I get it. If your Spanish was “all that,” you would be learning about Mexico through local sources.

But what if I told you that there is at least one Mexican publication that makes quality information available in well-translated English?

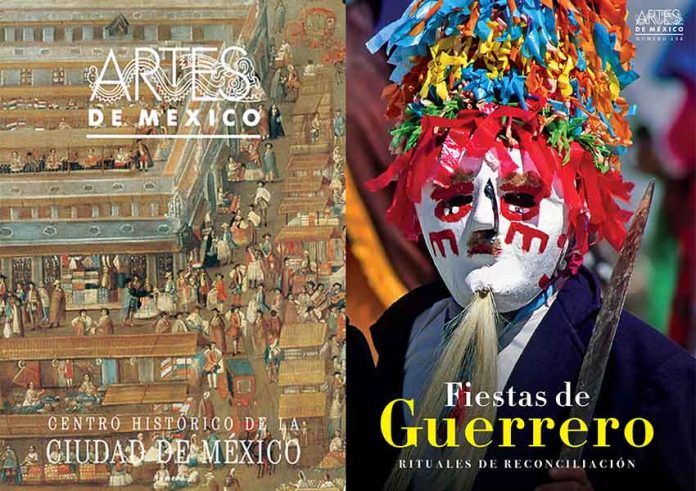

That would be Artes de México.

In 1988, Alberto Ruy Sánchez and Margarita de Orellana were a young couple looking for a career. The economic crises of the 1980s had not been kind to them. Despite doctorates and foreign work experience, they had to get by with various freelance and other academic gigs.

Then they found “their reason for living.” They were tasked with reviving a publication that had run from 1955 to 1980.

Published quarterly, Artes de México is neither a magazine nor a book but a hybrid. To distinguish it as such, let’s use the Spanish word revista.

Artes de México recruits experts and other noted writers to write interrelated articles within the issue to provide laypeople with an in-depth look at a thematic topic. Issues remain available as reference works years after publication.

The English language has been important to the publication since its relaunch. “Intuitively, we realized that we had a market [for this type of publication] in the United States because of the number of Mexicans living there,” says De Orellana.

But foreign mass distribution there has not worked out. The English today serves to promote Mexican culture globally. But since it is not the organization’s main focus, translations are in the back, meaning you have to flip back and forth to read the English and look at the excellent photographs.

And despite being called “Arts of Mexico,” the publication actually covers a wide range of cultural topics, walking a middle road between pop culture and the academic. Issues have been dedicated to biodiversity, festivals, holidays, food, clothing, cultural symbols, indigenous cultures, history and, of course, the various arts. It presents information not readily available in other media.

One early issue, for example, focused on legendary cameraman Gabriel Figueroa, who worked on over 200 films during Mexico’s golden age of cinema. He was all but forgotten by the late 1980s. It is fair to say that that issue’s publication helped save Figueroa and his work from oblivion.

De Orellana is proud of the work they have done on topics related to Mexico’s indigenous peoples, saying that other media tend to push politics and propaganda, “… often without knowing the roots of the topic.”

Octavio Murillo, head archivist for the National Institute for Indigenous Peoples, agrees that the revistas have been important in bringing knowledge about indigenous communities to a wider audience, pointing specifically to issues they did that were related to the Huichol people and pre-Hispanic art.

Certain topic categories have been particularly successful, such as food. There are issues dedicated to the chili pepper, the nopal cactus, tequila, mezcal or pulque. Several have been devoted to chocolate and corn.

The dietary habits of Mesoamerica have been extensively examined. There are also two issues called Seeds of Identity (Semillas de Identidad) highlighting the foods from Mexico that have impacted world cuisine.

Artes de México’s greatest success has been with the country’s handcrafts and folk art, despite some initial resistance by the publication to covering such work. Its first revista on this topic was on Puebla’s Talavera pottery, about which nothing had been published for decades.

De Orellana credits these issues’ popularity to the growing respect that Mexico’s artisans have earned both inside and outside the country.

Gayle Pierce, president of Los Amigos de Arte Popular, the largest Mexican folk art support organization, has supported Artes de México‘s work in this realm for many years. “[It] is a tremendous resource for someone new to the genre or the seasoned collector,” she says.

Artes de México has enjoyed longstanding relationships with education, government and cultural institutions. The revistas are important to both teachers and students, but not just in the humanities; graphic designers study them as well. The publication’s name appears regularly in bibliographies of academic works in both English and Spanish.

However, its future is cloudy.

The onset of commercial internet in the early 1990s has presented Artes de México with the same challenges as other publishers. It now competes with free and nearly unlimited information, with younger generations preferring video. Advertising, the staple of the publication’s original operations, is no longer feasible.

The revista still enjoys support from Mexico’s educated classes. The organization’s ties to traditional cultural and educational institutions mean that the physical publications remain central. But it also means losing touch with many readers under 30. This is a problem that Ruy Sánchez and de Orellana have not yet fully worked out. Artes de Mexico is a nonprofit and has shifted to collaboration with its main supporters in the production of revistas and more traditional books.

They have organized events related to Mexico’s culture, such as a recent forum to discuss a recent ban on rótulos in Mexico City. They have hired a more digitally savvy staff to explore ways to make better use of online tools. On their website, you can read selected articles from various issues, although those are only in Spanish.

But it is more difficult to pay the bills and get the kind of high-quality content still in demand into people’s hands when they are no longer willing to pay 300 pesos or more per issue for four issues per year.

For those of us who still like the idea of a “book” in our hands, there is no indication that Artes de México will abandon physical print anytime soon. Issues of the publication, present and past, are still readily available in many bookstores (including some of Mexico’s biggest bookseller chains), museum shops, book fairs and, of course, from their website.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.