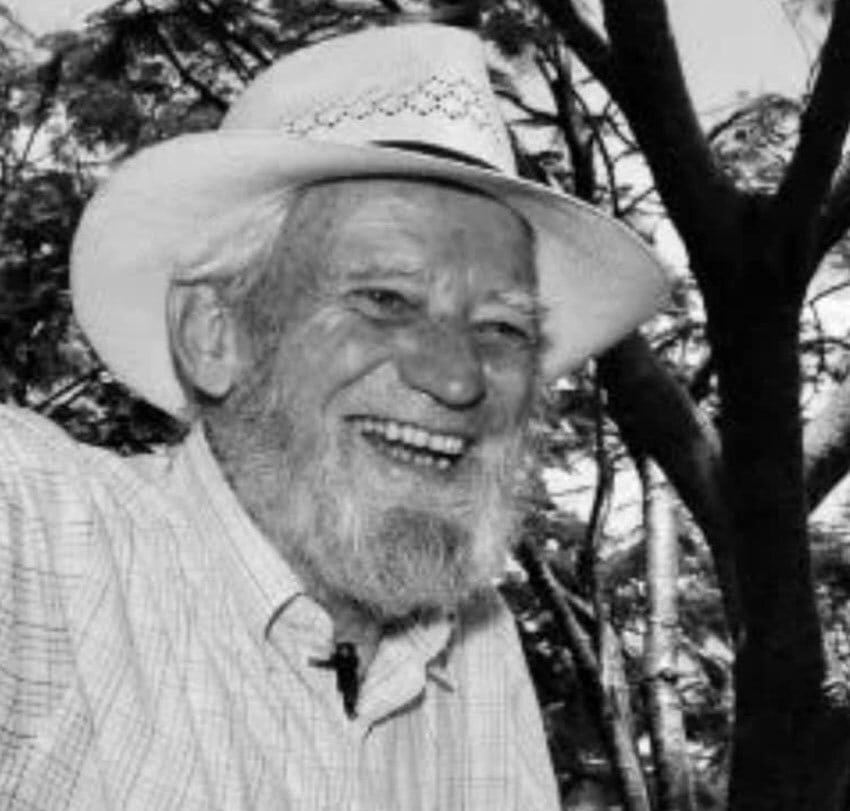

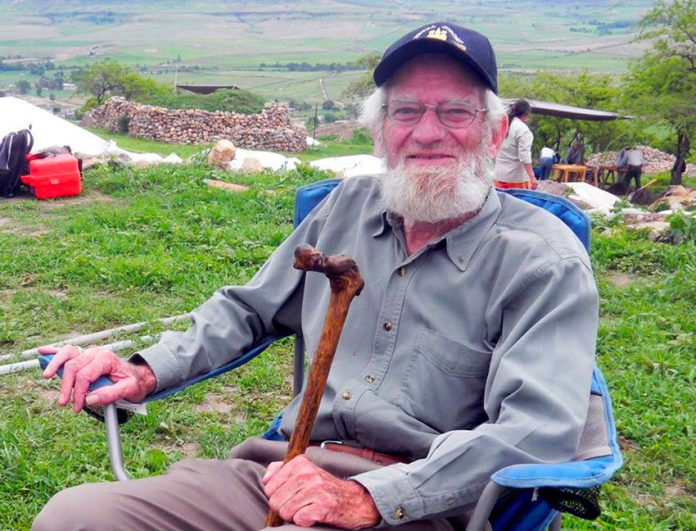

A pioneer in the archaeology of western Mexico, Otto George Schöndube Baumbach died on December 30 at the age of 84. Although his name might suggest that he was a foreigner, Schöndube was born in Guadalajara and grew up on a sugar cane plantation in Tamazula de Gordiano, Jalisco, where his father worked as an engineer in a sugar refinery.

Schöndube eventually attended the Institute of Sciences in Guadalajara and went on to study mechanical engineering at Mexico City’s Universidad Iberamericano, perhaps in an effort to follow in his father’s footsteps, but his heart was not in it. Beset by poor grades and vexing allergies, he left off studying for more than three years.

“My father said I was allergic to engineering,” he later wrote.

Downhearted, Schöndube wandered the streets of Mexico City. One day, inside the National Museum on Moneda Street, he discovered that the country had a school of anthropology. This brought back memories of his grandfather Rodolfo, who would show him figurines and pots he had found in his fields and recount exciting tales of archaeologists he had known, like the American anthropologist Isabel Kelly. Intrigued, Schöndube decided to switch careers and received his degree in 1962 at the National School of Anthropology and History.

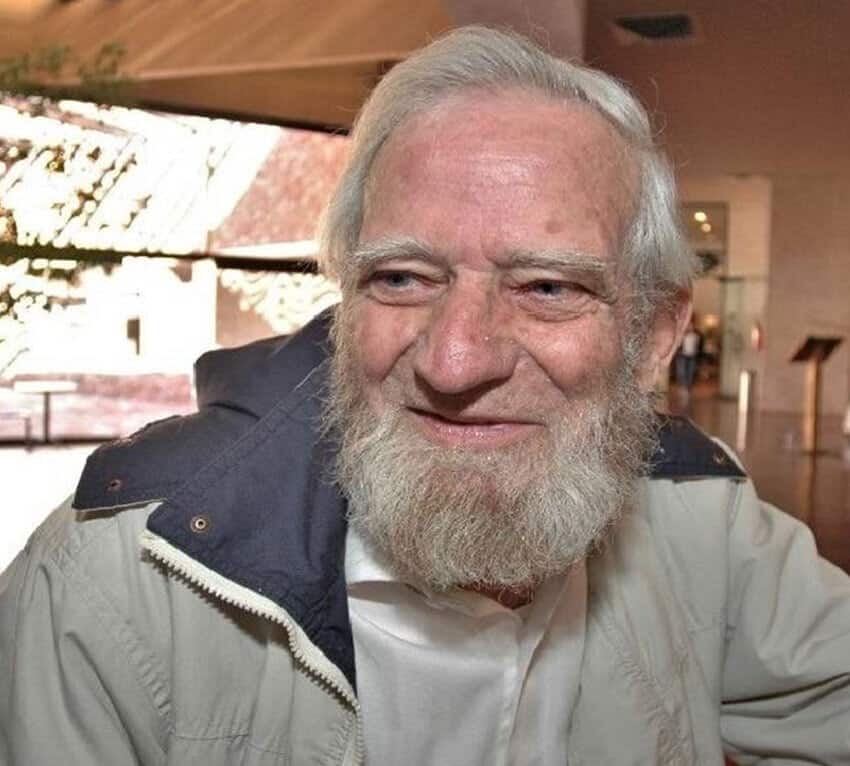

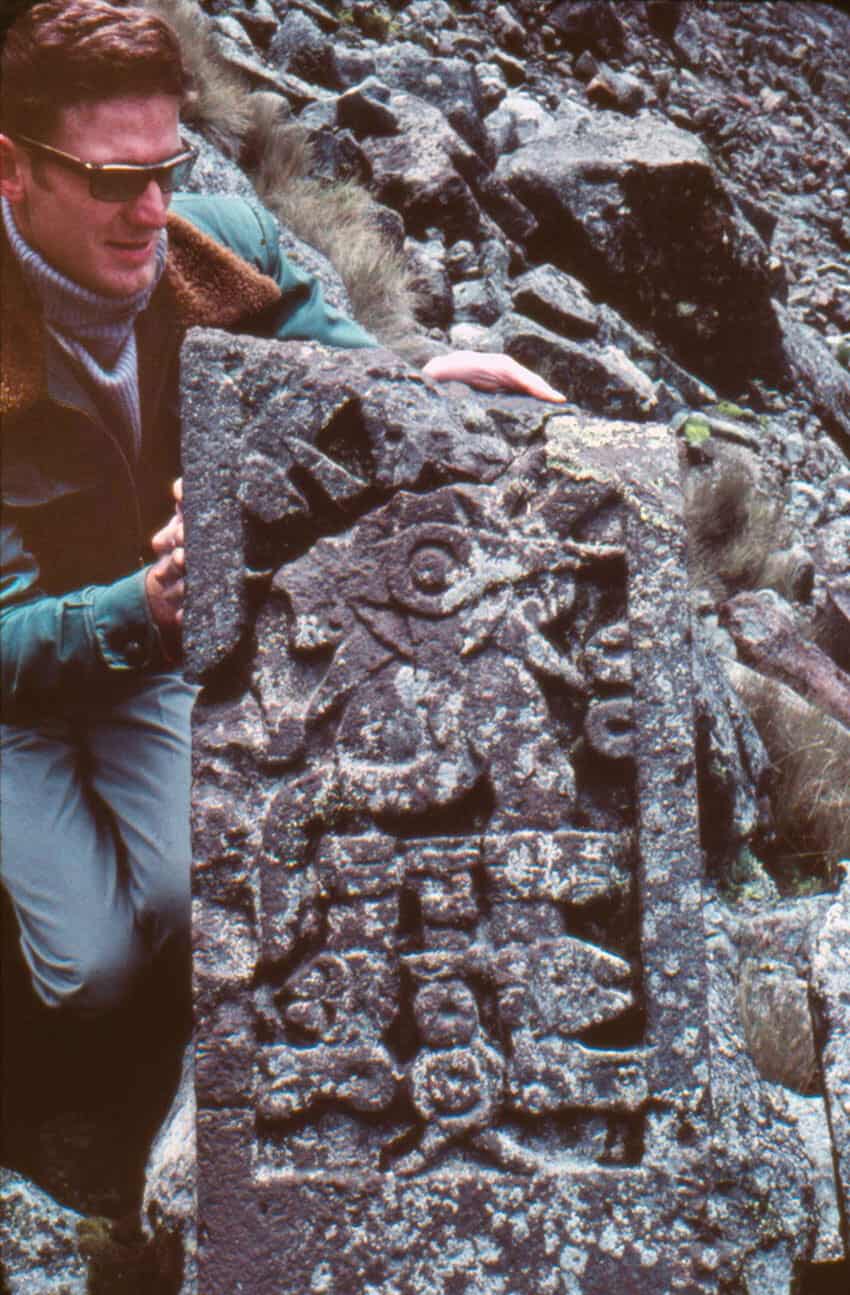

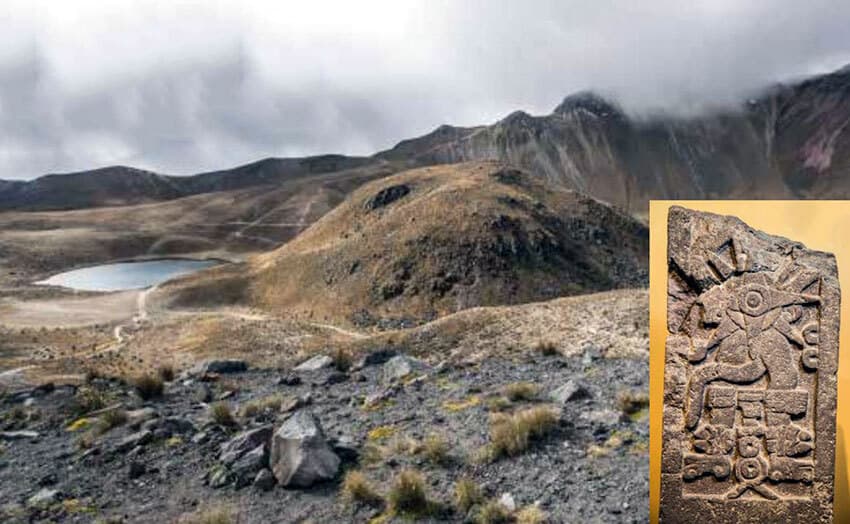

As an archaeologist, Schöndube worked all over Mexico, from Tlatelolco to the 1,500-year-old ruins of El Grillo within the confines of greater Guadalajara, and from the cenotes of Chichén Itzá to the peak of the Nevado de Toluca. It was there he discovered, lying out in the open, an ancient stele — a sculpted stone slab — dating back to 650 AD, which had been used for astronomical observation.

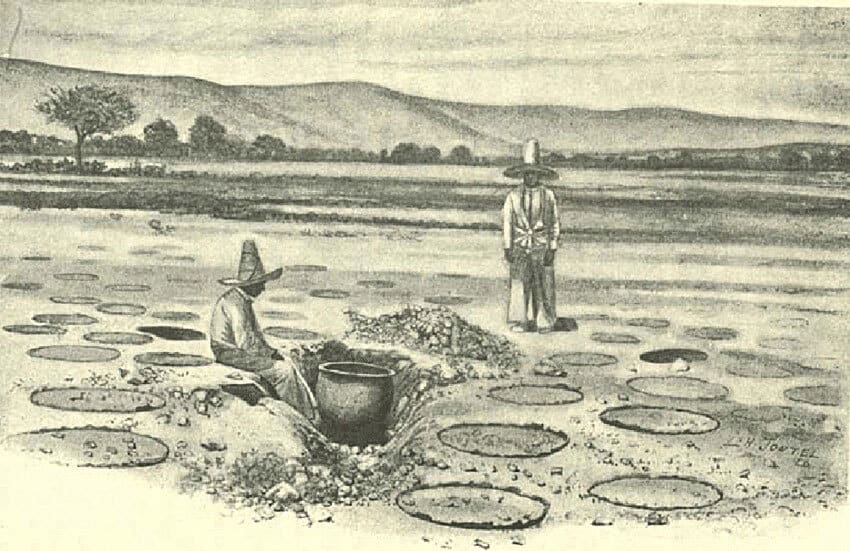

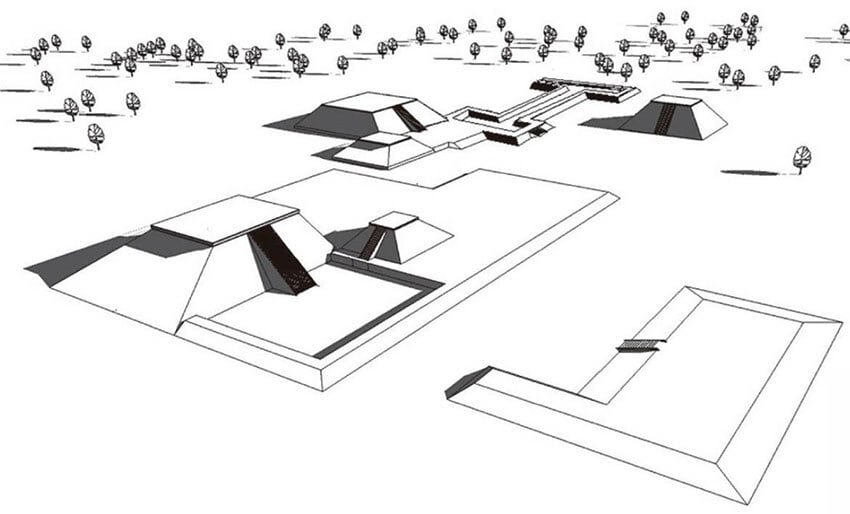

Eventually, he specialized in the pre-Hispanic cultures of western Mexico. A good example of his contributions and his way of working is the archaeological study of the Sayula Basin in Jalisco, for which Schöndube was the coordinator.

“We chose the Sayula Basin,” he wrote, “because it’s a graben with well-defined borders and because it’s not far from Guadalajara. Now, that doesn’t mean we didn’t end up busting our butts traipsing over every inch of it because those Sayula flats are nearly 50 kilometers long and four to five wide and we walked all of it. We wanted to see the development of human occupation of the region over long periods of time. Yes, we also studied satellite photos and air photos, but good archaeology is done on foot.”

The archaeologists not only walked the length of the basin but also did perpendicular transects “to observe everything we could see in every ecological niche.” This obliged them to climb from the salt flats all the way up to the adjoining highlands, typically towering hundreds of meters above them.

“We came upon ceramics, the foundations of ancient constructions,” said Schöndube, “evidence of the exploitation of the area’s resources, such as agricultural terraces, ancient salt works and the remains of old highways that actually crossed the lake. Our studies demonstrated palpable evidence of continuous human occupation from approximately 300 BC right up to the moment of the Spanish Conquest.”

Schöndube had to deal with INAH, the National Institute for Anthropology and History, which over many years of centralization and power politics had been accused of rigidity, of failure to protect Mexico’s patrimony and of corruption. He represented INAH at its very best: his frequent observations about good archaeology being done out in the field were in contrast to the opinions of some archaeologists who were quite content to do their work in the office.

It didn’t bother him that western Mexico has no Teotihuacán. He put his whole life into uncovering what he could find and documenting it.

“I like to defend the ancient cultures of west Mexico even though they don’t present us with grandiose monuments like those of the Mayans and Teotihuacanos,” he once said. “Bueno, nosotros somos de aquí, ¡qué chingados el DF! [After all, we’re from here, and to hell with Mexico City!] I’m concerned with what’s around me. Sure, it’s interesting to learn about the Mexicas and the Mayas, but how about what was going on right here? What is it that makes us different?”

That’s the spirit, Otto. And if there are any artifacts out there in the Great Beyond, I’m sure you are already busy digging them up.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years, and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.