Eusebio Francisco Kino is one of the most brilliant, great-hearted and colorful characters in the history of Mexico, but outside of Sonora he is perhaps somewhat forgotten.

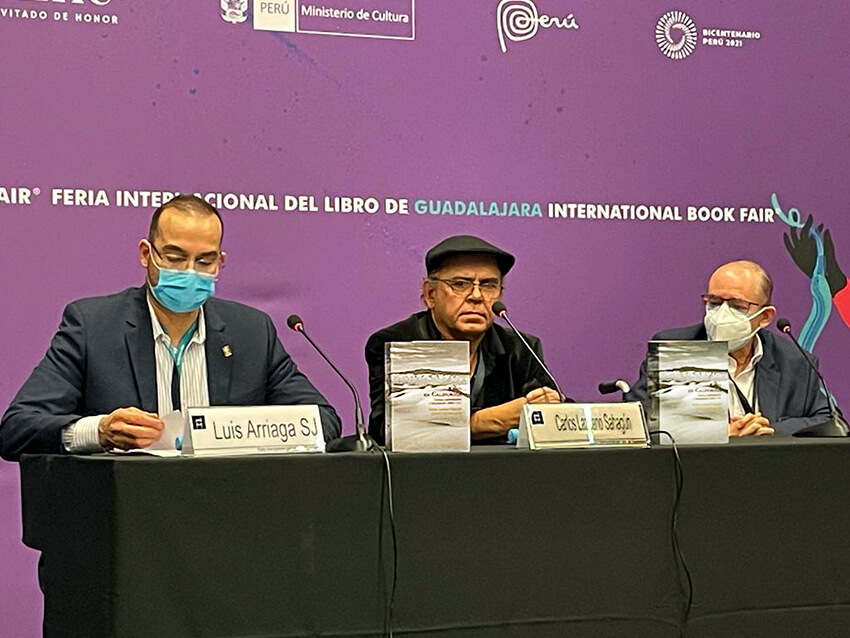

When I heard that historian Carlos Lazcano had just published a book over 1,000 pages long on Padre Kino, I must confess that I was surprised (in my ignorance) that he had found so much to say.

All I knew then was that the man Padre Kino had founded lots of missions while Padre Kino, the wine, was hardly worth one page of print, much less 1,000.

Lazcano’s tome, Kino en California, is coauthored by Gabriel Gómez Padilla.

“It contains 500 pages of Padre Kino’s writings and 500 pages of my own,” Lazcano says.

Now I was intrigued. Besides founding missions, Padre Kino had obviously spent a lot of time writing — but about what? And was it really so important that Lazcano had penned 500 pages of comments on it?

Naturally, all this drove me straight to Wikipedia. Here I found that Kino was born in Trent in 1645 as Eusebio Chini and that he was a missionary, geographer, explorer, cartographer and astronomer. Then follows much information on the founding of missions and, appropriately, only one line about the wine.

Beyond Wikipedia, I found many, many sources of information on Padre Kino. Out of them all, there slowly formed a most interesting story.

Kino joined the Jesuits with the hope that they’d send him to China, where the priest Matteo Ricci’s skills as a scientist had opened doors at the highest levels. Kino applied himself diligently to the study of cartography and other disciplines, but when his chance came, it seemed there was only one opening for China — and two contenders.

Both of them drew lots, and Kino’s read “Mexico.”

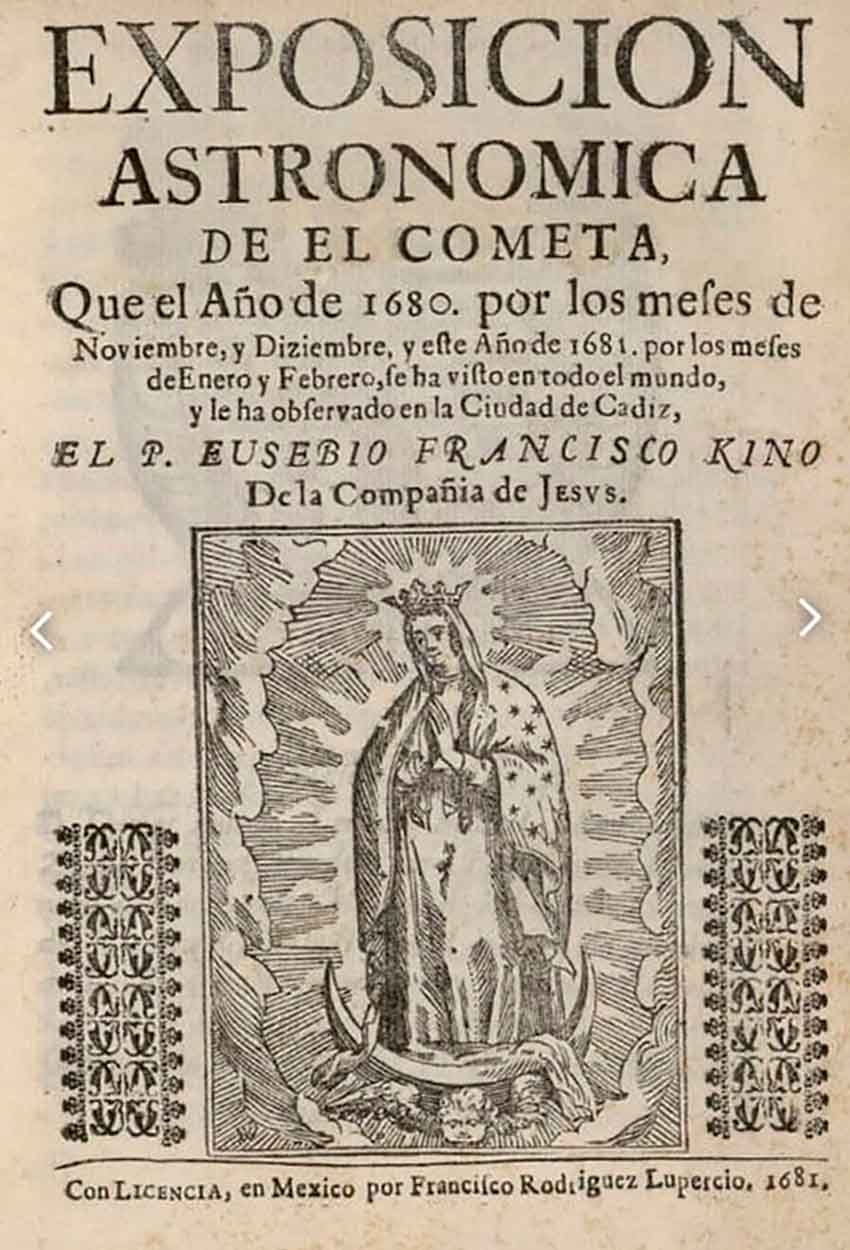

So, as an obedient Jesuit, off he went to Mexico. He somehow missed his ship in Spain, however, and while waiting for the next one (a full year), he dedicated his time to charting the course of what was then called the Great Comet of 1680. It had a spectacularly long, beautiful tail that was so brilliant, people said it could be seen in the daytime.

The first thing Kino did upon arrival in Mexico was to publish his findings on the comet, one of the earliest scientific treatises published by a European in the New World. He was then given his first assignment, which was to lead an expedition to “the Island of California.”

From the outset, Kino suspected that what we now call Baja California was really a peninsula, not an island, but since none other than Englishman Sir Francis Drake had taken the position that it was an island, Spain had rejected Kino’s idea and insisted that it was an island.

Not just an island, mind you, but purportedly the biggest island in the world.

Kino was put in charge of the mission of San Bruno, located halfway up Baja California. It was a tough assignment. Just crossing the Sea of California (what the Spanish called the Gulf of California) often took five days, and the ships usually had to deal with very rough waters.

In addition, since the area around the mission was suffering from drought in those days, all food had to be shipped from the mainland to the mission. The situation was untenable.

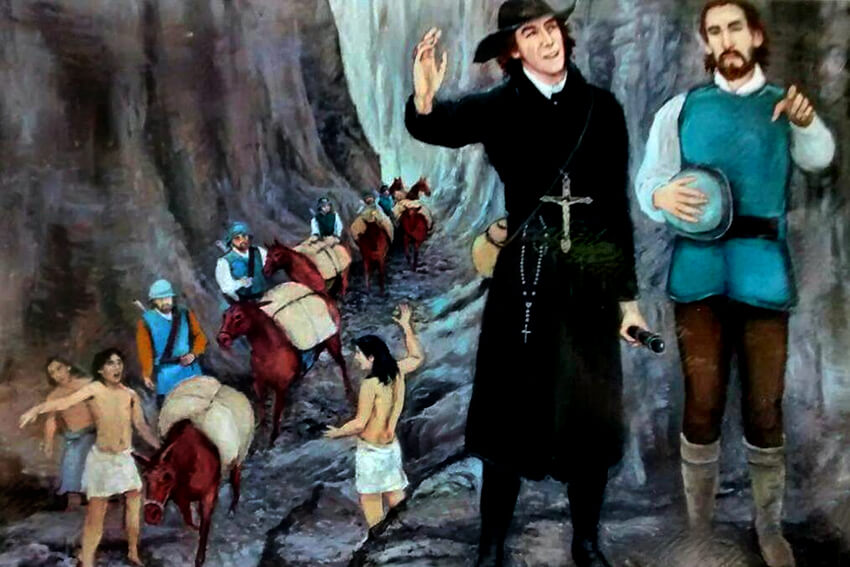

While he was at San Bruno, however, Kino somehow found time to lead the first crossing of Baja California to the shore of the Pacific, an arduous route through steep mountains — a route which Carlos Lazcano retraced 305 years later.

Forced to abandon the San Bruno mission because of the high cost of transporting everything by boat, Kino was afraid he would end up teaching in Mexico City, but his superiors surprised him by announcing that he was being sent far to the north, to the most remote Spanish outpost of all, located at the northern edge of the Sonoran Desert, in what is today Arizona.

It sat a distance of almost 2,500 kilometers away from Mexico City.

Padre Kino had now been in the New World long enough to realize that the Jesuits’ plans to convert the natives and teach them trades were being stymied by the practices of the mine owners in New Spain. The missionaries would bring their converts to the settlements for instruction, whereupon the Spaniards would seize them and force them to work in the mines without pay.

It didn’t take the local indigenous people long to figure out that becoming a Christian meant becoming a slave.

This was the subject Kino mulled over during the month that it took him to travel from Mexico City to Guadalajara, where he planned to present his complaint against slavery to the Royal Audiencia.

On December 16, 1686, Kino stood before the high court of justice to state his case and was told, “A royal order dealing with this very matter has just arrived from Spain. The king and queen have received complaints on this subject and wish it to be known throughout all the New World that no Indian shall be obliged to serve in the mines or work in any manner without pay for 20 years after baptism. Here is a copy of that order. You may take it with you.”

Although the royal decree protected baptized Christians from slavery (for a while), Kino was dead set against the enslavement of anyone at all and fought against it his entire life.

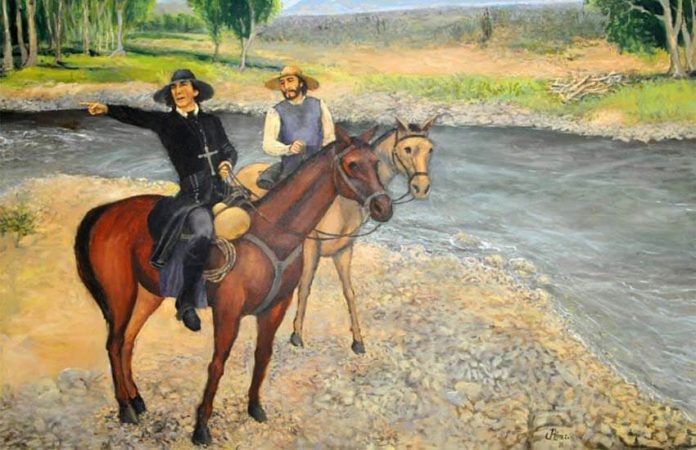

In 1687, Kino reached Cucurpe, which at the time was the farthest outpost of New Spain. “Beyond this point,” people told him, “are the Pimas — a warlike, troublesome people.”

Here follows a period of years during which Padre Kino travels everywhere among the Tohono O’odham people, called — in the grand old style of the Spaniards — “Pimas.” According to Kino, they were “friendly, cooperative and pacific.”

Such warm relations developed between the Pimas and Padre Kino that even today, old-timers speak fondly of him as if they had actually known the “black robe” himself.

Over the years, Padre Kino traveled to settlement after settlement, creating a harmonious society despite the frequent attempts to wreak havoc by certain bloodthirsty military leaders.

One of these was Captain D. Antonio Solís, whose misdeeds were so notorious that he was eventually decommissioned and sent back to Mexico City. There, Solís took advantage of his situation to spread the worst sort of tales about what was going on in La Pimería Alta (Northern Pima Territory).

When Kino heard rumors of Solis’ machinations, his response was to sit down and write a book. The recent history of La Pimería Alta went into the book, together with the geography. Naturally, he accompanied all this with an incredibly detailed map of the area.

Once he finished his book, Kino selected several young Tohono O’odham men to accompany him (so that the Spanish authorities could judge for themselves just what these Pimas were like) and rode all 2,500 kilometers to Mexico City to defend his people.

This resulted in a long peaceful period in the area. At last, Kino — though his health was failing — could concentrate on the subject that had been in his heart ever since his arrival in the New World: California!

He had always regretted having to abandon his “children” at the mission of San Bruno and had always hoped that Baja California would turn out to be a peninsula, providing an overland route by which he could bring food and supplies to the people he had first worked with.

Then, in 1698, Padre Kino learned that the mission in Baja California had been reestablished and that the Indians had not forgotten him, but he was told that the costs of supplying the mission by boat were as outrageous as ever.

“I paid a fortune to ship 20 cattle from Mexico City to California!” wrote his friend Padre Salvatierra.

Kino, who was suffering from chills when he read this, forced himself to stand up and, with a blanket wrapped around his shoulders, staggered to the door and called his young Pima foreman, Marcos.

“We are mounting an expedition,” Kino told him. “We will follow the Gila River west until we reach the sea.”

For the next five years, Kino fought off fevers and explored and mapped the mountains and desert to the west. In 1702, he summed up his findings: twice he had seen the head of the Gulf of California from the tops of high mountains near what is now the Pinacate Biosphere Reserve.

Convinced that he had solid proof that Baja California was a peninsula, Padre Kino returned to his mission among the Pima people until his death in 1711.

Kino’s many expeditions on horseback had covered over 130,000 square kilometers, and he mapped an area 320 kilometers long by 400 kilometers wide. For more than 150 years after his death, his were the most accurate maps of the area. Kino also gave the Colorado River its name.

Baja California is, of course, a peninsula, and today there is a highway running down its entire length. Ironically, Carlos Lazcano reports that the native people living in the area of the San Bruno mission “are today just as poor and marginalized as they were back in the 1680s.”

The poor people of Baja California finally got their road, but, unfortunately, they no longer have Padre Kino to come to their aid.

• Kino en California. Textos, cartografías y testimonios 1683–1711 by Carlos Lazcano Sahagún and Gabriel Gómez Padilla is written in Spanish, has 1,357 pages and was published by ITESO in 2021. A print version is available from ITESO and an e-book version on Amazon.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.