In February, media outlets started blaring warnings about an impending “Day Zero” when Mexico City would run out of water. Lingering drought and extreme heat are conspiring to threaten the most populous city in North America with a disaster of epic proportions.

The ominous reports even provided a date on which more than 20 million people would be left without water: June 26. A crisis, yes, but Mexico City is not on the verge of a parched, gasping apocalypse… yet.

It’s true that the Mexico City Metropolitan Area (ZMVM) is desperate for water. Years of low rainfall have pushed an already strained delivery system to its limit. Record setting temperatures have worsened the situation.

Lost in most headlines, however, was the fact that Day Zero refers specifically to the Cutzamala system, which supplies about 28% of Mexico City’s water. To be clear, that system is facing a very real threat of becoming inoperable if action is not taken, or if a generous rainy season doesn’t blow into the valley.

While solutions are being formulated, this doesn’t mean the ZMVM is free and clear. Sixty percent of Mexico City’s water comes from an overexploited aquifer that is being depleted at twice its recharge rate and could run dry in 40 years. But the subject of Day Zero fears is the aging hydraulic system that pumps water vast distances uphill to 12 of Mexico City’s 16 boroughs and 16 neighboring municipalities.

What is the Cutzamala system?

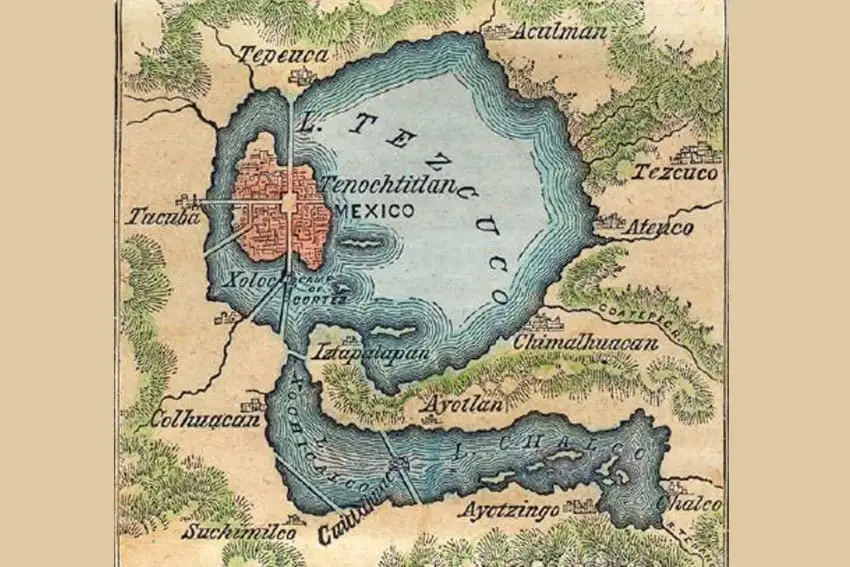

The Valley of Mexico is a highland plateau surrounded by mountains and volcanoes. Present-day Mexico City sits in this basin, once home to five interconnected lakes when the Spanish arrived in 1519, eventually conquering Tenochtitlán in 1521.

For four centuries, the lakes were drained for flood control, while wells and aquifers were used for drinking water. Early last century, scientists observed that the extraction was contributing to the city’s sinking up to 40 centimeters a year into the old lakebed of Lake Texcoco. The exploitation of aquifers within the city was banned and new wells were excavated on the city’s outskirts, but that was insufficient to quench the thirst of the rapidly growing metropolis.

In the 1940s, a system of aqueducts was built to bring water from the nearby Lerma River basin northwest of the capital, but problems arose when area residents protested the extraction of what they saw as their water. By the 1960s, the more distant Cutzamala River basin was seen as a solution and in 1976, the pipes, pumping stations and reservoirs of an existing México state hydroelectric system were turned over to the Cutzamala project, converting the works from energy generator to water provider.

The result was a complex inter-basin transfer relying on 11 dams, seven reservoirs, six pumping plants and 322 kilometers of canals, tunnels and pipelines that carry water from the Cutzamala basin up more than 1,100 meters in elevation difference through Michoacán, México state and Mexico City: the Cutzamala system we know today. Considered one of the most significant engineering works in all of Mexico, it provided nearly 15 cubic meters of water per second to meet the needs of the massive population in the Valley of Mexico.

The infrastructure has not aged well, and studies show that more than 40% of the water is lost through leaks. The system’s reservoirs are losing water due to extreme heat and drought is shrinking the rivers that feed it.

Fears of an impending Day Zero were fueled by reports that less than half of Mexico City residents were getting reliable water service, 30% were getting their water delivered by truck and the remaining 25% were stuck with a water-rationing system known as “tandeo” whereby the water taps only work during certain hours of the day.

Then came headlines about dwindling water supplies in the reservoirs. The Valle de Bravo and Villa Victoria reservoirs — the two biggest in the Cutzamala system — had shrunk to their lowest levels in 25 years and extraction was reduced by half. The entire Cutzamala system lost 6.22 million cubic meters of water in early April and was at a historically low 30% of capacity, within range of the limit at which the pumps would grind to a halt.

Taking steps to remedy the situation

Deeper wells are being dug and more residents are seeing water rationed. The system’s flow rate has been lowered and water pipe maintenance is being carried out, despite the inconvenience of shutting off water to neighborhoods for days on end.

Polymer tubing is being inserted into the existing water pipes to reduce leakage and a new aquifer discovered about 135 kilometers (84 miles) north of the Valley is being studied.

Additionally, researchers from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) presented a far-reaching proposal to address Mexico City’s water crisis. The project includes intensive water capture and artificially recharging the aquifer by injecting surface water directly into the ground. It encourages the use of treated residual waters in agriculture, as only 75% of irrigated lands in the Valley use treated water and less than 12% of that water is reused. The project is estimated to cost 97 billion pesos.

While these are positive steps, increased water rationing is inevitable in the foreseeable future and additional strategies must be found to avoid a real Day Zero scare. Either that or consider renewing sacrifices to Tlaloc, the Mexica god of rain.

Tom Buckley writes for Mexico News Daily.