There are only a few things that I remember about my 7th-grade Texas history class.

One is my teacher: a tall, somewhat portly man with a kind face who would get tears in his eyes every time he talked about Sam Houston, his hero. He was in his 60s, lived with and cared for his mother, and played the piano. Once he chuckled warmly, clearly charmed that I pronounced the word “sweat” as “sweet” when reading out loud from the textbook, which made me feel about 20% less embarrassed than I would have otherwise.

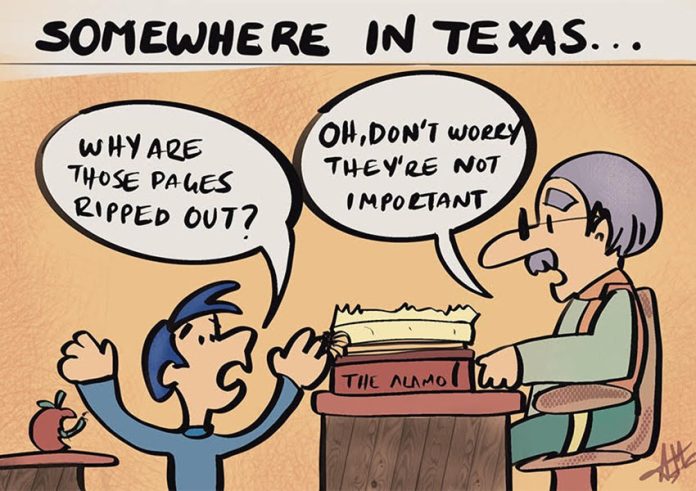

From the content of the class itself, I remember very little, except that the Mexicans were the bad guy aggressors, trying to block the inevitable flow of history toward freedom and independence.

I’m a much better student these days, much better at paying attention now that I’m no longer preoccupied with the boys in the class I think are cute (these classes really are wasted on the young).

And having just come back from Texas a few weeks ago with a borrowed book, “Forget the Alamo“ in hand, I’ve got my home state — the Lone Star state! — and all its peculiarities on my mind.

Texas is, after all, a state of mind. You also should not mess with it, I’m told, or tread on …someone, whatever that means; the “someone” is possibly a snake. Furthermore, one can go to Texas while the rest can go to hell, and naysayers are also invited to “come and take it — “it” being a stand-in for pretty much anything (these days, probably guns).

All of these charming phrases are available for purchase on T-shirts, mugs and beer cozies at a relatively new but already deeply-loved Texan institution, Buc-ee’s.

Texas even has some famous fans, most notably, Phil Collins. He could very well be the Alamo’s number-one fan, in fact, and has spent stupid amounts of money amassing one of the most impressive collections of Texas artifacts in the world. I know this fun fact because I read it out loud in a Texas Monthly article to my sister on one of our hours-long trips across our gigantic state.

But reading more deeply about my home state’s history has given way to some startling realizations. I always knew, I suppose, that the “heroes of Texas Independence” weren’t saints. Still, there are some important details that have made my eyebrows go way up.

Texas and Mexico have always had a contentious relationship. While there’s Mexican influence aplenty blended in with the overall Texas culture, it’s clear who’s in charge.

Mexican-ness in Texas has always been something separate, considered by most without Mexican heritage to be a tacked-on rather than homegrown feature. Tejanos, or at least tejano culture, are generally treated by the more powerful Texians as guests who’ve overstayed their visit but whom they’re too embarrassed to ask to leave since this home did once belong to them.

Spanish, the European language of the land preceding English, is merely an elective in school like it is everywhere else in the country. Also like the rest of the country, Texas has a difficult and fraught racial history to contend with, the effects of which can still be quite clearly seen today.

Well. As we all know, the winners write the history books.

And write them they did. I never understood, for example, that the whole motivation for Texas’ independence from Mexico was about preserving its right to keep slaves. Did you know that? According to Texas government records, there were about 5,000 slaves there by the time of the Texas Revolution in 1836, 30,000 by the annexation a decade later, and 182,566 by 1860 — more than 30% of the total state population.

Was I really just not paying attention in Texas history class, or was the mention of slavery merely a footnote, if that?

In case you don’t know it, here’s the story in a nutshell: Before any Europeans got to the Americas, it was, as we know, occupied. That meant little to the Europeans, of course, and Texas — as well as what currently makes up the southwest United States — was claimed for New Spain in 1690. When Mexicans gained independence from Spain in 1821 (a war that began in 1810), Texas became a part of the new nation.

For most of its early history as a Mexican territory, however, Texas was pretty sparsely populated by Mexicans or any other European-descended people, for that matter.

First of all, there were no Buc-ee’s back then — that’s minus 10 points right there. Plus, the combination of (rightly) aggressive Indigenous groups and oppressive heat made it the backwoods where no one was exactly dying to live.

Mexico had a hard time getting very many of its citizens to populate it, and with good reason: who wants to deal with heat, frequent attacks plus no Buc-ee’s?

All kinds of riffraff from the eastern U.S. were plenty willing, though, to take their chances on claiming a lot of land. Texas was attractive because you could get rich there. Alas, there was really only one way to do it: having slaves work your cotton fields.

So, quite a few gringos started moving in, most illegally. But since Mexico wasn’t able to get enough Mexicans to live there in the first place, it was a relatively easy immigration invasion to make. Before they realized it, Texas had a downright infestation on their hands of people who didn’t speak Spanish, weren’t Catholic and blithely ignored their laws.

The biggest problem, however, was that the newly independent Mexico was an abolitionist state; slavery was outlawed in 1829.

But without slavery, there was no reason to go to Texas in the first place, in the gringos’ minds, anyway. They found ways around the laws for a while with things they shouldn’t have been able to get away with, like saying they didn’t know about the laws because they didn’t speak Spanish — and later, classifying their slaves on paper as “servants.”

It got out of Mexico’s hands quickly, and by the time Santa Anna said, “enough is enough,” the weird wheels of history, complete with bizarre accidents that make it feel like fate, were already in motion.

In short, the invaders of Texas took over and made it their own, casting themselves as righteous heroes against their dictatorial Mexican aggressors. We all know what happened next, because here we are: the Mexican border no longer goes past the Rio Grande.

It’s been a couple hundred years, but the echoes of history are still bouncing off the walls, and the tension between Mexico and their smiling, blue-eyed guests will likely never completely disappear.

Under the circumstances, it’s honestly a wonder they’ve been so patient with us. Of course, they’re in no danger of being overrun by us now — we think.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com