Want to know what casual racism in Mexico looks like? It’s pretty simple. When my Mexican friends met my ex-husband, they all said the same thing: “I could not believe that was your husband.”

It’s a confession that never comes until after at least a year of friendship. And it only comes from Mexicans.

The reason? My ex-husband is very dark-skinned. And for most Mexicans to consider you good-looking if you’re very dark-skinned, you need some other redeeming qualities. A supermodel’s body, perhaps, or piercing green eyes. The visual trappings of wealth are also an immense help, as they are anywhere.

To me, of course, he was very good-looking. And I wasn’t alone in my opinion. When we traveled to the States, my U.S. friends would pull me aside: “Wow, he’s cute!” Finally, some people who understood. They saw what I saw!

When I was talking to some women a few weeks ago for my article on reluctant immigrants, this was a theme that came up among those who’d “returned” to Mexico with their husbands. Many were repeatedly faced with confused questions about why on earth they were willing to come. An incredulous “¿A poco te gustan los morenos?” (So you really like brown guys?) was a common question.

Um. Yes? And also, what is wrong with you?

Racism a la mexicana

Modern racism in Mexico is a little hard to compare to the racism we find north of the border. It is just as real here as it is there and in the rest of the world, of course. But it’s a different flavor, mixed up to a greater degree here in social class.

The North American roots are the same: Europeans kidnapped Africans and brought them to the Americas to force them into slave labor. They ran the show, so society, including beauty standards, was set up in their image. To this day, the more European-looking you are, the better-looking many consider you to be.

One major difference, however, stems from the fact that Indigenous peoples were very nearly wiped out in what’s now the US and the ones that survived were siloed off. In Mexico, however — to put it politely — the Europeans “married” them instead. The ones that survived their initial onslaught, anyway. Were the European boats filled with couples and families or with single men? The answer to that question can give you a lot of clues into how the subsequent societies developed.

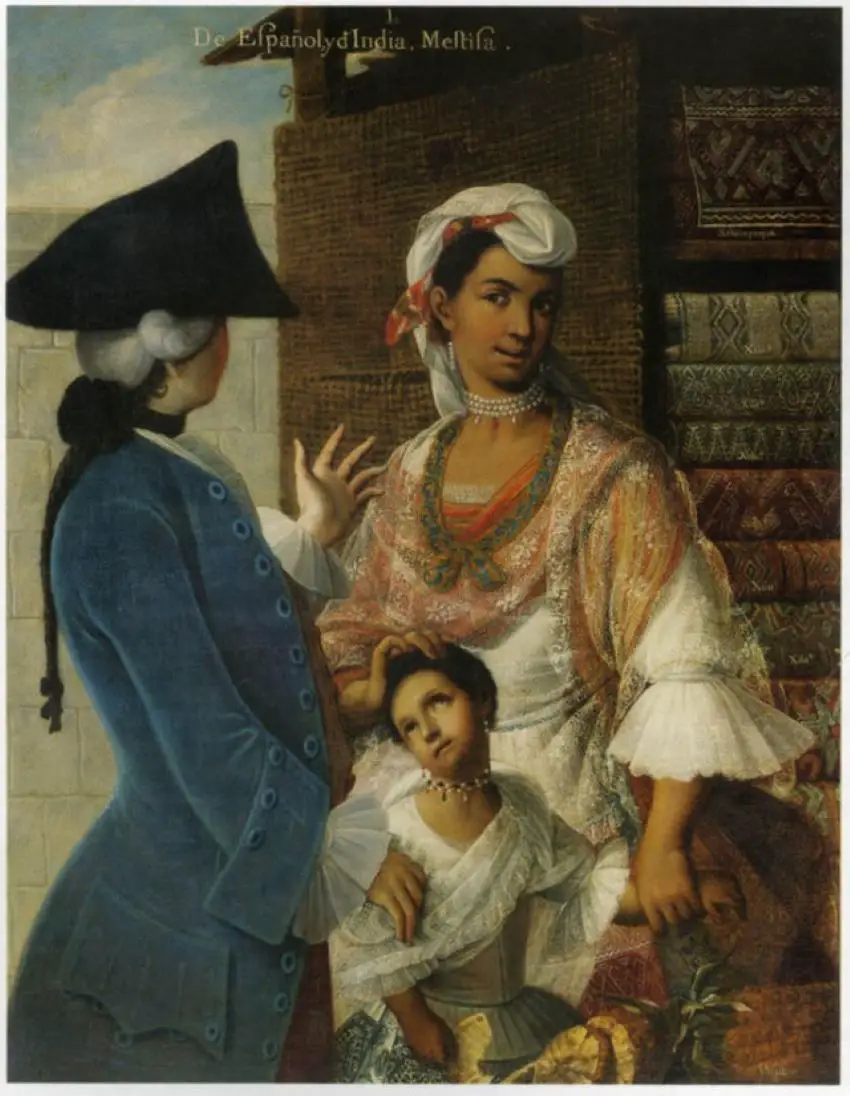

There was initially an elaborate “blood-based” caste system here that eventually gave way to “mestizaje” (mixing, I guess?). And as a mestizo country, differences in skin color became more economic indicators than “racial” ones. Those of Spanish descent could afford to give their kids a higher leg up because they of course placed themselves at the top of the social ladder when they took over. And while a few pockets of people of African-descent remain, most joined the mestizo population. Slavery, by the way, was outlawed in Mexico decades before it was in the States. In fact, that was one of the main roots of the fight over Texas, something you won’t ever learn in Texas History.

So, even today, the Indigenous continue to find themselves at the bottom of the barrel. This isn’t because they are brown; it’s because they still belong to ethnic groups that are not part of the “mainstream.” They are the poorest and most isolated groups in Mexico and the ones with the least access to quality education and modern services.

Here, preserving one’s Indigenous roots means not “modernizing.” And not modernizing in Mexico means you’re left behind, basically, to toil for those in charge. While some make a big deal about embracing Mexico’s indigenous roots, it’s notable that those who do so are noticeably far-removed from them in background and social class.

So racism, in Mexico, is more about one’s perceived social class and lack of education. And because different “races” didn’t stay siloed off from each other like Jim Crow laws and institutionalized discrimination caused people to be in the US, markers of distinct culture and language didn’t develop, either. There’s no Spanish version of the “Black vernacular,” for example.

Mexico’s no racial utopia; it’s simply divided up based more on social class and education.

Still, the legacy of colonialism means that, generally, the higher up you go in wealth, the whiter people get. The opposite is also true: the darker and more Indigenous-looking someone is, the greater the likelihood that they’re poor and have had very little access to quality education.

Living with the legacy

So, here we are. Like in the rest of the Americas, white people are grossly overrepresented in positions of power. Any group that forcefully takes over gets to run things and impose its own beauty standards, I suppose.

And that in turn gives us things like mostly white Mexican models, though most Mexicans are much darker-skinned. It gives us things like Mexican TV shows where most principal characters are white, while the only darker-skinned actors play servants. It gives us fetishes for “light eyes” and anything but black hair. It makes people joke that to marry someone whiter than you is to “mejorar la raza” (improve the race).

It gives us the fame of Luis Miguel. Yes, he’s a great singer and performer, but come on. Would he be Mexico’s heartthrob if he weren’t blonde? It gives us the “common wisdom” that men from Guadalajara are the most handsome. Spoiler alert, I’ve been there: they’re not more handsome, they’re just whiter and taller.

So when some Mexicans see white foreigners who, because of this legacy of colonialism, are considered to be at the top of the “good-looking people” list fall in love with those they themselves might write off as too average, they’re confused. Perhaps to them, it looks like Brad Pitt falling madly in love with Rosie O’Donnell. “You could have your pick, and that’s your choice? Really?”

No doubt more than a few assume we’re being taken advantage of too, used for our imagined millions. Casual racism works both ways, after all, even in Mexico.

This is not cool, but it is the reality. Foreigners anywhere are often “othered,” our motivations a mystery. I won’t pretend to know what minorities in the US feel, but being a closely-inspected “representative” of one’s culture is not always fun.

At least my partner gets me.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, https://sarahedevries.substack.com/.