Microdosing, using micro amounts of recreational drugs, often LSD or psilocybin, has reached Mexico, and one of its epicenters is San Miguel de Allende, a popular destination for American and Canadian expats living abroad.

“We had a client that had been on antidepressants for 30 years. When Covid started, she was super anxious, and then she started with the protocol,” says a psilocybin provider in San Miguel de Allende who asked that his name not be used because the drug is illegal in Mexico. “After one month, she picked up a paintbrush — she was a painter and hadn’t held a brush in her hands in five years. In a few months, she had 10 finished pieces. And there are so many stories like that.”

When asked why most people seek him out, he said older people are microdosing to prevent degenerative mental disease. “Some people just want to experiment with psilocybin in microdosing, and some people want to use it to deal with depression and moderate anxiety,” he says.

According to this provider, around two years ago there were murmurings of microdosing (using a tenth or twentieth of a typical recreational dose on a regular basis) in Mexico City. San Miguel clients began asking about acquiring the drugs locally.

He and his partner, after some extensive research, developed what they believe to be a balanced regime (called a protocol) that includes other legal fungi and some vitamins for maximum benefit. The results, he says, have been unbelievable.

Another client, with Lyme disease, says her brain fog has lifted, her depression is gone and even her tremors were reduced in just a few months.

Hard science behind psychedelics is historically patchy. There was excitement in the 1950s and 60s that these drugs might mean solutions to PTSD, depression and a whole range of mental illnesses.

While research sprung up all over the world, it was hindered by very public incidents like Timothy Leary’s Harvard study and reports that started to filter out to the general public about users’ bad trips, suicide attempts and psychotic episodes (even though, as Michael Pollan notes in his book How to Change Your Mind, “It is virtually impossible to die from an overdose of LSD or psilocybin, … and neither drug is addictive”).

By 1970, the U.S. government had categorized both LSD and psilocybin as Category 1 drugs. Scientific research on them became impossibly bogged down in bureaucracy and restrictions.

But studies and experiments with psychedelics never really went away, mind you. There were dozens of them (both academic and not) around the world that continued into the 1970s and 1980s, some even government supported and funded by grants — until money ran out and restrictions kicked in.

During that time, advocates and scientists explored psychedelics on the sidelines in a world that wasn’t quite ready to embrace them … yet.

In 2000, a Johns Hopkins University psychedelic research group was the first to get regulatory approval again in the U.S. to research them on healthy patients who had never used them before. Their 2006 psilocybin study got the world excited about researching these drugs again.

Author and longtime psychedelics advocate James Fadiman added the term microdosing into our daily lexicon. His 2011 book The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide, offers first-person reports of microdosing from a range of users.

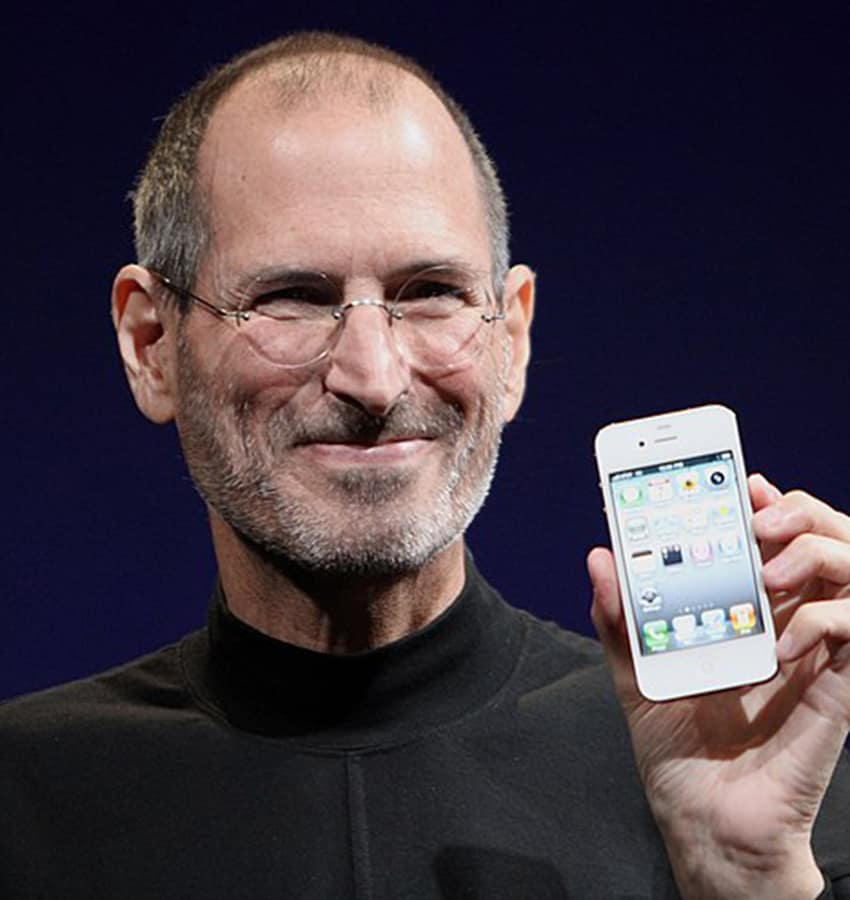

Instead of an ego-disintegrating trip, microdoses are said to provide daily benefits — clarity, creativity, an open mind, and open heart — without impairing your ability to function normally. This more mellow version of psychedelic use has been promoted in the past five years by Silicon Valley types looking to enhance their creativity and focus in the workplace.

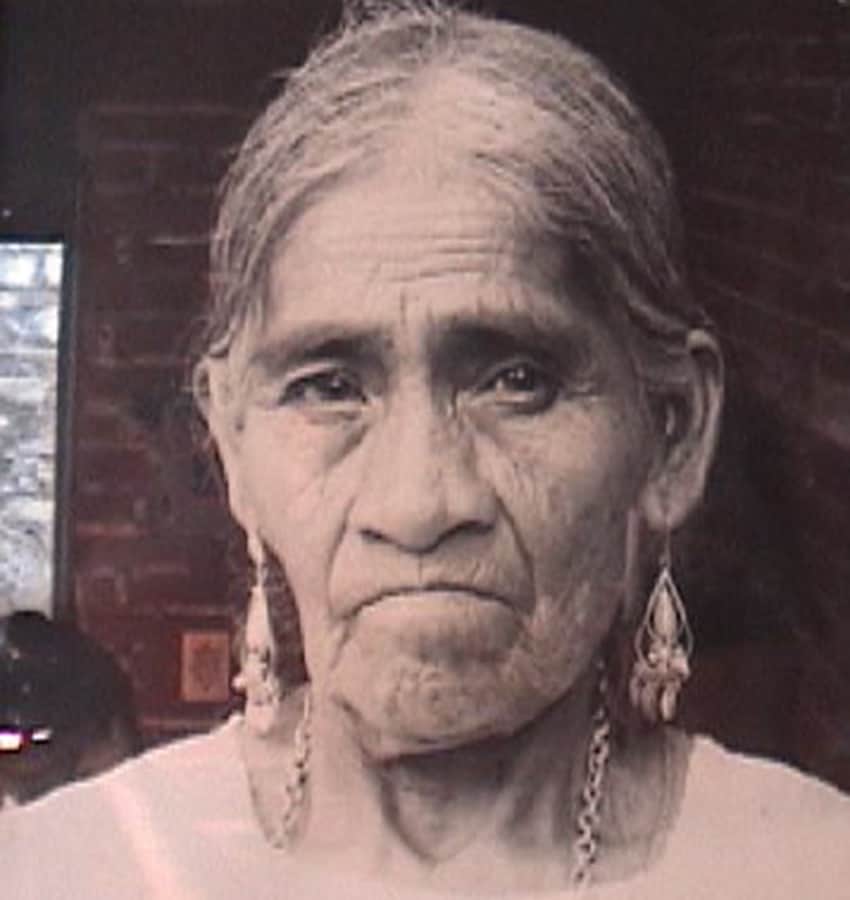

Mexico has a long history with hallucinogens used by pre-colonial indigenous cultures. In fact, the spark that ignited the psychedelic craze in U.S. and other nations in the 50s was lit in Huautla de Jiménez, a small town in Oaxaca

Writer Robert Gordon Wasson convinced a local curandera to let him participate in a traditional hallucinogenic mushroom ceremony. His 1957 Life magazine article introduced “magic mushrooms” to a larger audience.

But many I spoke to seem most interested in microdosing’s purported benefits for anxiety, depression and hopelessness — especially coming off a year and a half of isolation and pandemic chaos.

“I spent some years in the past on antidepressants,” says Ron Alexander, a retired writer now living in San Miguel. “I did Prozac and … I was really taken with it, but it kind of stopped working. A couple of years later … my doctor prescribed something else, and I did that for several years, and [then] it sort of stopped working … The depression didn’t really emerge again for me in a crippling way until Covid. ”

Alexander had researched how antidepressants diminish your frontal cortex and when a friend told him about microdosing, he believed psilocybin might be a more natural remedy.

“For me, the depression is putting a negative twist on too many things, catastrophizing things …” he says. “When I started microdosing, almost within days, all that lifted and I was happier. It had a bold impact.”

Other users are more interested in the possibility of opening and expanding consciousness and imbuing internal balance, as well as cultivating compassion.

Erika Haag, who has a regular yoga and meditation practice, was interested in what microdosing could do for her long-term emotional stability.

She and her husband had taken medicinal plants in larger doses and benefited a lot from the experience. “Once it helped us get through a really intense relationship crisis, and it’s allowed us to grow so much on so many different levels,” she says.

While Alexander’s approach to microdosing is more casual, Erika and her husband have followed stricter protocols.

Each protocol is a little different, with other substances to balance the psychedelic’s effects on the body. Haag says she enjoyed the experience but decided that microdosing was increasing her sensitivity too much and discontinued it after eight months.

“In theory, you are supposed to do it for one year, but right now I am trying to work without living by dogmas and instead listen to my body and what I need,” she says. “I felt really good stopping for now.”

For the hesitant microdoser, there is plenty of information online these days, including an entire Reddit subgroup. Both Fadiman’s and Pollan’s books have also spiked interest in this new form of self-medication. And as attitudes change about psychedelics, work to decriminalize psilocybin in both Mexico and the United States continues, with the hope that new research will find ways to use these drugs to benefit a larger population.

Like so many other ancient traditions, psychedelics may be a key to navigating life that the modern world is just starting to understand.

Lydia Carey is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily.