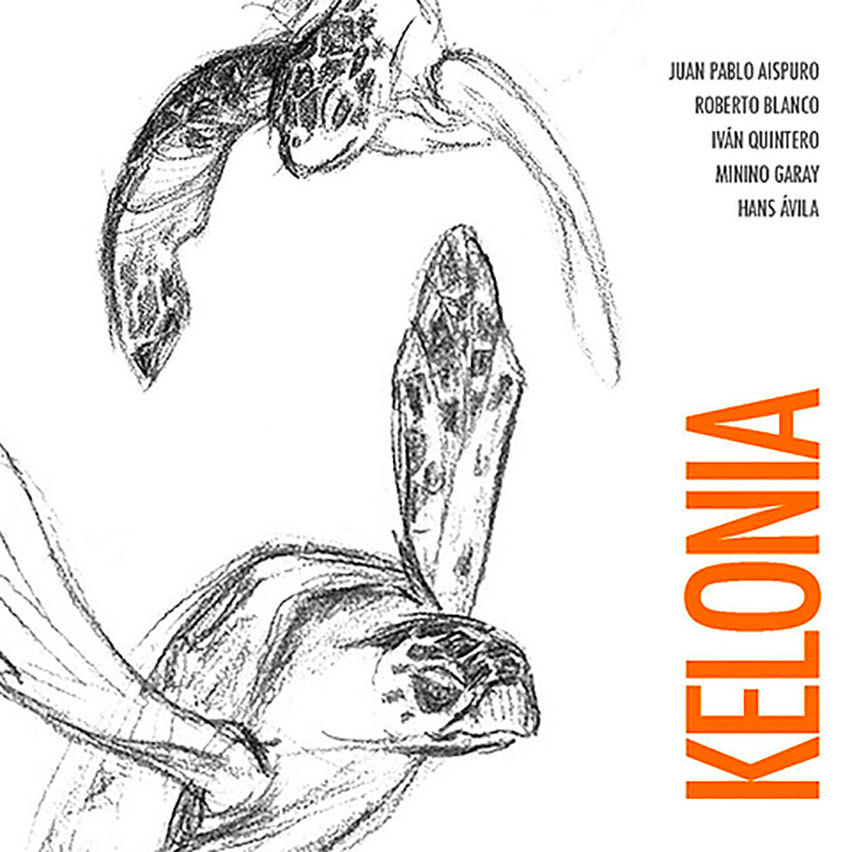

In 2016 Aispuro came out with his first non-compilation album, Chilacantongo, produced for saxophonist Diego Franco from Guadalajara. The record is an audio reminiscence of the young artist’s life in the city and his talent is apparent from track one. This album was the birth of Pitayo Music (in Spanish) as a serious label, which would now be producing artists (they currently have four) as well as fomenting jazz culture in the city.

“For me it’s really important that the new generations know that there’s this incredible scene they can join and that that scene’s not in New York or L.A., it’s here or in Jalapa or Puebla and its theirs. That’s really important, that they know that they can create music within their country and be part of a scene here.”

It also important to Aispuro to have a local label that can provide access to the city’s music for players and jazz lovers. Instead of having to go outside their country, musicians can produce an album right here at home.

“I want it to be like Blue Note,” he says, “like you see it and think ‘I don’t even know who this is, but Blue Note is always good so I’m going to buy it.’”

With a true musician’s heart, Aispuro says he hopes that people copy his ideas and start all kinds of small local labels and studios.

“What better way to enrich the jazz scene?” he asks.

• Listen to an online solo piano concert by Alex Mercado webcast from the Pitayo Music studio on Wednesday, March 25 at 9:00 p.m. CT. The cost is US $5.00.

The author is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily and lives in Mexico City.