Tour guide Fernando Fuentes is a bottomless well of information.

We are walking through the Roma Sur neighborhood in Mexico City, which happens to be where I live, and he is rambling off a string of names that link Mexico’s most famous president, Benito Juárez, to the architect who built the school across from us on the sidewalk. I’m not sure if I totally follow, it having to do with the president’s personal secretary, who became his son-in-law and then someone’s grandchildren. And somewhere along the way, someone was Cuban.

“I can talk to you about Colonia Buenos Aires or some other place, and you might be interested about one thing or another,” he tells me right off the bat, “but you’ll always care more when we’re talking about your own neighborhood.”

Maybe that’s also true of the guide.

Fuentes has lived in this part of the city his entire 75-plus years, and while he was born one neighborhood over from Roma Sur — in Colonia Hipódromo — he has mountains of knowledge about the entire Roma-Condesa territory that combines the five neighborhoods of Roma Norte, Roma Sur, Condesa, Hipódromo, and Hipódromo-Condesa. This part of the city was developed around the turn of the century, one of Mexico City’s first suburban areas, and has become famous for its Art Deco architecture, tree-lined parks, quaint streets — and these days — upscale eateries and hip boutiques.

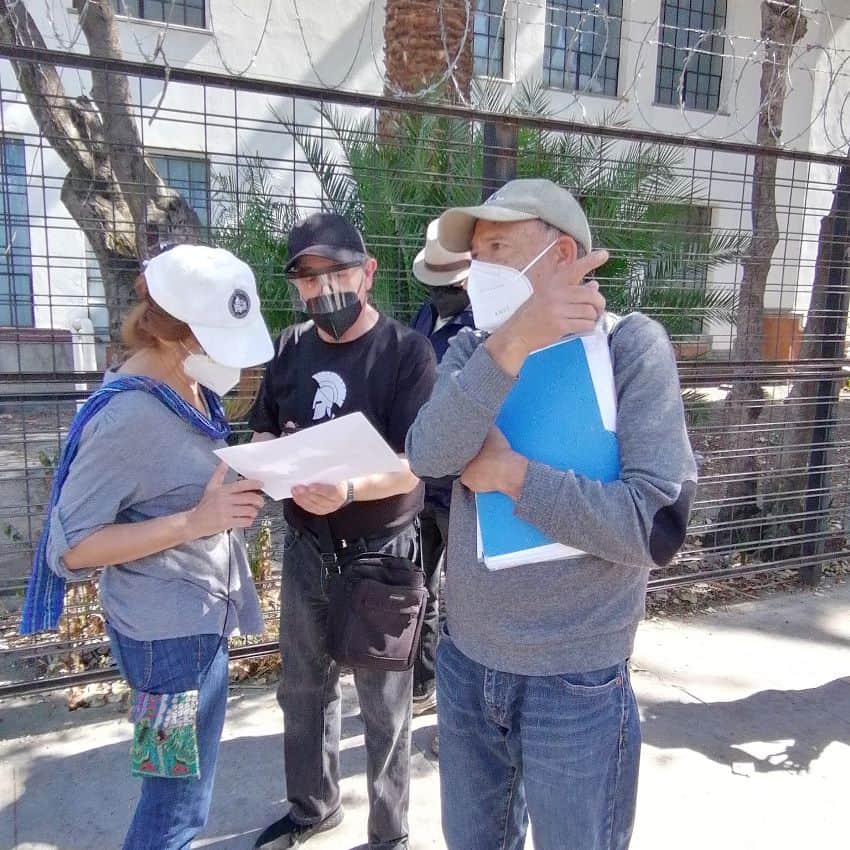

I met Fuentes a few Saturdays ago when, in the midst of quarantine, I was itching to get out of the house and joined his mask-covered, socially distanced tour around my neighborhood.

He’s been offering tours — for free — for the past 57 years to anyone who digs local lore and history and is willing to listen to the extensive litany of facts and names that pour out of him once he starts to talk about the area’s contemporary history. When he was young, he did joint historical tours with some of the neighborhood’s old-timers. Now he’s the old-timer.

Even after writing my guidebook, Mexico City Streets: La Roma, I will admit to a continuing obsession with the neighborhood, and I am always fact-checking myself against longtime locals. I confess to going on the tour partly for that reason. I found that while he confirmed a lot of what I knew, there were other things that were new: like the fact that the Benito Juárez school we were sitting in front of had a mural painted by one of the country’s first muralists, Roberto Montenegro, and that it is quite possibly the largest primary school in the country.

With all neighborhood history, a little skepticism goes a long way. Fuentes is quick to caveat word-of-mouth info with a “so they tell me …” And while I found myself annoyed by the other neighbors on the tour that butted in to tell their own stories, he told me that he loves that part — that on every tour he learns something he didn’t know before.

This is a man who has also spent hour after hour researching the 488 blocks that make up the Roma-Condesa. As he tells it, his story began on the corner of Loreto and Amsterdam at the house of a midwife aunt where his parents went (instead of the hospital) the night he was born. He was born in the neighborhood and has never left.

Life for him as a youngster revolved around the Parque México — the heart of the Hipódromo neighborhood — and one of the area’s most beloved parks today.

“Other than my family, the people I cared most about were my friends in the park,” he tells me.

He spent his days playing U.S.-style football and generally causing havoc in the ʼhood, with an ear to the ground for stories and history.

His father, a photographer, encouraged him at a young age to investigate the origins of the neighborhood’s history, prompting him with questions like “If all the streets in Roma and Hipódromo are named after Mexican cities and states, why is Amsterdam street named Amsterdam?” (His best guess: it was named the same year as the Amsterdam 1928 Olympics.)

When he was still in high school, Fuentes started collecting old neighborhood photos and started putting together what he calls monographs. These are a handful of sleeves of paper printed with black-and-white photos along with lists of street names and their significance, as well as the oldest houses still standing and short histories of the neighborhood. He used to carry these in a backpack and hand them out to passing strangers or neighbors he thought needed a lesson in local history. There is nothing that irks him more than when someone says Parque México is in Condesa and not Hipódromo, for instance.

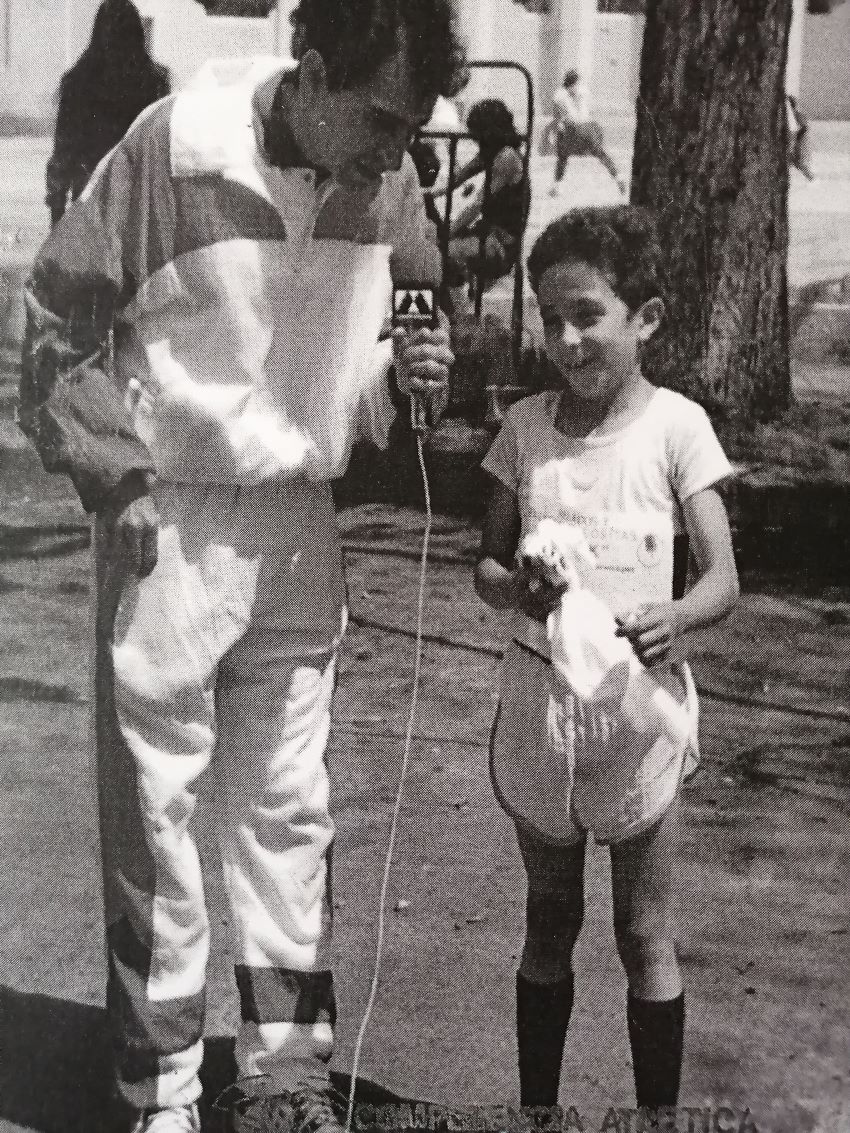

He shows me his most recent monograph for his Hipódromo tour: random photos of the original racetrack built there and the old social security hospital are interspersed with photos of his expansive family (eight siblings), looking serious but stylish in the park. There is even one of him looking stern in his baby high-waisted pants and tiny sweater.

He points out several buildings in photos and tries to explain to me what I am looking at. I know the neighborhood well and even give my own tours, but the city looks so impossibly different than it did 50 years ago; it’s like looking at Mars. That’s why he gives the tours.

“So that I don’t just give you the information [and] you have no idea what it is, we go for a walk and I explain when the school was built, who built it, what’s inside, etc.”

And there’s another reason why he does the tours. As his publicity leaflets so honestly announce, “I’ve been living in the neighborhood for 75 years, and I don’t have that much time left to tell people what I know.”

Also, his two grown children are completely uninterested in his archive. He’s afraid that they will just throw everything away when he dies, he tells us as a preamble to the tour.

“People always say to me, there’s nothing like a resident to tell you about their neighborhood,” he explains. “Other tour guides will give you general information, but a local gives you the details.”

When I ask him about writing a book, he shrugs off the idea; he doesn’t have the constitution for that kind of thing. It wasn’t until his ex-wife finally told him that he had to organize all his little scraps of paper that he even started getting serious about archiving the information.

Why not charge a little for tours, then, I ask. Surely they’re worth a small fee.

“In 1985, when the earthquake happened, I decided to put together a race for kids,” Fuentes tells me. “I organized that race for 35 years. We had categories starting from 1–2 years old to 13- and 14-year-olds. It was always free until the year 2000, but they raised the price on the trophies … So I decided I would charge 20 pesos, just to cover the costs. And after that it became a business. Suddenly we were charging, and for their 20 pesos, people expected bathrooms, bigger trophies, lots of things.”

When something is free, he says, you have zero expectations — which is not to say he won’t take a tip if you give him one.

To get in touch with Fernando Fuentes and take one of his great (Spanish-only) free tours, call 55 5264 4648. Since he’s never owned a cell phone, you will just have to catch him when he’s home and not out walking his favorite beat.

Lydia Carey is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily.