Sometimes when reading about current events I have the sensation that we’ve been erroneously sucked into some horrible dimension where nothing works the way it’s supposed to and everything is just terrible.

The general humanitarian crisis of millions of people around the world doing whatever they can to escape unlivable homelands for unwelcoming new ones is among the things that most produces this feeling.

Migrant caravans with participants numbering in the thousands have been making their way up and across Mexico toward the United States, only to get backed up at ports of entry or tossed back over the border to “wait their turn,” as if Mexico were an independently-run waiting room.

Those “turns” can take months to come up, as it’s obvious that the U.S. policy for now is to discourage them from applying in the first place (by law it is their right to do so). It’s not fair to Mexico, and it’s not fair to the migrants, though you could argue that the moving pieces, though in most ways powerless, are the ones that most have agency in the situation.

That said, they’re doing what any one of us would do. We want to live in peace, we want our families to live in peace, and we especially want our children to at least have a chance at success and happiness.

But what’s in the rule book here? What do people only slightly better off owe to the desperate, especially when they weren’t the ones to decide to let them through their lives and communities?

All in all, though, there has been some grumbling, Mexicans have been good sports and seem to be doing their best to be generous and hospitable, as these are fairly well-cemented cultural characteristics.

But everyone has their limits, and reports suggest that resentment among the hardest hit (those in tiny towns along the southern border and those in big cities along the northern border) is starting to build, not to mention a growing panic about how they will sustain continuing waves of people (especially considering the added economic hardship caused by long delays at the border, a topic for another column).

So far there’s no end in sight, and many are suffering from “migrant fatigue;” travelers are disrupting the fabric of an already-stressed society, not for the purpose of disruption, but out of desperation.

Central American migrants have rightly determined that there is safety in numbers, and in traveling with others are helping to protect themselves from criminals that could easily take advantage of poor foreigners in a place where they don’t know anyone and wouldn’t be missed.

The flip side of that coin, however, is that it becomes much easier for their hosts to see a gigantic mass of people as a herd of invaders rather than individuals in need of help. Add to that terms like “catch and release,” which sound like something one does for fish or animals — soulless pests that swarm and need to be brought under control — and we have a good part of the list of requirements for justifying atrocities against an entire population.

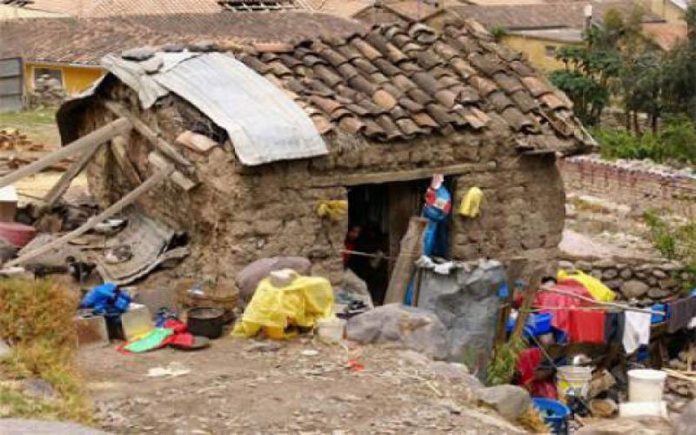

Surely they understand the hostility with which they’ll be met in the U.S. and — increasingly — in Mexico. How bad is the suffering where they live that they prefer literally anything else to staying in their homes? Or could they simply be unable to imagine the problems that await, assuming that they can’t be as bad as what they’re running from anyway?

It seems that the more hostile U.S. President Trump becomes, the more they set out in bigger and bigger groups, daring him to escalate, daring the Americas as a whole to take some sort of drastic action. The back-and-forth by Mexican President López Obrador hasn’t helped matters, promising fast humanitarian work visas initially, then backing off when the sheer number of applicants and new arrivals became overwhelming.

Generosity in Mexico paired with the country taking on the responsibility of keeping migrants out of the U.S. is turning out to be more than the country can handle.

López Obrador has been criticized for “bowing” to Trump, but I think treading lightly around a confirmed bully that no one has been able to beat and could cause even more harm than he has already is not bad policy.It’s not great policy either, but this is the dimension we seem to have been sucked into.

All of this drama is taking place in the political, economic and moral spaces of Mexico and the United States. Many look to Canada as an exemplary model of open doors to immigrants, but all emotions aside, it’s a country that doesn’t have a thousands-mile-long gate that swings back and forth between it and all of Latin America.

It has served, however, as a model for answering these questions by its treatment of other refugees: what responsibility do we have to accommodate people who fear for their lives and find themselves obliged to make a space for themselves somewhere else?

How do we peacefully make room? Could the U.S. make space for so many? (Certainly.) Could Mexico? If we did, would most of the rest of entire country populations follow? In all of the Americas, we have serious problems with inequality. Would the arrival of so many new people improve or exacerbate the situation?

Humans migrate. It’s what we do, and it’s what we’ve always done. Except for the indigenous (and even them if you go far enough back in history, I suppose), all of us here in the Americas are the descendants of migrants or are migrants ourselves: some willing, and some unwilling. But now there are seven billion of us miracles on this earth, and dwindling resources, so what to do?

Our best bet, but one that I see as depressingly far-fetched, is to work as hard as we can to drastically improve conditions in the countries from which they are arriving.

So start pitching ideas, folks: how do we make other countries places where their people at least sense a sliver of hope?

Sarah DeVries writes from her home in Xalapa, Veracruz.