The sticky air is thick with the smell of chopped and charred agave plants at Palenque Don Goyo in San Baltazar Guelavila. Rain falls heavily on the rustic, family-run distillery that has been producing artisanal mezcal for 30 years. Droplets coat the leaves of 30,000 agave plants spread across this hidden valley in the Oaxaca hills.

The paved road connecting San Baltazar Guelavila to larger towns around Oaxaca city does not reach Palenque Don Goyo. The only route is a muddy track laden with footprints of horses, donkeys and goats.

“If the rain continues like this, it won’t be possible to drive back today,” Rodrigo Martinez Mendez, grandson and heir to the family’s mezcal business, tells us as he unlocks two arched doors to a large barn-like building.

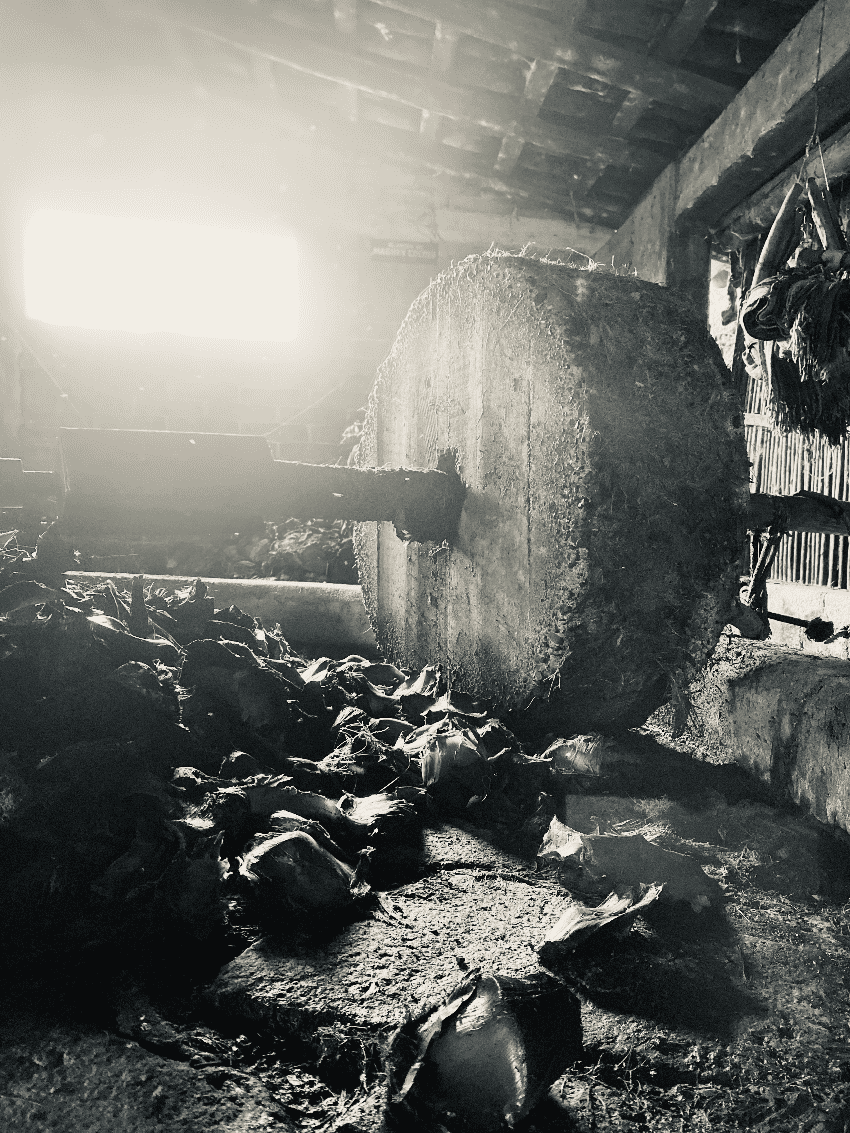

Gray hazy sunlight showers the remarkable contents of the space inside. Four huge wooden vats, or ‘tinas,’ with a capacity of 1,200 liters cast huge shadows across wooden walls. In the darkest depths sits a large circular wooden mill or ‘tahona’ which resembles a clock face the size of London’s Big Ben, but built into the stone floor. With three bottles in hand, Rodrigo jokingly remarks:

“At least we won’t run out of things to drink.”

The wild landscapes surrounding Palenque Don Goyo befit the type of mezcal made here.

The Mexican spirit is produced as an artisanal distillation, meaning each step of production is carried out by hand under the supervision of a maestro mezcalero, and more importantly, without machinery. Agave plants – once ripe, chopped up and roasted – are crushed by a horse-drawn wheel prior to fermentation and distillation.

Under the palenque’s flagship brand, Revelador, four different types of agave varieties, espadín, tepeztate, tobalá and cuixe, are made into mezcal, but only the maestro Gregorio Martinez Garcia and his close family know the specifics. The recipe remains a secret.

Today is a quieter day at the palenque, but Juan Martinez Garcia, the oldest member of the family and father of maestro Gregorio, is working the fields. He’s now 89, but his grandson Rodrigo tells me he starts promptly every day at 7 a.m. He’s hard of hearing, walks with a cane and breathes heavily. The sparkle in his eye when he introduces himself however, is as youthful as ever.

The family has had a busy month. Six hundred liters were made and then packed on pallets destined for New York in July. The batch constitutes their first-ever order from the United States, where the market for mezcal is booming.

Standing amongst endless rows of agave plants, we watch and listen as three generations of mezcal producers discuss the next commercial order in their native Zapotec language.

Much like the recipes for the artisanal mezcal produced here, the Zapotec language has been passed on through generations. The language, in which all three men learned about mezcal as young boys, faces possible extinction. Rodrigo, the youngest member of the family, tells us, “Whenever I am home with the family, we speak and work in Zapotec. But other than that, I don’t use it.”

As migration and travel become more possible and technological processes advance, there is a risk that Indigenous languages and artisanal processes will die with the older generations. Efforts are being made to keep them alive, but a cloud of uncertainty looms.

These traditional processes are some of the most-loved and admired aspects of life here, but whether they will become a remnant of times past is still to be determined.