I first heard about the so-called “Killer Granny” from the woman who helps me with housework.

“It’s all over the news!” she said.

She seemed ambivalently excited about it. On the one hand, it’s awful for people to die violent deaths. On the other hand, well, when authorities won’t enforce an already difficult-to-enforce law, what options are there for you to get justice?

I made a mental note to read about it later but forgot: my memory is basically a fishnet bag, much too easy for things to fall out of. I didn’t have to remember, though, because I soon saw Mexico News Daily’s own article about it.

I immediately thought of the United States’ own most recent “folk hero” killer. Luigi Mangione, of course, is now known far and wide for having killed United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson.

To many, this was a justified, if unsavory, act, and many hailed Mangione as a hero. Bankruptcy, continued suffering and death are common results of U.S. insurance companies refusing to cover medically necessary care. Most people know at least someone — in many cases, lots of people — who’ve suffered greatly because their insurance provider refused to cover needed care.

So, yes. Ask people in the U.S. if they think murder is wrong, and you’ll get a resounding “absolutely!” Ask people if murder is wrong in very specific circumstances, and you’ll get some more nuanced answers. Killing someone who’s done nothing to you — bad. Killing someone whom you know the justice system will never touch might be a different story.

Mexicans, it turns out, feel the same way by and large.

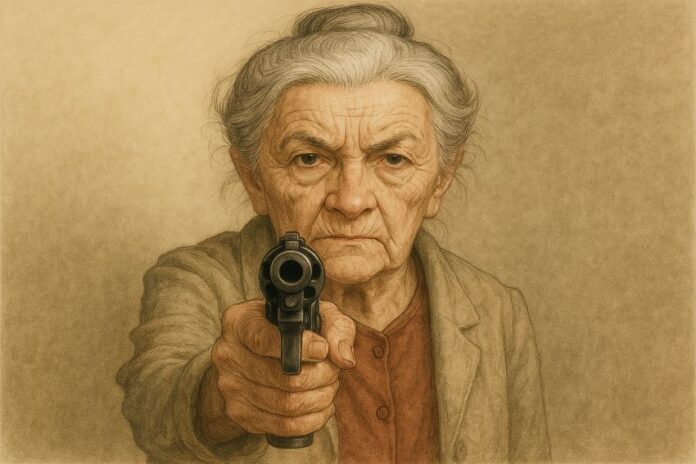

Only, the person in question here is an older woman wielding a gun. In case you haven’t read the article, here’s the gist of it:

A woman named Carlota — whose adult daughter, Mariana N., is the owner of what Mariana claimed was an illegally occupied property — arrived with a pistol at said property with Mariana as well as with Mariana’s brother, also an adult, who is seen in videos also holding a pistol.

What was caught on a security camera was Carlota confronting the occupants on the home’s lawn with her two children. She then shot three people: a 19-year-old who died instantly, a 51-year-old who died later at a hospital and a teenage survivor who was hospitalized.

There are still quite a few unanswered questions in this case. For example, did the alleged squatters know they were squatters? They allegedly claimed to have had a rental agreement, though they couldn’t produce it in time for Carlota’s satisfaction. This is understandable: I doubt anyone would have the presence of mind to think of solutions with a gun in their face.

Other questions: Had someone rented the house to them without the occupants knowing it wasn’t theirs to rent? Also: Carlota’s daughter Mariana N. had gone to México state authorities without any resolution, but how long did Mariana wait without action by authorities before turning to her mother for a solution?

And how did Carlota have a pistol? Remember, guns are incredibly difficult for private citizens to own legally in Mexico.

For many, the answers to these questions were either assumed or considered unimportant. This sociological wisdom is something that’s rung true for me every time, and this case is no exception: If something is believed to be real, then it is real in its consequences.

As I looked through video after video on the subject, I kept an eye on the comments. Here’s a typical sampling:

“It’s impotence that moves people to these extremes.”

“What’s really sad is having to take justice into one’s own hands.”

“It’s just that we’re sick of these kinds of people who invade property, and of the authorities who pay no mind to these cases.”

“I know people whose property’s been invaded for more than 20 years, and they still can’t get them out!”

“That woman showed us how justice should be carried out in these times… If the authorities ignore our complaints, then they’re basically gifting us the power of taking justice into our own hands.”

And on and on and on. Clearly, many people felt that the violence in this case was justified.

How big of a problem is squatting in Mexico?

Actually, it’s pretty significant. I personally know people who’ve had their property stolen; it’s not always by squatters. Plenty of cases have involved rich developers swiping land plots and paying off authorities too. I say this mostly because I want to take away the perception that this is only something perpetrated by poor people.

That said, the law is most definitely not on the side of owners. Once someone else takes hold of your property, it’s not easy to get rid of them. At all. To do so is a long, complicated and expensive process. And even so, anyone who’s lived in Mexico long enough knows how the law here both does and doesn’t work.

This is because citizens’ right to “dignified housing” is protected by the Mexican constitution. Try kicking someone out of dignified housing — even if their name isn’t on the deed — and you could run into trouble. To bypass the law, some owners try other means of “smoking out” squatters.

This might include cutting off water to the house or even sending extrajudicial thugs to oust them. If they can prove you did that, though, then they become the victims before the law, not you.

So that’s the context of this incident: if Carlota is to be believed, squatters took over her daughter’s home. Knowing she’d not easily be able to get them out, she “ousted” them herself.

And judging from the public response, quite a lot of people are familiar with — and are mad about — this very common form of injustice. They’re holding Carlota up like many in the U.S. held up Mangione.

What will happen in this case? Time will tell. But chances are, Carlota’s new permanent home will be a jail cell, her plan having backfired spectacularly.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.